Born to Run

| Born to Run | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | August 25, 1975[a] | |||

| Recorded | January 1974 – July 1975 | |||

| Studio | ||||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 39:23 | |||

| Label | Columbia | |||

| Producer |

| |||

| Bruce Springsteen chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Born to Run | ||||

| ||||

Born to Run is the third studio album by the American singer-songwriter Bruce Springsteen, released on August 25, 1975, by Columbia Records. Co-produced by Springsteen with his manager Mike Appel and the producer Jon Landau, its recording took place in New York. The album marked Springsteen's effort to break into the mainstream following the commercial failures of his first two albums. Springsteen sought to emulate Phil Spector's Wall of Sound production, leading to prolonged sessions with the E Street Band lasting from January 1974 to July 1975; six months alone were spent working on the title track.

The album incorporates musical styles including rock and roll, pop rock, R&B, and folk rock. Its character-driven lyrics describe individuals who feel trapped and fantasize about escaping to a better life, conjured via romantic lyrical imagery of highways and travel. Springsteen envisioned the songs taking place over one long summer day and night. They are also less tied to the New Jersey area than his previous work. The album cover, featuring Springsteen leaning on E Street Band saxophonist Clarence Clemons's shoulder, is considered iconic and has been imitated by various musicians and in other media.

Supported by an expensive promotional campaign, Born to Run became a commercial success, reaching number three on the U.S. Billboard Top LPs & Tape chart and the top ten in three others. Two singles were released, "Born to Run" and "Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out", the first of which became a radio and live favorite. The album's release generated extensive publicity, leading to backlash from critics who expressed skepticism over whether Springsteen's newfound attention was warranted. Following its release, Springsteen became embroiled in legal issues with Appel, leading him to tour the United States and Europe for almost two years. Upon release, Born to Run received highly positive reviews. Critics praised the storytelling and music, although some viewed its production as excessive and heavy-handed.

Born to Run was Springsteen's breakthrough album. Its success has been attributed to capturing the ideals of a generation of American youths during a decade of political turmoil, war, and issues for the working class. Over the following decades, the album has become widely regarded as a masterpiece and one of Springsteen's best records. It has appeared on various lists of the greatest albums of all time and was inducted into the National Recording Registry by the Library of Congress for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" in 2003. Born to Run received an expanded reissue in 2005 to celebrate its 30th anniversary, featuring a concert film and a documentary detailing the album's making.

Development

[edit]Bruce Springsteen's first two albums, Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. and The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle, were released in 1973 through Columbia Records. While the albums were critically acclaimed, both sold poorly.[1] By 1974 his popularity was limited to the East Coast of the United States,[2] and the label's confidence in him began to wane.[3][4] Management at Columbia had changed and they began to favor the then-upcoming artist Billy Joel.[5][6] Low morale plagued Springsteen's team, including both his manager, Mike Appel, and his backing group the E Street Band.[1] After Springsteen rejected CBS Records' suggestion to record in Nashville, Tennessee with session musicians and a brought-in producer,[b][5][8][9] the label agreed to finance one more album on the agreement that if it failed, they would drop him.[3][4][10] Appel successfully negotiated a slightly larger budget for the album but limited recording to 914 Sound Studios in Blauvelt, New York,[3] the studio Springsteen used for the recordings of his first two albums.[11]

I had these enormous ambitions for [the album]. ... I wanted to make the greatest rock record that I'd ever heard. I wanted it to sound enormous, to grab you by your throat and insist that you take that ride, insist that you pay attention—not just to the music, but to life, to being alive.[12]

—Bruce Springsteen, 2005

The phrase "born to run" came to Springsteen while lying in bed one night at his home in West Long Branch, New Jersey. He said the title "suggested a cinematic drama I thought would work with the music I was hearing in my head".[5][13] Inspired by the musical sounds and lyrical themes of 1950s and 1960s rock and roll artists such as Duane Eddy, Roy Orbison, Elvis Presley, Phil Spector, the Beach Boys, and Bob Dylan, Springsteen began composing what became "Born to Run".[14] He later wrote: "This was the turning point. It proved to be the key to my songwriting for the rest of the record."[15] He anticipated that sound he was seeking would be a "studio production".[16] The album became the first time Springsteen used the studio as an instrument rather than simply replicating the sound of live performances.[17]

Production history

[edit]914 Sound Studios

[edit]The recording sessions for the album began at 914 Sound Studios in January 1974.[15][18][19] Springsteen and Appel acted as co-producers; Greetings and Wild producer Jimmy Cretecos had departed Springsteen's company in early 1974, citing low profits.[1] Louis Lahav, the engineer from both albums, returned for these sessions. The members of the E Street Band were Clarence Clemons (saxophone), Danny Federici (organ), David Sancious (piano), Garry Tallent (bass), and Ernest Carter (drums);[20] Carter had replaced Vini "Mad Dog" Lopez, whom Springsteen fired in February over poor personal behavior.[1][21][22] The band went back and forth between studio recording and live concert performances.[23] Springsteen used the latter to develop new material,[15] and he spent more time in the studio refining songs than he had on the previous two albums.[24] The album's working titles included From the Churches to the Jails, The Hungry and the Hunted, War and Roses, and American Summer.[23]

Recording for "Born to Run" lasted six months.[18][25] Springsteen's perfectionism led to grueling sessions:[26] he obsessed over every syllable, note, and tone of every texture, and he struggled to capture the sounds he heard in his head on tape.[11][27][28] His aim for a Phil Spector-type Wall of Sound production meant multiple instruments were assigned to each track on the studio's 16-track mixing desk; each new overdub made the recording and mixing more difficult.[18][26] As he kept rewriting the lyrics,[29] Springsteen and Appel created several mixes containing electric and acoustic guitars, piano, organ, horns, synthesizers, and a glockenspiel, as well as strings and female backing vocalists.[30] "Born to Run" reportedly had up to five different versions.[25][31] According to Springsteen, the final song had 72 different tracks squeezed onto the 16 tracks of the mixing console.[29] Springsteen was pleased with the final mix,[26] completed in August 1974.[3] CBS/Columbia refused to release "Born to Run" as an early single, wanting an album to promote it.[4][32]

The same month "Born to Run" was completed, Sancious and Carter departed the E Street Band to form their own jazz-fusion band, Tone. They were replaced by Roy Bittan on piano and Max Weinberg on drums.[11][33][34] Bittan had a background in symphony orchestras while Weinberg had experience with various rock bands and Broadway productions. Bittan had previously known of Springsteen's music but Weinberg had not.[23][35] The two meshed well with the rest of the band, offering new musical insights and relaxed personalities that eased tensions that had built up over years of recording and performing.[34] On the album Bittan mostly replaced Federici, whose sole contribution was the organ part on "Born to Run".[26] Bittan later said he believed this was due to both men's different performing styles and Bittan wanting to "prove himself" as a new member of the group.[36]

Recording at 914 continued into late October 1974.[37] The band made attempts at "Jungleland", "She's the One", "Lovers in the Cold", "Backstreets", and "So Young and in Love", but faulty equipment and Springsteen's lack of direction halted progress.[38][37] The music critic Dave Marsh suggested that Springsteen remained at the subpar 914 Studios because studio costs built up, even though superior ones were available.[39] In November,[40] Appel sent "Born to Run" to various radio stations around the United States, which CBS executives viewed as professional misconduct.[3] The stunt generated interest in the track and anticipation built toward the album's release,[32][41] prompting Columbia to fund further sessions.[4][42] "Born to Run" became frequently requested on radio and at shows.[42]

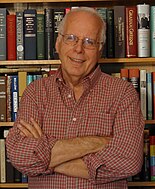

By January 1975, the band had been working for over a year with one finished track. Production continued to be plagued by faulty equipment, false starts, and Springsteen's desire for more takes.[43] A new track, "Wings for Wheels", debuted live in February.[44][45] Springsteen felt he lacked direction,[46] and he requested production advice from the writer and producer Jon Landau, who had criticized the production on Wild in an article for The Real Paper.[47][28] The two met in Boston in April 1974 and developed a close friendship after.[32][48][49] In February 1975, Landau was invited to a session, where he suggested moving the saxophone solo on "Wings for Wheels" to the end rather than in the middle.[47][50] Springsteen liked the change and hired Landau as co-producer of the album.[50][51]

Record Plant

[edit]In March 1975,[c] Landau moved the recording sessions from 914 to the superior Record Plant in Manhattan.[50][51] Landau helped Springsteen regain focus and direction with a fresh perspective.[46][47][54] Springsteen told Rolling Stone in 1975: "[Landau] came up with the idea, 'Let's make a rock and roll record.' Things had fallen down internally. He got things on their feet again."[55] Appel and Landau had disagreements on production choices, which Springsteen had to resolve.[46][56] Like the band, the two helped Springsteen complete already devised ideas, not think of new ones.[57] Louis Lahav was unavailable due to family commitments so these sessions were engineered by Jimmy Iovine.[47][58]

