Red rail

| Red Rail | |

|---|---|

| |

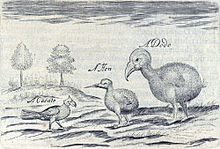

| Painting from the collection of Emperor Rudolph II in Prague, attributed to Jacob Hoefnagel, ca. 1600 | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Aphanapteryx Frauenfeld, 1868

|

| Species: | A. bonasia

|

| Binomial name | |

| Aphanapteryx bonasia (Selys, 1848)

| |

| |

| Former range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

| |

The Red Rail or Red Hen (Aphanapteryx bonasia), is an extinct, flightless rail. It was endemic to the Mascarene island of Mauritius, east of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. It had a close relative on Rodrigues island, the likewise extinct Rodrigues Rail, with which it is sometimes considered co-generic. Its relationship with other rails is unclear.

It was a little larger than a chicken and had reddish plumage with dark legs and a long, curved beak. The wings were small, and its legs were slender for a bird of its size. It is believed to have fed on invertebrates, and snails have been found with damage matching an attack by its beak. It was described as being attracted to red objects, which was exploited by humans during hunting.

The Red Rail was only known from 17th century descriptions and illustrations until subfossil remains were described in 1869. The last mention of the bird is from 1693, and it is thought to have gone extinct around 1700, due to predation by humans and invasive species brought by them. It has been suggested that late 17th century accounts of the extinct Dodo actually referred to the Red Rail.

Taxonomy

By the 19th century, the Red Rail was only known from a few contemporary descriptions and the sketches of Pieter van den Broecke and Sir Thomas Herbert, which were identified as either Apterornis bonasia or different Dodo species, Didus broecki and Didus herberti respectively, until united by Hugh Edwin Strickland in 1848.[2] Jacob Hoefnagel's painting, the Gelderland sketch, and Peter Mundy's description and sketch later surfaced, but there was still uncertainty about the identity of the bird.[3] In the 1860s, sub fossil foot bones and a lower jaw of the bird were found along with remains of other Mauritian animals in the Mare aux Songes swamp, and were described by Alphonse Milne-Edwards in 1869, who identified them as belonging to a rail. He combined the current genus name Aphanapteryx, which had been coined by Georg Ritter von Frauenfeld for the Hoefnagel painting, with the existing specific name broecki.[4] Due to nomenclatural priority, the genus name was later combined with the species name bonasia, which was coined by Edmond de Sélys Longchamps in 1848.[5] Longchamps had originally named the genus Apterornis, a name preocuppied by Aptornis, which had been named by Richard Owen in 1848.[6] Aphanapteryx means "invisible-wing", but the etymology of bonasia is unclear. Early accounts refer to Red Rails by the vernacular names for the Hazel Grouse, Tetrastes bonasia, so the name evidently originates there. The name itself perhaps refers to "bonasus", meaning bull in Latin, or "bonum" and "assum", meaning "good roast". It has also been suggested to be a Latin form of the French word "bonasse", meaning simple-minded or good-natured.[6]

More fossils were later found by Theodore Sauzier, who had been commissioned to explore the "historical souvenirs" of Mauritius in 1889.[7] A complete specimen was found by the barber Louis Etienne Thirioux who also found important Dodo remains.[8]

Apart from being a close relative of the Rodrigues Rail, the relationships of the Red Rail are uncertain. The two are commonly kept as separate genera, Aphanapteryx and Erythromachus, but have also been united as species of Aphanapteryx at times.[3] They were first generically synonymised by Edward Norton and Albert Günther in 1879, due to skeletal similarities.[9] Based on geographic location and the morphology of the nasal bones, it has been suggested that they may have been related to the genera Gallirallus, Dryolimnas, Atlantisia, and Rallus.[6] Rails have reached many oceanic archipelagos, which often leads to speciation and evolution of flightnessness.[3]

Description

From the subfossil bones, illustrations and descriptions, it is known that the Red Rail was a flightless bird, somewhat larger than a chicken. Subfossil specimens range in size, which may indicate sexual dimorphism, as is common among rails.[6] Its exact length is unknown, but it was about the size of a chicken. Its plumage was reddish brown all over, and the feathers were fluffy and hairlike; the tail was not visible in the living bird and the short wings likewise also nearly disappeared in the plumage.[10] It had a long, slightly curved, brown bill, and some illustrations suggest it had a nape crest.[8] It perhaps resembled a lightly built Kiwi, and it has also been likened to a Limpkin, both in appearance and behaviour.[3][10] The sternum and humerus were small, indicating that it had lost the power of flight. Its legs were long and slender for such a large bird, but the pelvis was compact and stout.[7] It differed from the Rodrigues Rail, its closest relative, in having a proportionately shorter humerus, a narrower and longer skull, and having shorter and higher nostrils. They differed considerably in plumage, based on early descriptions.[6] The Red Rail was also larger, with somewhat smaller wings, but their leg proportions were similar.[9] The pelvis and sacrum was also similar.[7]

Contemporary descriptions

The English traveller Peter Mundy visited Mauritius in 1638 and described the Rail as follows:

A Mauritius henne, a Fowle as bigge as our English hennes, of a yellowish Wheaten Colour, of which we only got one. It hath a long, Crooked sharpe pointed bill. Feathered all over, butte on their wings they are soe Few and smalle that they cannot with them raise themselves From the ground. There is a pretty way of taking them with a red cap, but this of ours was taken with a stick. They bee very good Meat, and are also Cloven footed, soe that they can Neyther Fly nor Swymme.[11]

The yellowish colouration instead of reddish has been used as argument for this referring to a distinct species, but it has been suggested it was due to it being a juvenile.[6]

Another English traveller, John Marshall, described them as follows in 1668:

Here are also great plenty of Dodos or red hens which are larger a little than our English henns, have long beakes and no, or very little Tayles. Their fethers are like down, and their wings so little that it is not able to support their bodies; but they have long leggs and will runn very fast, and that a man shall not catch them, they will turn so about in the trees. They are good meate when roasted, tasting something like a pig, and their skin like pig skin when roosted, being hard.[3]

Contemporary depictions

Much information about the external appearance of the bird comes from a painting attributed to Jacob Hoefnagel, thought to be based on a bird in the menagerie of Emperor Rudolph II in the early 1600s.[12] It is the only coloured depiction, showing the plumage as reddish brown, but it is unknown whether it was based on a stuffed or living bird.[8] The bird had most likely been brought alive to Europe, as it is unlikely that taxidermists were on board the visiting ships, and spirits were not yet used to preserve biological specimens. Most tropical specimens were preserved as dried heads and feet.[3] It was discovered in the Emperor's collection and published in 1868 by Georg von Frauenfeld, along with a painting of a Dodo from the same collection and artist.[4]

The travel journal of the Dutch East India Company ship Gelderland (1601–1603), rediscovered in the 1860s, contains good sketches of several now-extinct Mauritian birds attributed to the artist Joris Laerle, including a Red Rail. The bird appears to have been stunned or killed.[13] In addition, there are three other sketches drawn on Mauritius, they are rather crude, but differences in them were enough for several authors to suggest that each image depicted a distinct species, leading to the creation of several scientific names which are now synonymous with Aphanapteryx bonasia.[10]

There are also some depictions of what appear to be Red Rails in some of the 1620s Dodo paintings by Roelant Savery, including the famous "Edwards' Dodo", where a rail-like bird is seen swallowing a frog behind the Dodo, but this identification has been doubted.[8] A bird resembling a Red Rail is also figured in Francesco Bassano the Younger's painting Arca di Noè ("Noah's Ark").[10]

Behaviour and ecology

The Red Rail is discussed in almost every report about Mauritius from 1602 on; however, the details provided are repetitive and do not shed much light on the bird's life history. Its diet was never reported, but the shape of the beak indicates it could have captured reptiles and invertebrates.[3] There were many endemic land snails on Mauritius, including the extinct Tropidophora carinata, and subfossil shells have been found with damage matching attacks from the beak of the Red Rail.[14]

An anonymous Dutchman gave some description of behavioural traits in 1631:

The soldiers [Red Rails] were very small in stature and slow of foot, so they could be caught easily by hand, their armour or gun was their mouth, which was sharp and pointed, and which they used instead of a dagger, were very naked and [unrecognisable word], not hewing about like soldiers, run about in great disorder, now here, now there, not being true to each other at all.[3]

While it was swift and could escape when chased, it was easily lured by showing the birds a red cloth, which they approached to attack; a similar behaviour was noted in its relative, the Rodrigues Rail. The birds could then be picked up, and their cries when held would draw more individuals to the scene, as the birds, which had evolved in the absence of predators, were curious and not afraid of humans.[10] Sir Thomas Herbert described this behaviour towards red cloth in 1634:

The hens in eating taste like parched pigs, if you see a flocke of twelve or twenties, shew them a red cloth, and with their utmost silly fury they will altogether flie upon it, and if you strike downe one, the rest are as good as caught, not budging an iot till they be all destroyed.[3]

Many other of the endemic species of Mauritius went extinct after the arrival of man, so the ecosystem of the island is heavily damaged, and hard to reconstruct. Before humans arrived, Mauritius was entirely covered in forests, but very little remains today due to deforestation.[15] The surviving endemic fauna is still seriously threatened.[16] The Red Rail lived alongside other recently extinct Mauritian birds such as the Dodo, the Broad-billed Parrot, Thirioux's Grey Parrot, the Mauritius Blue Pigeon, the Mauritius Owl, the Mascarene Coot, the Mauritian Shelduck, the Mauritian Duck, and the Mauritius Night Heron. Extinct Mauritian reptiles include the Saddle-backed Mauritius giant tortoise, the Domed Mauritius giant tortoise, the Mauritian Giant Skink, and the Round Island Burrowing Boa. The Small Mauritian Flying Fox and the snail Tropidophora carinata lived on Mauritius and Réunion, but went extinct in both islands. Some plants, such as Casearia tinifolia and the Palm Orchid, have also become extinct.[3]