Sessions at the Record Plant lasted from March to July 1975.[52][58] Apart from a few live performances, Springsteen spent most of these months working on the album.[59] The sessions were grueling,[58] dragging on despite increased professionalism brought by Landau and Iovine.[60] While the backing tracks and vocals were recorded with little difficulty, Springsteen struggled with his overdubs and completing the writing of the lyrics and arrangements.[61] Springsteen obsessively labored over[58] and sometimes spent hours revising single lines[62] or taking days to figure out the song arrangements.[61] Springsteen later said: "[The sessions] turned into something that was wrecking me, just pounding me into the ground."[63] Weinberg called it the hardest project of his career, and Federici said "[we] ate, drank, and slept [that album]".[58] Work was mostly done between 3 p.m. and 6 a.m. the following morning.[61]

"Wings for Wheels", now called "Thunder Road", was finished in April. Springsteen reportedly took 13 hours to complete his guitar parts.[64] "Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out" and "Night" followed in May.[65][66] For "Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out", Springsteen hired the Brecker Brothers (Randy and Michael), David Sanborn, and Wayne Andre to play horn parts.[d][67] Springsteen and Bittan failed to write proper horn parts by the time the players arrived to record,[67] so Springsteen's friend and former Steel Mill bandmate Steven Van Zandt conceived them on the spot in the studio. Van Zandt joined the E Street Band shortly after.[68][69] Springsteen used lyrical ideas from "She's the One" to complete "Backstreets", originally "Hidin' on the River".[11] "Meeting Across the River", originally "The Heist", featured Richard Davis on double bass. Davis had previously contributed to "The Angel" on Greetings.[65] "Jungleland" featured violin from Suki Lahav, wife of Louis Lahav,[23][70] and a long saxophone solo from Clemons, which he spent 16 hours replaying to Springsteen's satisfaction;[71] the latter dictated almost every note played.[72] Clemons played several different solos, bits of which were then edited together into one piece; he then reproduced the final result.[38]

Mixing

[edit]According to Iovine, the album was mixed in "nine days straight".[73] The final days were hectic; the band worked vigorously between recording for the album and rehearsing for an upcoming tour scheduled to start on July 20.[73][74] Springsteen wrote in his 2016 autobiography Born to Run: "In a three-day, 72-hour sprint, working in three studios simultaneously, Clarence and I finishing the 'Jungleland' sax solo, phrase by phrase, in one, while we mixed 'Thunder Road' in another, singing 'Backstreets' in a third."[75] Springsteen was demanding and refused to compromise,[76] saying at the time that he could "only hear the things that were wrong with it".[77] Appel and Landau fought to keep certain tracks on the finished album. Appel succeeded in leaving "Linda Let Me Be the One" and "Lonely Night in the Park" off and keeping "Meeting Across the River" on.[78] Mixing lasted until the morning of July 20, just before the tour began.[79][80]

Born to Run was mastered by the engineer Greg Calbi[81] while the band were on the road.[82] Springsteen was furious about the initial acetate, throwing it into the swimming pool of the hotel he was staying at.[28][76] He contemplated scrapping the entire project and re-recording it live before he was stopped by Landau.[76][79] Springsteen was sent multiple mixes as he was on the road and rejected all but one, which he approved in early August.[82][83]

Outtakes

[edit]The seven known outtakes from the album are "Linda Let Me Be the One", "Lonely Night in the Park", "A Love So Fine", "A Night Like This", "Janey Needs a Shooter", "Lovers in the Cold", and "So Young and in Love".[84] "Linda Let Me Be the One" and "So Young and in Love" were released on the Tracks box set in 1998.[85] Rough mixes of the unreleased songs "Lovers in the Cold" ("Walking in the Street") and "Lonely Night in the Park" surfaced in 2005, when they made their debut on E Street Radio.[85] "Janey Needs a Shooter" was later re-worked by Springsteen and Warren Zevon into the track "Jeannie Needs a Shooter" for Zevon's 1980 album Bad Luck Streak in Dancing School.[85] A 2019 recording of the original "Janey Needs a Shooter" was released on Springsteen's 2020 album Letter to You.[86]

Music and lyrics

[edit]The music on Born to Run includes styles such as rock and roll, pop rock, R&B, and folk rock.[87][88] The author Peter Ames Carlin states that the album captures "the essence of fifties rock 'n' roll and the beatnik poetry of sixties folk-rock, projected onto the battered spirit of mid-seventies America".[89] Springsteen wrote most of the songs on piano,[90][91] which Kirkpatrick felt gave them "a particular melodic feel".[92] Springsteen later said Bittan's piano "really defined the sound" of the album.[93] The record's production is similar to Phil Spector's Wall of Sound,[90][94] in which layers of instruments and complex arrangements are combined to make each song resemble a symphony.[95] Springsteen said that he wanted Born to Run to sound like "Roy Orbison singing Bob Dylan, produced by Spector".[96] He used Orbison's style for his vocal delivery and Duane Eddy as inspiration for his guitar parts.[95][97] The writer Frank Rose emphasized Springsteen's homage to girl groups from the 1960s, such as the Shirelles, the Ronettes, and the Shangri-Las, ones who embellished themes of heartbreak and doo-wop sounds produced by Spector.[98] The songs feature musical introductions that set the tone and scene for each.[93][96]

Lyrically, I was entrenched in classic rock and roll images, and I wanted to find a way to use those images without their feeling anachronistic. ... [Born to Run] was the album where I left behind my adolescent definitions of love and freedom ... [it] was the dividing line.[99]

—Bruce Springsteen, Songs, 2003

Springsteen envisioned the album's songs as taking place during one summer day and night.[91][100][101] According to the writer Louis Masur, the album is centrally driven by "loneliness and the search for companionship".[102] The characters are regular people[103] who are lost[104] and feel trapped in their lives; different places, such as streets and roads, offer a way out but are not ideal places.[105] Described by Treble's Hubert Vigilla as a "four corners approach" to album sequencing,[106] both sides of the original LP began with songs that were optimistic and promised hope and ended with songs of betrayal and pessimism.[57][101] Across the album's eight songs,[107] Springsteen writes about the night and the city ("Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out", "Backstreets", and "Meeting Across the River"); an irresistible real or imaginary woman ("She's the One"); the enslavement of the working class ("Night"); and the highway as a means of escape and coming-of-age journey ("Thunder Road", "Born to Run", and "Jungleland").[108] The journalist Veronika Hermann noted the album is mostly driven by actions such as running, meeting, hiding, and driving.[109]

Born to Run was written during a time when the idea of the American Dream was unobtainable to many Americans in the aftermath of the Vietnam War, Watergate scandal, and the 1973 oil crisis.[108] Carlin writes that Springsteen's hopeful songs, containing ideals such as that a road can take you anywhere, were "stunning" during a period marked by assassinations, war, political corruption, and collapse of the hippie subculture.[89] Hermann analyzed the lyrics as experiments in nostalgia, arguing that the "heroes and heroines of Born to Run are facing the loss of security and stability, [and] facing the consequences of a lost war," leading to the choice to run away from the "American dream".[109] Springsteen worked a "very, very long" time writing the lyrics because he wanted to avoid tropes of "classic rock 'n' roll clichés", turning them instead into fully developed and emotional characters: "It was the beginning of the creation of a certain world that all my others would refer back to, resonate off of, for the next 20 or 30 years."[93]

The songs are largely autobiographical, inspired by the noir-like B movies Springsteen enjoyed at the time;[92] he wanted to experience and capture new ideals based on his life experiences at the time.[93][108] Like his first two albums, Born to Run includes religious imagery, specifically the idea of "searching",[110] although it is undercut by a darker, apocalyptic landscape.[104] Unlike Greetings and Wild, however, most of the songs on Born to Run are not specifically tied to New Jersey and New York, instead shifting to all of the United States in an attempt to be more accessible to a wider audience.[91][108][111][112] Springsteen has said that "most of the songs are about being nowhere".[113]

Side one

[edit]"Thunder Road" is an invitation to travel on a long journey,[64] taking inspiration from the 1958 film of the same name.[11] The song's narrator pleads with a romantic partner to join him in leaving their life behind to start anew,[114] believing there is no time to wait and they must act now.[115] Masur argues the song "lays out hopes and dreams, and the remainder of the album is an investigation into whether, and in what ways, they can be realized".[116] Kirkpatrick believes the track to be a rewritten version of Wild's "Rosalita (Come Out Tonight)" with a "less innocent, more realistic perspective".[117] Described by Billboard's Kenneth Partridge as a "five-minute pop opera",[118] the music builds throughout the runtime;[119] the instruments join in as the narrator's vision solidifies.[120] AllMusic's James Gerard characterizes the tone as more melancholic than uplifting.[119]

"Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out" follows a character named Bad Scooter who is "searching for his groove" and "a place to fit in".[121] Part autobiographical and part mythological,[118] the song tells Springsteen and the E Street Band's story as they struggle to find commercial success up to that point; they find success after the "Big Man" (Clemons on saxophone) joins the band in the third verse.[11][67][114][122] Musically, it is a funky R&B song led by brass horns;[67][122][123] the authors Philippe Margotin and Jean-Michel Guesdon compared it to the sound of a Stax record.[67] In his 2003 book Songs, Springsteen described "Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out" as a "band bio and block party".[99]

"Night", the shortest song on the album,[11][118] follows a man who is a slave to the working life. He dreads working his nine-to-five job, but his love for drag racing motivates him to work so he can live for the night.[123][124] Similar to other album tracks, it uses the highway as a means for escape.[e][66] Musically, the song contains various minor and major key shifts in the music; Masur argues the minor key "condemns the monotonous world of daytime work" and the major key "offers the possibilities of screeching off into the night".[125] Margotin and Guesdon highlight the wall of sound production and compare its rock-and-roll sound to Chuck Berry.[66]

"Backstreets" features a long piano-led intro.[126] Described by Masur as "operatic and theatrical",[127] the band took inspiration from various Dylan and Orbison songs for the instrumental parts.[126] The song tells the story of the narrator's friendship with an individual named Terry, using both realistic and poetic imagery. The two become close until their relationship is broken after Terry leaves the narrator for someone else, after which the narrator "reflects that he and Terry did not turn out to be the heroes 'we thought we had to be'". Terry's gender is unclear, leading some reviewers to interpret the relationship as homosexual.[f][g][114][118][106] The song contains autobiographical elements related to Springsteen's youth, with cinematic references.[126]

Side two

[edit]"Born to Run" uses the automobile as a means to escape from a depressing life.[32] The characters, described as "tramps",[129] include the narrator and a girl named Wendy. The former works a dreary job, "sweating out" the "runaway American dream", and joins a car community at night.[123] He tells Wendy the town they live in is a "death trap" and they need to leave "while [they're] young" because "tramps like us ... were born to run".[26] Reviewers have analyzed the song's anthemic message as containing both an "underlying sadness"[32] and "a feeling of desperation",[123] as the narrator promises Wendy they will one day reach the promised land, but he does not know when. He simply wants to run away with her to "help him discover if his youthful notions of love are real", and "pledges his desire to die with her in the street" and love her "with all the madness in [his] soul".[123] The song's music combines rock and roll and hard rock with rockabilly, jazz, and Tin Pan Alley,[30] complete with a Wall of Sound production.[26] AllMusic's Jason Ankeny described the song as "a celebration of the rock & roll spirit, capturing the music's youthful abandon, delirious passion, and extraordinary promise with cinematic exhilaration".[130]

"She's the One" is about the narrator's complete obsession for a girl.[131][132] The girl, however, is a liar and bad for him, yet he keeps returning to her.[11][117] Springsteen never revealed the song's inspiration, although Margotin and Guesdon suggest it was Karen Darvin, Springsteen's girlfriend at the time.[36] The song musically incorporates a Bo Diddley beat.[36][118][131][132] The jazzy[11] "Meeting Across the River" musically and lyrically departs from the previous songs,[133] utilizing piano and trumpet to create what Margotin and Guesdon describe as a "film noir jazz ambience" that "clashes with the other tracks".[65] In it, the narrator and his partner Eddie are small-time gangsters who plan an illegal deal across the Hudson River, striving for a big score that will earn him a large amount of money to impress his girlfriend.[11][65][118][134] With themes of despair and hopelessness, the song ends before a narrative resolution, leaving whether or not the gangsters succeeded ambiguous.[133]

"Jungleland" takes place in the titular location, where a meeting between gang members at midnight is interrupted by the police.[38][135] With a dark atmosphere,[38] the track observes a New Jersey gang member known as the Magic Rat, who escapes law enforcement in Harlem with his unnamed partner referred to as the "barefoot girl". Towards the end, the Rat and the girl's relationship has broken apart; she leaves him, and he is killed in the streets.[136] The Rat is gunned down by his "own dream", symbolizing, in Masur's words, that "the runaway American dream will kill us in the end, and the dream of escape is just another version that entraps us".[135] Following his demise, destruction continues across the streets until they are left in complete devastation.[137] Over nine minutes in length,[138] the track is led by Springsteen's vocal, Bittan's piano, and Suki Lahav's violin,[38] and features an extended saxophone solo from Clemons that lasts for over two minutes.[135]

Artwork and packaging

[edit]

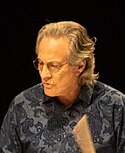

The cover art of Born to Run was taken by the photographer Eric Meola at his personal studio on June 20, 1975. Springsteen's busy recording schedule meant he kept missing shooting dates.[139][113] When he finally showed up, he brought Clemons,[20] whom he wanted on the cover.[139][140] Meola shot 900 frames in the three-hour session,[h][20] some of which showed Springsteen under a fire escape, tuning a radio, and with a guitar;[139] unused shots were used by Columbia for advertising.[i][140]

In the chosen black-and-white shot,[89][140] Springsteen is holding a guitar while leaning against Clemons.[20] Springsteen is wearing a black leather jacket, and Clemons is in a white shirt with a striped pattern and wearing a black hat.[89] Meola said the shot was a clear standout:[139] "I wanted something that was nearly impossible to print, but beautiful to look at if printed perfectly—somehow innocent yet street-smart."[140] An Elvis Presley pin appears on Springsteen's guitar strap, which he wore to display Presley's inspiration on him as a musician.[143] His guitar, a Fender Telecaster with an Esquire neck,[144] later appeared on the covers of Live 1975–85 (1986), Human Touch (1992), and Greatest Hits (1995).[20] The Born to Run cover was included in a Rolling Stone readers' poll of the best album covers of all time in 2011.[145] Masur called it "classic" and "one of the most iconic images in rock history".[113]

The image covers both sides of the LP sleeve; the inside features lyrics and a portrait of Springsteen.[20] Columbia's art director John Berg created the fold-over sleeve, and Andy Engel was responsible for the typography.[139] Berg stated that "it probably took a week of negotiating" with the label to create the fold-over cover because "it was breaking the code; we didn't do that unless we had two records".[139] Landau's name was misspelled as "John" instead of "Jon" on the initial pressings; Columbia printed stickers to cover up the error—reportedly up to 400,000.[1] A few original pressings have "Meeting Across the River" billed under its initial title "The Heist", and the original album cover has the title handwritten with a broad-nib pen. These copies, known as the "script cover", are very rare and among the most sought after of Springsteen memorabilia.[146]

Springsteen and Clemons occasionally remade the cover pose onstage during their concerts.[101] The pose has since been imitated by other singers and musicians, including Cheap Trick on the 1983 album Next Position Please, Mai Kuraki on the cover of her 2001 single "Stand Up", Tom and Ray Magliozzi on the cover of the 2003 Car Talk compilation Born Not to Run: More Disrespectful Car Songs, and Los Secretos for their 2015 album Algo prestado.[1][147] Outside of music, the webcomic strip Kevin and Kell imitated the pose on a Sunday strip entitled "Born to Migrate", featuring Kevin Dewclaw as Springsteen with a carrot and Kell Dewclaw as Clemons with a pile of bones, and the Sesame Street characters Bert and the Cookie Monster imitated the pose on the cover of the Sesame Street album Born to Add.[147][148]

Release and promotion

[edit]Springsteen and the E Street Band went on a tour of the U.S. East Coast on July 20, 1975, immediately after mixing on Born to Run was completed; Springsteen approved the final master recording while on the road.[149] The tour continued into August, including an all sold-out five-night, ten-show stint at the Bottom Line nightclub in Greenwich Village.[150] Columbia purchased one-fifth of the venue tickets for rock journalists and media for promotion.[151] Expectations were high. Clemons remembered: "We were right on the verge. If we had flopped at the Bottom Line, it would have been very detrimental to us emotionally."[152] The shows were a major success, receiving praise from both critics[153] and from Columbia's former president Clive Davis.[150] Kirkpatrick stated they "showed rock fans and media alike that Springsteen was no creation of industry hype; he was the real deal".[154] Rolling Stone later included the shows in a 1987 list chronicling 20 concerts that changed rock and roll.[152]

Born to Run was accompanied by a $250,000 promotional campaign by Columbia/CBS,[77][155] directed at both consumers and the music industry, led by the executive Glen Brunman.[150] In the buildup to the album's release, CBS spent $40,000 on advertisements that utilized Springsteen's first two albums and Landau's "I saw rock and roll future and its name is Bruce Springsteen" quote, which had been published in The Real Paper after Landau witnessed Springsteen perform "Born to Run" for the first time live in May 1975.[j][32] The ads increased sales of both albums significantly enough to chart on the Billboard Top LPs & Tape chart, barely above number 60, two years after their original releases.[80] Preorders for Born to Run were upwards of 350,000 units, more than twice the sales of Greetings and Wild combined.[157]