Extinction

To the Dutch sailors who visited Mauritius from 1598 and onwards, the fauna was mainly interesting from a culinary standpoint. The Dodo was sometimes considered rather unpalatable, but the Red Rail was a very popular gamebird for the Dutch and French settlers. The reports dwell upon the varying ease with which the bird could be caught according to the hunting method and the fact that when roasted it was considered a good substitute for pork.[10]

Johann Christian Hoffmann, who was on Mauritius in the early 1670s, described a Red Rail hunt as follows:

... [there is also] a particular sort of bird known as toddaerschen which is the size of an ordinary hen. [To catch them] you take a small stick in the right hand and wrap the left hand in a red rag, showing this to the birds, which are generally in big flocks; these stupid animals precipitate themselves almost without hesitation on the rag. I cannot truly say whether it is through hate or love of this colour. Once they are close enough, you can hit them with the stick, and then have only to pick them up. Once you have taken one and are holding it in your hand, all the others come running up as it to its aid and can be offered the same fate.[3]

Hoffman's account refers to the Red Rail by the German version of the Dutch name originally applied to the Dodo, "Dod-aers", and John Marshall used "Red Hen" interchangeably with "Dodo" in 1668. Mascarene expert Anthony Cheke has suggested that by the late 17th century, the name was transferred to the Red Rail, so that all post 1662 references to the Dodo are dubious.[17] A 1681 account of a "Dodo", previously thought to have been the last, mentioned that the meat was "hard", similar to the description of Red Hen meat.[3] Errol Fuller has also cast the 1662 "Dodo" sighting in doubt, as the reaction to distress cries of the birds mentioned matches what was described for the Red Rail.[10]

As it nested on the ground, pigs which ate their eggs and young probably contributed to its extinction. When François Leguat, who had become intimately familiar with the Rodrigues Rail in the preceding years, arrived on Mauritius in 1693, he remarked that the Red Rail had already become rare.[18] He was the last source to mention the bird, so it is assumed that it became extinct around 1700.[10]

230 years before Charles Darwin's theory of evolution, the appearance of the Red Rail and the Dodo led Peter Mundy to speculate:

Of these 2 sorts off fowl afforementionede, For oughtt wee yett know, Not any to bee Found out of this Iland, which lyeth aboutt 100 leagues From St. Lawrence. A question may bee demaunded how they should bee here and Not elcewhere, beeing soe Farer From other land and can Neither fly or swymme; whither by Mixture off kindes producing straunge and Monstrous formes, or the Nature of the Climate, ayer and earth in alltring the First shapes in long tyme, or how.[19]

See also

References

- ^ Template:IUCN

- ^ Strickland, H.E.; Melville, A. G. (1848). The Dodo and Its Kindred; or the History, Affinities, and Osteology of the Dodo, Solitaire, and Other Extinct Birds of the Islands Mauritius, Rodriguez, and Bourbon. London: Reeve, Benham and Reeve.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Cheke, A. S.; Hume, J. P. (2008). Lost Land of the Dodo: an Ecological History of Mauritius, Réunion & Rodrigues. T. & A. D. Poyser. ISBN 978-0-7136-6544-4.

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1869.tb06880.x, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1111/j.1474-919X.1869.tb06880.xinstead. - ^ de Sélys Longchamps, E. (1848): Résumé concernant les oiseaux brévipennes mentionnés dans l'ouvrage de M. Strickland sur le Dodo. Rev. Zool. 1848: 292–295.

- ^ a b c d e f Olson, S.: A synopsis on the fossil Rallidae In: Sidney Dillon Ripley: Rails of the World – A Monograph of the Family Rallidae. Codline. Boston, 1977. ISBN 0-87474-804-6

- ^ a b c Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1893.tb00001.x, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1111/j.1469-7998.1893.tb00001.xinstead. - ^ a b c d Hume, J. P.; Walters, M. (2012). Extinct Birds. London: A & C Black. pp. 134–136. ISBN 1-4081-5725-X.

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1098/rstl.1879.0043, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1098/rstl.1879.0043instead. - ^ a b c d e f g h Fuller, Errol (2001). Extinct Birds (revised ed.). New York: Comstock. pp. 96–97. ISBN 0-8014-3954-X.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1915.tb08192.x, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1111/j.1474-919X.1915.tb08192.xinstead. - ^ Rothschild, W. (1907). Extinct Birds (PDF). London: Hutchinson & Co.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.3366/anh.2003.30.1.13, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.3366/anh.2003.30.1.13instead. - ^ Griffiths Owen.L. & Florens Vincent F.B., Non-Marine Molluscs of the Mascarene Islands, Bioculture Press, Mauritius 2006, ISBN 99949-22-05-X

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1017/S0030605300020457, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1017/S0030605300020457instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1017/S0030605300012643, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1017/S0030605300012643instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.2006.00478.x, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1111/j.1474-919X.2006.00478.xinstead. - ^ Leguat, F. (1708). Voyages et Avantures de François Leguat & de ses Compagnons, en Deux Isles Desertes des Indes Orientales, etc (2 ed.). Amsterdam: Jean Louis de Lorme. p. 71.

- ^ Fuller, E. (2002). Dodo – From Extinction To Icon. London: HarperCollins.