Released on August 25, 1975,[a][12][94][160] Born to Run peaked at number 3 on the Billboard Top LPs & Tape chart,[161] topped the Record World chart[155] and reached number 36 on the U.K. Albums Chart.[k][163] Elsewhere, Born to Run reached number 7 in Australia,[164] the Netherlands,[165] and Sweden,[166] 20 in Ireland,[167] 26 in Norway,[168] 28 in New Zealand,[169] and 31 in Canada.[170] By the end of 1975, it had sold 700,000 copies.[171] By 2022, Born to Run was certified seven times platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) in the US.[159] The album was supported by two singles. The first, "Born to Run" with "Meeting Across the River" as the B-side, was released on August 25, 1975,[26] reached number 23 on the Billboard Hot 100,[172] and proved popular with radio stations and live audiences.[171] The second, "Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out" backed by "She's the One",[67] appeared in January 1976[173] and reached number 83.[11]

Media hype and backlash

[edit]The album was highly anticipated and publicized. In October 1975,[174] Springsteen became the first artist to appear on the covers of the magazines Time and Newsweek simultaneously.[175] Time's Jay Cocks focused on him as an artist,[176] while Newsweek's Maureen Orth focused on Columbia's promotional campaign[172][175] and the hype surrounding Springsteen,[176] insisting that he was an industry-made pop star.[177]

The question of hype became a story in itself, as critics wondered if Springsteen was legitimate or the product of record company promotion.[178][179] The journalist John Sinclair of the Ann Arbor Sun claimed that Dave Marsh and Jon Landau were "co-conspirators on a massive Springsteen hype".[180] Examinations on the hype continued after the album's release with articles by BusinessWeek and England's Melody Maker, the latter arguing that Springsteen was "no hype" at all because he "is really good", and "'hype' only services artists who do not deserve the attention".[181] In retrospect, Masur stated: "Most of the backlash against Springsteen came in the form of disgust with the hype, not the music, even though writing about the hype only fed the publicity machine."[182]

Springsteen was hurt by the media backlash, particularly an article by Henry Edwards in The New York Times that slandered both himself and Born to Run.[178][181][183] He felt that the publicity got out of his control[184] and Columbia's campaign that labeled him the future of rock and roll was a mistake.[185][186] He also reportedly felt a loss of innocence after the album's release, claiming to have reached a low point in the immediate months.[185] When the backlash subsided, sales tapered off and Born to Run was off the chart after 29 weeks.[187] In his 1999 book Flowers in the Dustbin, former Rolling Stone and Newsweek writer James Miller wrote that the "mass-marketing" of Springsteen in the U.S. and David Bowie's Ziggy Stardust in the U.K. led to the notion that "the age of innocence in rock was well and truly over—probably forever".[188]

Critical reception

[edit]Born to Run received highly positive reviews from music critics,[189] particularly for its cinematic storytelling and Wall of Sound production.[11] Greil Marcus wrote in Rolling Stone that Springsteen enhances romanticized American themes with his majestic sound, ideal style of rock and roll, evocative lyrics, and an impassioned delivery that defines a "magnificent" album.[190] In The New York Times, John Rockwell described Born to Run as a masterpiece of "punk poetry" and "one of the great records of recent years".[179] In The Village Voice, Robert Christgau felt that Springsteen condenses a significant amount of American myth into songs, and often succeeds in spite of his tendency for histrionics and "pseudotragic beautiful loser fatalism".[191]

Several critics expected Born to Run to lead to Springsteen crossing over into mainstream success.[179][192][193] Reviewers praised the vocal performances,[194][195] music,[l] and production.[192] Compared to Springsteen's earlier albums, critics felt the lyrics were more accessible and possessed a "universal quality that transcends the sources and myths he drew upon".[179][200] Lester Bangs remarked in Creem that he is "no longer cramming as many syllables as possible into every line".[197] The performances of the E Street Band were also highlighted, particularly Clemons.[192][201]

Some critics, including Bangs and Cocks,[197][202] hailed Springsteen as a visionary destined to save the rock genre[203] from, in Stephen Holden's words, "its present state of enervation".[194] Bangs said Springsteen "reminds us what it's like to love rock 'n' roll like you just discovered it, and then seize it and make it your own with certainty and precision".[197] Robert Hilburn of the Los Angeles Times called Born to Run an "essential" album, stating: "It has been a long time since anyone in rock has put so much passion and ambition in an album."[204] In Circus Raves, Holden placed Born to Run amongst the decade's great albums with Layla (1970), Who's Next (1971), and Exile on Main St. (1972),[194] and David McGee placed Springsteen amongst rock greats such as Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and Bob Dylan.[196]

Born to Run received negative reviews from a few critics, who found the production excessive and "heavy-handed",[193][205] the songs "formulaic",[205] "an effusive jumble" and "undistinguished",[178] and felt Springsteen himself lacked a definitive vocal personality.[206] Langdon Winner argued in The Real Paper that, because Springsteen consciously adheres to traditions and standards extolled in rock criticism, Born to Run is "the complete monument to rock and roll orthodoxy".[207] Mike Jahn of High Fidelity complained about the songwriting, believing Springsteen was becoming typecast as a "character composer" after three albums.[208] Roy Carr of the NME unfavorably compared Springsteen to David Bowie, believing he lacked the latter's "breath of vision".[206] Carr also found the music uninspired and argued Springsteen himself "often tries too hard, going right over the top on many occasions as a result".[206] More moderately, Jerry Gilbert of Sounds believed Born to Run was not as "essential" as Greetings and Wild, but had enough "distinction" from the two albums to stand on its own: "I have grown to love it but newcomers to Bruce's music would be better advised to check out what the critics have been raving about in the past. Old fans will need to persevere."[201]

Born to Run was voted the third best album of 1975 in the Pazz & Jop, an annual critics poll run by The Village Voice, behind Bob Dylan and the Band's The Basement Tapes and Patti Smith's Horses.[209] Christgau, the poll's creator, ranked it 12th on his own year-end list.[210]

Tours and Appel lawsuit

[edit]

Springsteen and the E Street Band—Bittan, Clemons, Federici, Tallent, Weinberg, and Van Zandt—continued touring the U.S. throughout the remainder of 1975 to promote Born to Run, performing to larger audiences following the album's success.[211] In mid-November, the band traveled to Europe to perform their first shows outside North America.[212][213]

The first gigs were two performances at the Hammersmith Odeon in London.[212] Springsteen was displeased with the venue's advertisements, personally tearing down the lobby posters and ordered the buttons with Landau's "future of rock and roll" quote printed on them not be given out.[214][215] The first show drew mixed reviews from British reviewers. While his stage presence was positively received, others noted the difference in British and American cultures equated to poor audience responses.[216] Springsteen thought the show was a disaster.[m][213][215] Upon their return to the U.S., the band played five sold-out shows at the Tower Theater in Philadelphia at the end of December.[n][220]

By 1976, Springsteen had disagreements with Appel over the direction of his career; Appel wanted to capitalize on Born to Run's success with a live album, while Springsteen wanted to return to the studio with Landau.[221][222][223] Springsteen was also concerned with the lack of personal revenue given the album's success.[224] Realizing that the terms of his record contract were unfavorable, he sued Appel in July 1976 for ownership of his work. The resulting legal proceedings prevented him from recording in a studio for almost a year,[o] during which he continued touring with the E Street Band.[225][226] The second leg of the Born to Run Tour, nicknamed the Chicken Scratch tour, ran from March to May throughout the American South.[227][228]

Springsteen wrote new material on the road and at his farm home in Holmdel, New Jersey, reportedly amassing between 40 and 70 songs.[225][226] He continued performing for nine months between August 1976 and May 1977, dubbed the Lawsuit tour, debuting new songs such as "Something in the Night" and "The Promise" that became live favorites.[229][230] The lawsuit reached a settlement on May 28, 1977; Springsteen bought out his contract with Appel, who received a lump sum and a share of royalties from the first three albums.[p][222][225][231] Springsteen and the band immediately entered the studio to record the follow-up to Born to Run at the start of June, with Landau co-producing.[232] The recording sessions lasted nine months[233] as Springsteen demanded perfection from the musicians and moved between different studios.[225] The album, Darkness on the Edge of Town, was finally released in June 1978, three years after Born to Run.[234]

Legacy

[edit]The success of Born to Run saved Springsteen's career[235] and launched him to stardom.[24][236][237] The album established a solid national fan base for Springsteen, which he built on with each subsequent release.[238] According to Kirkpatrick, it "not only gave Springsteen his first hit record, it transformed seventies rock music while pushing the boundaries of what a singer-songwriter could achieve within the rock genre".[239] Hilburn and Carlin compare Born to Run to albums that "established a sound and identity powerful enough to permanently alter the perceptions of those who heard it", including Elvis Presley's first album (1956) and The Sun Sessions (1976), the Beatles' American debut Meet the Beatles! (1964), Bob Dylan's Highway 61 Revisited (1965) and Blonde on Blonde (1966), and Nirvana's Nevermind (1991).[240][241] Some critics argued Born to Run represented an amalgamation of the previous two decades of rock and roll that would push the next two decades of rock and beyond forward.[242][241] In a 2005 article in Treble, Hubert Vigilla referred to the album as "the Great American Rock and Roll Record".[106]

Springsteen and the E Street Band have performed Born to Run in its entirety on several occasions,[91] including at the Count Basie Theatre in Red Bank, New Jersey, on May 7, 2008,[243] at the United Center in Chicago, Illinois, on September 20, 2009,[244] and other shows on the fall 2009 leg of the Working on a Dream Tour.[245] It was also partly or entirely performed on certain shows of the 2013 Wrecking Ball World Tour.[246] The full album was again performed on June 20, 2013, at the Ricoh Arena in Coventry, England, and dedicated to the memory of the actor James Gandolfini, who had died of a heart attack the previous day.[q][247]

Analysis

[edit]The success of Born to Run was tied to the fears of growing old held by a generation of late teenagers. Having missed the 1950s beat era and 1960s civil rights and anti-war movements, teenagers in the mid-1970s felt disconnected in an era of political turmoil with the Vietnam War and the resignation of president Richard Nixon.[248] The decade was also plagued by stagflation that affected working class Americans, resulting in the loss of the American dream for many.[249] Commentators note that Born to Run collectively captured the ideals of an entire generation of American youths[28][250] and "spoke to the cultural shift" between the 1960s and 1970s.[248] Joshua Zeitz of The Atlantic summarized: "Springsteen embodied the lost '70s—the tense, political, working-class rejection of America's limitations."[249] Far Out's Tim Coffman argued that Springsteen effectively embodied what it meant to be "a down-and-out working-class kid in America, dreaming of a better life".[138] Springsteen himself stated in 2005:[251]

The thing people tend to forget about Born to Run is that it was post-Watergate, post-Vietnam. People just didn't feel that young anymore, and that is part of what made that record present because I was dealing with a lot of classic rock imagery and classic rock sounds but I was writing in a particular moment when people had sort of their legs cut out from underneath them.

Retrospective reviews

[edit]| Retrospective reviews | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Chicago Tribune | |

| Christgau's Record Guide | A[253] |

| The Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| MusicHound Rock | |

| New Musical Express | 9/10[256] |

| Q | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

| Sputnikmusic | 5/5[259] |

| Tom Hull – on the Web | B+[260] |

Retrospective reviewers consider Born to Run a masterpiece[r] and one of Springsteen's best works.[s] It has been described as a timeless record[267][101] that set the stage for a career marked by a signature, distinctive sound and lyrics detailing aspirations towards the American dream.[118][237] Further praise was given to the instrumentation between Springsteen and the E Street Band,[250] and for its improvements over its predecessor, Wild.[94][101] Lou Thomas of BBC Music described the album as "a classic, honest musical expression of hope, dreams and survival".[268] Another writer from The Guardian, Michael Hann, said Born to Run was "the album where Springsteen starts to make the transition from a musician to an idea, a representation of a set of personal and musical values".[264]

Despite its acclaim, Born to Run has attracted negative attention from writers who feel the production is "too overblown",[269] and presents Springsteen as "more of a synthesist than an innovator".[252] AllMusic's William Ruhlmann conversely argues that "to call [the album] overblown is to miss the point", as doing so was Springsteen's intention, concluding that "it declared its own greatness with songs and a sound that lived up to Springsteen's promise".[94] In a later piece for Blender magazine, Christgau wrote that the record's major flaw was its pompous declaration of greatness, typified by elements such as the "wall-of-sound, white-soul-at-the-opera-house" aesthetic and an "unresolved quest narrative". Nonetheless, he maintained Born to Run was important for how "its class-conscious songcraft provided a relief from the emptier pretensions of late-hippie arena-rock".[270] PopMatters writer Christopher John Stephens argued the album's strengths can be viewed as its weaknesses.[271]

Rankings

[edit]Born to Run has frequently appeared on lists of the greatest albums of the 1970s[237][250][272] and of all time.[273][235] NME's Matthew Taub argued that Born to Run is "probably the single best rock album of the 1970s, and easily one of the finest ever recorded".[262] American Songwriter included it in a 2023 list compiling 10 albums that shaped the 1970s music landscape.[272] In 1987, Rolling Stone ranked it number 8 in a list of the "100 Best Albums of the Last Twenty Years"[274] and in 2003, the magazine ranked it 18th on its list of the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time,[275] maintaining the rating in a 2012 revision and dropping a few slots to number 21 in the 2020 reboot of the list.[276] In 2000, NPR included Born to Run in a list compiling the 100 most important albums in the 20th century.[273] A year later, the TV network VH1 named it the 27th-greatest album of all time,[277] and in 2003, it was ranked as the most popular album of all time in the first Zagat Survey Music Guide.[278] The album was also voted number 20 in the third edition of Colin Larkin's All Time Top 1000 Albums (2000),[279] and was included in the book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die (2006).[280] In Apple Music's 2024 list of the 100 Best Albums, the album ranked number 22.[281]

In 2003, Born to Run was added to the National Recording Registry by the Library of Congress for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[282] In December 2005, U.S. New Jersey representative Frank Pallone and 21 co-sponsors sponsored H.Res. 628, a bill that would have celebrated the 30th anniversary of Born to Run and Springsteen's overall career. In general, resolutions honoring native sons are passed with a simple voice vote. The bill failed upon referral to the House Committee on Education and the Workforce.[283]

Reissues

[edit]| 30th Anniversary Edition | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Source | Rating |

| Blender | |

| Entertainment Weekly | A−[284] |

| The Guardian | |

| Pitchfork | 10/10[111] |

| Stylus Magazine | A[285] |

Born to Run was reissued in 1977, 1980, and 1993.[158] On November 15, 2005,[286] Columbia reissued the album as an expanded box set to mark the album's 30th anniversary. Titled the 30th Anniversary Edition, the package included a remastered CD version of the original album, and a DVD containing a documentary on the making of the album called Wings for Wheels, and a concert film of Springsteen and the E Street Band at the Hammersmith Odeon in London on November 18, 1975.[217] Wings for Wheels features interviews with Springsteen and the E Street Band members, with a bonus film of a 1973 performance in Los Angeles.[284] The 30th Anniversary Edition received critical acclaim, with several praising the remastered sound.[111][285][286] Wings for Wheels won the Grammy Award for Best Long Form Music Video at the 49th Annual Grammy Awards in 2007.[287]

In 2014, a new remaster by the engineer Bob Ludwig was included in The Album Collection Vol. 1 1973–1984, a boxed set composed of remastered editions of his first seven albums.[288] All seven albums were released separately as single discs for Record Store Day in 2015.[289][290]

Track listing

[edit]All tracks are written by Bruce Springsteen.[291]

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Thunder Road" | 4:49 |

| 2. | "Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out" | 3:11 |

| 3. | "Night" | 3:00 |

| 4. | "Backstreets" | 6:30 |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Born to Run" | 4:30 |

| 2. | "She's the One" | 4:30 |

| 3. | "Meeting Across the River" | 3:18 |

| 4. | "Jungleland" | 9:34 |

| Total length: | 39:23 | |

Personnel

[edit]Adapted from the liner notes,[291] except where noted.

- Bruce Springsteen – lead vocals, lead and rhythm guitars (1–6, 8), harmonica (1), horn arrangement (2)

The E Street Band

- Roy Bittan – piano (tracks 2–4, 6–8), glockenspiel (1, 3), harpsichord (3, 6), organ (4, 6), Fender Rhodes piano (1), backing vocals (1)

- Clarence Clemons – saxophones (1–3, 5, 6, 8)

- Garry Tallent – bass guitar (1–6, 8)

- Max Weinberg – drums (1–4, 6, 8)

- Ernest Carter – drums (5)

- Danny Federici – organ (5), glockenspiel (5)[292]

- David Sancious – keyboards (5), Fender Rhodes piano (5)[292]

Additional musicians

- Mike Appel – backing vocals (1)

- Steven Van Zandt – backing vocals (1), horn arrangement (2)

- Randy Brecker – trumpet (2, 7), flugel horn (2)

- Michael Brecker – tenor saxophone (2)

- David Sanborn – baritone saxophone (2)

- Wayne Andre – trombone (2)

- Richard Davis – double bass (7)

- Suki Lahav – violin (8)

- Charles Calello – string arrangements and conductor (8)

Technical

- Bruce Springsteen – production

- Mike Appel – production

- Jon Landau – production (1–4, 6–8)

- Jimmy Iovine – engineering and mixing

- Thom Panunzio, Corky Stasiak, Dave Thoener, Ricke Delena, Angie Arcuri, Andy Abrams – engineering assistants

- Louis Lahav – engineering (5)

- Greg Calbi – mastering

- Paul Prestopino – maintenance

- John Berg, Andy Engel – album design

- Eric Meola – photography

Charts

[edit]| Chart (1975–76) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Australian Albums (Kent Music Report)[164] | 7 |

| Canadian Top Albums (RPM)[170] | 31 |

| Irish Albums (IRMA)[167] | 20 |

| Dutch Albums (Album Top 100)[165] | 7 |

| New Zealand Albums (RMNZ)[169] | 28 |

| Norwegian Albums (VG-lista)[168] | 26 |

| Swedish Albums (Sverigetopplistan)[166] | 7 |

| U.K. Albums Chart (OCC)[163] | 36 |

| U.S. (Billboard Top LPs & Tape)[161] | 3 |

| U.S. (Record World)[155] | 1 |

| Chart (1985) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| U.K. Albums Chart (OCC)[162] | 17 |

| Chart (2005) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Italian Albums (Musica e Dischi)[293] 30th anniversary edition |

41 |

| U.S. (Billboard 200)[161] | 18 |

Certifications and sales

[edit]| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Australia (ARIA)[294] | 2× Platinum | 140,000^ |

| Canada (Music Canada)[295] | 2× Platinum | 200,000^ |

| Finland (Musiikkituottajat)[296] | Gold | 25,000[296] |

| France (SNEP)[297] | Gold | 100,000* |

| Ireland (IRMA)[298] 30th Anniversary |

Gold | 7,500^ |

| Italy (FIMI)[299] sales since 2009 |

Gold | 25,000* |

| Netherlands (NVPI)[300] | Gold | 50,000^ |

| New Zealand (RMNZ)[301] | Platinum | 15,000^ |

| Spain (PROMUSICAE)[302] | Gold | 50,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[303] | Platinum | 300,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[304] Video – 30th Anniversary Edition |

Platinum | 50,000^ |

| United States (RIAA)[159] | 7× Platinum | 7,000,000‡ |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Other sources, including the Recording Industry Association of America, cite a release date of September 1, 1975.[154][158][159]

- ^ CBS was the international distributor of Columbia outside of the United States.[7]

- ^ Most sources say March 1975,[24][46][52] while others say February[53] and April.[51]

- ^ Randy Brecker also plays the intro on "Meeting Across the River".[65]

- ^ Springsteen further explored the themes of "Night" on Darkness on the Edge of Town.[66]

- ^ The writer William Ruhlmann has argued that Springsteen later explored a platonic but powerful friendship between two men in the Born in the U.S.A. track "Bobby Jean" (1984).[114]

- ^ Masur argues that live performances of the song in the late 1970s clarify that Terry is a woman.[128]

- ^ These photos were compiled and published in Meola's book Born to Run: The Unseen Photos (2006).[141]

- ^ Another shot was later used for the 2024 compilation album Best of Bruce Springsteen.[142]

- ^ CBS and Columbia reignited promotion for Springsteen after seeing the quote; one executive used the quote on posters for record stores.[156]

- ^ Born to Run achieved a new peak of number 17 in the U.K. in 1985.[162]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[196][197][198][199]

- ^ The November 18 performance was filmed and later released on the 30th Anniversary Edition of Born to Run in 2005.[217][111] The performance appeared as a separate live album, Hammersmith Odeon, London '75, in 2006.[218]

- ^ The December 31 show was later released as a live album, Tower Theater, Philadelphia 1975, in 2015.[219]

- ^ Springsteen could not record in a studio without a producer approved by Appel.[225]

- ^ In 1983, Appel sold his share back to Springsteen, giving Springsteen full ownership of his own music.[225]

- ^ E Street Band member Steven Van Zandt had acted alongside Gandolfini in the television series The Sopranos (1999–2007).[247]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[28][94][118][138][239][261]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[262][263][242][264][265][266]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Margotin & Guesdon 2020, p. 70.

- ^ Kirkpatrick 2007, p. 31.

- ^ a b c d e Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 71–72.

- ^ a b c d Dolan 2012, p. 108.

- ^ a b c Kirkpatrick 2007, p. 32.

- ^ Springsteen 2016, p. 194.

- ^ Margotin & Guesdon 2020, p. 20.

- ^ Eliot 1992, p. 116.

- ^ Dolan 2012, p. 102.

- ^ Springsteen 2016, p. 203.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Lifton, Dave (August 22, 2020). "Bruce Springsteen's 'Born to Run': A Track-by-Track Guide". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ a b Hiatt, Brian (August 24, 2020). "Bruce Springsteen on Making 'Born to Run': 'We Went to Extremes'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ Carlin 2012, p. 172.

- ^ Springsteen 2016, pp. 207–209.

- ^ a b c Carlin 2012, p. 174.

- ^ Guterman 2005, p. 65.

- ^ Masur 2010, p. 41.

- ^ a b c Dolan 2012, p. 107.

- ^ Masur 2010, p. 49.

- ^ a b c d e f Margotin & Guesdon 2020, p. 72.

- ^ Carlin 2012, pp. 175–177.

- ^ Dolan 2012, pp. 102–103.

- ^ a b c d Kirkpatrick 2007, p. 35.

- ^ a b c Lifton, Dave (August 25, 2015). "How Bruce Springsteen Finally Became a Star with 'Born to Run'". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on March 15, 2017. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- ^ a b Masur 2010, pp. 44–47.

- ^ a b c d e f g Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 86–89.

- ^ Masur 2010, p. 51.

- ^ a b c d e Moss, Charles (August 24, 2015). "Born to Run at 40: A short history of the album that turned Bruce Springsteen into America's biggest rock star". The Week. Archived from the original on March 16, 2017. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- ^ a b Springsteen 2016, p. 210.

- ^ a b Kirkpatrick 2007, p. 33.

- ^ Carlin 2012, pp. 186–187.

- ^ a b c d e f Gaar 2016, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Gaar 2016, p. 50.

- ^ a b Carlin 2012, pp. 182–184.

- ^ Dolan 2012, pp. 109–111.

- ^ a b c Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 90–91.

- ^ a b Dolan 2012, p. 113.

- ^ a b c d e Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 94–97.

- ^ Masur 2010, p. 44.

- ^ Dolan 2012, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Masur 2010, p. 48.

- ^ a b Kirkpatrick 2007, p. 34.

- ^ Carlin 2012, pp. 188–189.

- ^ Dolan 2012, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Masur 2010, pp. 52–53.

- ^ a b c d Carlin 2012, p. 194.

- ^ a b c d Kirkpatrick 2007, p. 37.

- ^ Carlin 2012, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Dolan 2012, pp. 104–105.

- ^ a b c Marsh 1981, p. 146.

- ^ a b c Masur 2010, p. 54.

- ^ a b Gaar 2016, p. 52.

- ^ Margotin & Guesdon 2020, p. 68.

- ^ Margotin & Guesdon 2020, p. 64.

- ^ Eliot 1992, p. 100.

- ^ Gaar 2016, pp. 52–53.

- ^ a b Dolan 2012, p. 123.

- ^ a b c d e Margotin & Guesdon 2020, p. 74.

- ^ Marsh 1981, p. 147.

- ^ Kirkpatrick 2007, pp. 37–38.

- ^ a b c Marsh 1981, pp. 149–150.

- ^ Masur 2010, p. 58.

- ^ Kirkpatrick 2007, p. 38.

- ^ a b Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 76–78.

- ^ a b c d e Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 92–93.

- ^ a b c d Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 82–83.

- ^ a b c d e f Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Carlin 2012, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Masur 2010, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Dolan 2012, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Carlin 2012, p. 196.

- ^ Masur 2010, pp. 51–52.

- ^ a b Masur 2010, p. 60.

- ^ Kirkpatrick 2007, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Springsteen 2016, p. 222.

- ^ a b c Margotin & Guesdon 2020, p. 75.

- ^ a b Kirkpatrick 2007, p. 39.

- ^ Carlin 2012, p. 195.

- ^ a b Carlin 2012, pp. 197–199.

- ^ a b Dolan 2012, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Bernstein, Jonathan (December 4, 2021). "Greg Calbi's Invisible Touch". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on January 17, 2024. Retrieved January 24, 2024.

- ^ a b Masur 2010, p. 62.

- ^ Dolan 2012, pp. 125–126.

- ^ Margotin & Guesdon 2020, p. 63.

- ^ a b c Gaar 2016, p. 53.

- ^ McCormick, Neil (October 22, 2020). "Springsteen's 40-Year Secret Is Out – and All Eyes Are on a Forgotten Rock Maverick". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved October 25, 2020.

- ^ Regev 2013, p. 67: pop rock.

- ^ Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 69–70: rock and roll, R&B, and folk-rock.

- ^ a b c d Carlin 2012, pp. 200–201.

- ^ a b Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 69–70.

- ^ a b c d "Born to Run by Bruce Springsteen". Classic Rock Review. September 17, 2015. Archived from the original on January 28, 2023. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ a b Kirkpatrick 2007, p. 36.

- ^ a b c d Zimny, Thom (director) (2005). Wings for Wheels: The Making of Born to Run (film). Thrill Hill Productions.

- ^ a b c d e f Ruhlmann, William. "Born to Run – Bruce Springsteen". AllMusic. Archived from the original on October 1, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ a b Masur 2010, pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b Fricke, David (January 21, 2009). "The Band on Bruce: Their Springsteen". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 1, 2009. Retrieved February 7, 2009.

- ^ Carlin 2012, p. 201.

- ^ Masur 2010, p. 128: Frank Rose.

- ^ a b Springsteen 2003, pp. 43–47.

- ^ Masur 2010, p. 114.

- ^ a b c d e Blum, Jordan (August 25, 2020). "45 Reasons We Still Love Bruce Springsteen's Born to Run". Consequence. Archived from the original on March 25, 2023. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Masur 2010, p. 65.

- ^ Masur 2010, p. 116.

- ^ a b Kirkpatrick 2007, p. 41.

- ^ Masur 2010, p. 110.

- ^ a b c Vigilla, Hubert (September 5, 2005). "Bruce Springsteen's Born to Run is a classic rock triumph". Treble. Archived from the original on November 15, 2022. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Masur 2010, p. 72.

- ^ a b c d Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 68–69.

- ^ a b Hermann, Veronika (2019). "Runaway American Dream: Nostalgia, Figurative Memory, and Autofiction in Stories of Born to Run". Interdisciplinary Literary Studies. 21 (1). Penn State University Park: Penn State University Press: 42–56. doi:10.5325/intelitestud.21.1.0042. JSTOR 10.5325/intelitestud.21.1.0042. S2CID 194349341.

- ^ Masur 2010, p. 115.

- ^ a b c d Richardson, Mark (November 18, 2005). "Bruce Springsteen Born to Run: 30th Anniversary Edition Album Review". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ Masur 2010, p. 109.

- ^ a b c Masur 2010, p. 100.

- ^ a b c d Ruhlmann, William. "'Backstreets' – Bruce Springsteen Song Review". AllMusic. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ Masur 2010, p. 66.

- ^ Masur 2010, p. 70.

- ^ a b Kirkpatrick 2007, p. 42.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Partridge, Kenneth (August 25, 2015). "Bruce Springsteen's 'Born to Run' Turns 40: Classic Track-by-Track Album Review". Billboard. Archived from the original on April 1, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ a b Gerard, James. "'Thunder Road' – Bruce Springsteen Song Review". AllMusic. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ Dolan 2012, p. 120.

- ^ Masur 2010, p. 71.

- ^ a b Ruhlmann, William. "'Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out' – Bruce Springsteen Song Review". AllMusic. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Kirkpatrick 2007, p. 43.

- ^ Masur 2010, p. 76.

- ^ Masur 2010, p. 75.

- ^ a b c Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Masur 2010, p. 78.

- ^ Masur 2010, p. 80.

- ^ Masur 2010, p. 83.

- ^ Ankeny, Jason. "'Born to Run' – Bruce Springsteen Song Review". AllMusic. Archived from the original on May 27, 2020. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ a b Carlin 2012, p. 202.

- ^ a b Masur 2010, pp. 87–88.

- ^ a b Masur 2010, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Kirkpatrick 2007, pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b c Masur 2010, pp. 91–93.

- ^ Kirkpatrick 2007, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Carlin 2012, pp. 202–203.

- ^ a b c Coffman, Tim (March 18, 2023). "Bruce Springsteen – 'Born to Run' album review". Far Out. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "The story behind Bruce Springsteen's Born To Run album artwork". Louder. July 20, 2020. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Masur 2010, p. 102.

- ^ Meola, Eric; Springsteen, Bruce (2006). Born to Run: The Unseen Photos. Insight Editions. ISBN 978-1-93378-409-0. Retrieved April 21, 2024 – via Google Books.

- ^ Strauss, Matthew (March 1, 2024). "Bruce Springsteen Announces New Greatest Hits Album". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on March 2, 2024. Retrieved March 2, 2024.

- ^ Masur 2010, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Lewis, Randy (February 13, 2014). "Bruce Springsteen on the Stratocaster". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 20, 2014.

- ^ "Readers Poll: The Best Album Covers of All Time". Rolling Stone. June 15, 2011. Archived from the original on November 29, 2016. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- ^ Kaye & Brewer 2008, p. xii.

- ^ a b Irwin, Corey (August 24, 2020). "Bruce Springsteen 'Born to Run' Album Cover Copycats". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on June 7, 2023. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Masur 2010, p. 148.

- ^ Carlin 2012, pp. 197–198.

- ^ a b c Carlin 2012, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Kirkpatrick 2007, pp. 39–40.

- ^ a b Fricke, David (June 4, 1987). "Live! Twenty Concerts that Changed Rock & Roll". Rolling Stone. No. 501. pp. 89–90.

- ^ Masur 2010, pp. 119–120.

- ^ a b Kirkpatrick 2007, p. 40.

- ^ a b c Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Carlin 2012, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Dolan 2012, p. 127.

- ^ a b Gaar 2016, p. 198.

- ^ a b c "American album certifications – Bruce Springsteen – Born to Run". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- ^ "Born to Run". Bruce Springsteen Official Website. Archived from the original on April 29, 2024. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band Chart History". Billboard. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ a b "Born to Run – Bruce Springsteen | Official Charts". Official Charts. Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on October 22, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ^ a b "Bruce Springsteen | full Official Chart History". Official Charts. Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on December 16, 2023.

- ^ a b Kent 1993, p. 289.

- ^ a b "Dutchcharts.nl – Bruce Springsteen – Born to Run" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ a b "Swedishcharts.com – Bruce Springsteen – Born to Run". Hung Medien. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ a b "GFK Chart-Track Albums: Week {{{week}}}, {{{year}}}". Chart-Track. IRMA. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ a b "Norwegiancharts.com – Bruce Springsteen – Born to Run". Hung Medien. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ a b "Charts.nz – Bruce Springsteen – Born to Run". Hung Medien. Retrieved December 20, 2021.

- ^ a b "Item Display – RPM – Top Albums/CDs". RPM. Vol. 24, no. 13. December 20, 1975. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ a b Carlin 2012, p. 210.

- ^ a b Dolan 2012, p. 128.

- ^ Dolan 2012, p. 132.

- ^ Masur 2010, p. 129.

- ^ a b Lifton, Dave (October 27, 2015). "Revisiting Bruce Springsteen's 'Time' and 'Newsweek' Covers". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on June 17, 2019. Retrieved August 22, 2023.

- ^ a b Kirkpatrick 2007, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Carlin 2012, p. 206.

- ^ a b c Edwards, Henry (October 5, 1975). "If There Hadn't Been a Bruce Springsteen, Then the Critics Would Have Made Him Up; The Invention of Bruce Springsteen". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Rockwell, John (October 24, 1975). "The Pop Life; 'Hype' and the Springsteen Case". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ Dolan 2012, p. 131.

- ^ a b Masur 2010, p. 133.

- ^ Masur 2010, p. 132.

- ^ Dolan 2012, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Carlin 2012, p. 207.

- ^ a b Masur 2010, pp. 134–135.

- ^ Dolan 2012, p. 130.

- ^ Clarke 1990, p. 1109.

- ^ Miller 1999, p. 325.

- ^ Masur, Louis P. (August 21, 2005). "The long run with Springsteen". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ Marcus, Greil (October 9, 1975). "Born to Run". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on July 23, 2014. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (September 22, 1975). "Christgau's Consumer Guide". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on May 25, 2014. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ a b c "Top Album Picks" (PDF). Billboard. September 6, 1975. p. 66. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 15, 2023. Retrieved August 17, 2023 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ a b Masur 2010, p. 125: Jon Pareles

- ^ a b c Masur 2010, pp. 127–128: Stephen Holden, Circus Raves

- ^ Masur 2010, p. 121: Newsweek, September 1, 1975

- ^ a b Masur 2010, pp. 126–127: David McGee

- ^ a b c d Lester Bangs, Creem: Masur 2010, pp. 124–125. Sawyers 2004, pp. 75–77

- ^ Watts, Michael (September 6, 1975). "'Born to Run'" (PDF). Melody Maker. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 16, 2023. Retrieved August 24, 2023 – via Cash Box magazine.

- ^ "Album Reviews: Pop Picks" (PDF). Cash Box. September 6, 1975. p. 20. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 16, 2023. Retrieved August 17, 2023 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ "Hits of the Week: Albums" (PDF). Record World. September 6, 1975. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 26, 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2023 – via worldradiohistory.com.

- ^ a b Gilbert, Jerry (September 13, 1975). "Bruce Springsteen: Born to Run (Columbia import)". Sounds. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023 – via Rock's Backpages.

- ^ Masur 2010, p. 129: Jay Cocks, Time.

- ^ Greene, Andy (October 27, 2015). "See Rare Bruce Springsteen Photos From 'Born to Run' Era". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on August 6, 2019. Retrieved August 6, 2019.

- ^ Hilburn, Robert (September 21, 1975). "Back-to-School Record Collection for Hard Times". Los Angeles Times. pp. 64–65. Archived from the original on August 19, 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Masur 2010, pp. 128–129: Joe Edwards, Aquarian

- ^ a b c Carr, Roy (September 6, 1975). "Bruce Springsteen: Born to Run (CBS Import)". NME. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023 – via Rock's Backpages.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (January 26, 1976). "Yes, There Is a Rock-Critic Establishment (But Is That Bad for Rock?)". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ Jahn, Mike (1975). "Bruce Springsteen: Born to Run (Columbia PC 33795)". High Fidelity. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023 – via Rock's Backpages.

- ^ "The 1975 Pazz & Jop Critics Poll". The Village Voice. December 29, 1975. Archived from the original on October 15, 2014. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (December 29, 1975). "It's Been a Soft Year for Hard Rock". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on October 15, 2014. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ Carlin 2012, pp. 210–211.

- ^ a b Carlin 2012, pp. 211–212.

- ^ a b Gaar 2016, p. 61.

- ^ Dolan 2012, pp. 130–131.

- ^ a b Carlin 2012, pp. 212–213.

- ^ Masur 2010, pp. 136–138.

- ^ a b c Clarke, Betty (November 17, 2005). "Bruce Springsteen, Born to Run – 30th Anniversary Edition". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 1, 2017.

- ^ Costa, Maddy (February 23, 2006). "Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band, Hammersmith Odeon London '75". The Guardian. Archived from the original on February 23, 2014. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- ^ "Download Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band December 31, 1975, Tower Theater, Upper Darby, PA MP3 and FLAC". Bruce Springsteen Live. 2014. Archived from the original on June 5, 2023. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ^ Carlin 2012, p. 213.

- ^ Dolan 2012, p. 144.

- ^ a b Kirkpatrick 2007, pp. 49–51.

- ^ Gaar 2016, p. 60.

- ^ Gaar 2016, pp. 61–62.

- ^ a b c d e f Margotin & Guesdon 2020, pp. 102–109.

- ^ a b Cameron, Keith (September 23, 2010). "Bruce Springsteen: 'People thought we were gone. Finished'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 2, 2022. Retrieved January 30, 2023.

- ^ Carlin 2012, p. 223.

- ^ Dolan 2012, p. 137.

- ^ Carlin 2012, p. 226.

- ^ Dolan 2012, pp. 146–149.

- ^ Gaar 2016, pp. 68–70.

- ^ Dolan 2012, pp. 149–150.

- ^ Carlin 2012, p. 245.

- ^ Gaar 2016, p. 71.

- ^ a b Kahn, Ashley (November 10, 2005). "Springsteen Looks Back On 'Born to Run'". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on September 30, 2023. Retrieved September 30, 2023.

- ^ Dolan 2012, pp. 133–134.

- ^ a b c "Top 100 '70s Rock Albums". Ultimate Classic Rock. October 26, 2022. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ^ Ruhlmann, William. "Bruce Springsteen Bio | Bruce Springsteen Career". MTV. Archived from the original on November 8, 2016. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ^ a b Kirkpatrick 2007, p. 45.

- ^ Hilburn 1985, p. 68: The Sun Sessions and Highway 61 Revisited.

- ^ a b Carlin 2012, p. 203.

- ^ a b Lifton, Dave (July 29, 2015). "Bruce Springsteen Albums Ranked Worst to Best". Ultimate Classic Rock. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ Greene, Andy (May 8, 2008). "Bruce Springsteen Performs Two Full LPs at Rare Theater Show". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on November 8, 2016. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ^ Greene, Andy (July 28, 2009). "Bruce Springsteen Playing All of 'Born to Run' in Chicago". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on December 23, 2011. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- ^ "Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band announce hiatus". Consequence of Sound. September 16, 2009. Archived from the original on September 12, 2013. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ^ Goldstein, Stan (July 31, 2013). "Bruce Springsteen's Wrecking Ball tour: Stats and tidbits as European leg ends". NJ.com. Archived from the original on November 8, 2016. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ^ a b Danton, Eric R. (June 21, 2013). "Bruce Springsteen Dedicates 'Born to Run' to James Gandolfini Onstage". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on June 24, 2013. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- ^ a b Masur 2010, pp. 111–112.

- ^ a b Zeitz, Joshua (August 24, 2015). "How Bruce Springsteen's Born to Run Captured the Decline of the American Dream". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on November 21, 2023. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ a b c "The 100 Best Albums of the 1970s". Paste. January 7, 2020. Archived from the original on August 7, 2023. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ^ Masur 2010, pp. 112–113.

- ^ a b Kot, Greg (August 23, 1992). "The Recorded History of Springsteen". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (1981). "Consumer Guide '70s: S". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the Seventies. Boston: Ticknor & Fields. ISBN 0-89919-026-X. Archived from the original on April 13, 2019. Retrieved March 13, 2019 – via robertchristgau.com.

- ^ Larkin 2011, p. 1,957.

- ^ Graff 1996, pp. 638–639.

- ^ Bailie, Stuart; Staunton, Terry (March 11, 1995). "Ace of boss". New Musical Express. pp. 54–55.

- ^ Williams, Richard (December 1989). "All or Nothing: The Springsteen back catalogue". Q. No. 39. p. 149. Archived from the original on February 12, 2024. Retrieved February 12, 2024 – via Rock's Backpages.

- ^ Sheffield 2004, pp. 771–773.

- ^ Freeman, Channing (June 22, 2011). "Bruce Springsteen Born To Run > Staff Review". Sputnikmusic. Archived from the original on October 1, 2023. Retrieved June 29, 2011.

- ^ Hull, Tom (October 29, 2016). "Streamnotes (October 2016)". Tom Hull – on the Web. Archived from the original on July 4, 2020. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- ^ Gertsenzang, Peter (August 25, 2015). "How Bruce Springsteen Made 'Born To Run' an American Masterpiece". The Observer. Archived from the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ a b Taub, Matthew (November 8, 2022). "Bruce Springsteen: every album ranked in order of greatness". NME. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ Hyden, Steven (November 11, 2022). "Every Bruce Springsteen Studio Album, Ranked". Uproxx. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ a b Hann, Michael (May 30, 2019). "Bruce Springsteen's albums – ranked!". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 31, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ Shipley, Al (November 11, 2022). "Every Bruce Springsteen Album, Ranked". Spin. Archived from the original on February 4, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ McCormick, Neil (October 24, 2020). "Bruce Springsteen: all his albums ranked, from worst to best". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on August 23, 2023. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ Masur, Louis (September 22, 2009). "Born to Run: The groundbreaking Springsteen album almost didn't get released". Slate. Archived from the original on August 10, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ Thomas, Lou (2007). "Review of Bruce Springsteen – Born to Run". BBC Music. Archived from the original on October 19, 2016. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ^ Klinger, Eric; Mendelsohn, Jason (June 8, 2020). "Counterbalance 18: Bruce Springsteen – Born to Run". PopMatters. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ a b Christgau, Robert (January–February 2006). "Re-Run: Bruce Springsteen Born to Run (30th Anniversary Edition)". Blender. Posted at "Re-Run". robertchristgau.com. Robert Christgau. Archived from the original on November 5, 2011. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

- ^ Stephens, Christopher John (August 25, 2020). "Bruce Springsteen's 'Born to Run' Brought Elegiac Depth and Youthful Romanticism to Heartland Rock". PopMatters. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 10, 2023.

- ^ a b Beviglia, Jim (August 28, 2023). "Classic Rock Gems: 10 Albums That Shaped the 1970s Music Landscape". American Songwriter. Archived from the original on August 29, 2023. Retrieved August 29, 2023.

- ^ a b Masur 2010, p. 147.

- ^ DeCurtis, Anthony; Coleman, Mark (August 27, 1987). "The Best 100 Albums of the Last Twenty Years". Rolling Stone. No. 507. p. 45.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. 2012. Archived from the original on July 4, 2019. Retrieved September 23, 2019.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. September 22, 2020. Archived from the original on June 20, 2023. Retrieved August 8, 2023.

- ^ "The Greatest: 100 Greatest Albums of Rock & Roll". The Greatest. VH1. Archived from the original on October 1, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2007.