Zachary Taylor: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 96.4.201.19 to last version by Kangaru99 (HG) |

|||

| Line 116: | Line 116: | ||

===Death=== |

===Death=== |

||

The cause of Zachary Taylor's death is not well understood. On [[July 4]], [[1850]], Taylor consumed a snack of milk and cherries at an [[Independence Day]] celebration. Upon his sudden death, five days later on [[July 9]]th,<ref>[http://www.whitehouse.gov/history/presidents/zt12.html "Biography of Zachary Taylor"] from [[The White House]]</ref> the cause was listed as [[ |

The cause of Zachary Taylor's death is not well understood. On [[July 4]], [[1850]], Taylor consumed a snack of milk and cherries at an [[Independence Day]] celebration. Upon his sudden death, five days later on [[July 9]]th,<ref>[http://www.whitehouse.gov/history/presidents/zt12.html "Biography of Zachary Taylor"] from [[The White House]]</ref> the cause was listed as [[choking]]. |

||

In the late 1980's, author [[Clara Rising]] theorized that Taylor was murdered by poison and was able to convince Taylor's closest living relative, as well as the Jefferson Co., KY [[Coroner]], [[Dr. Richard Greathouse]], to order an exhumation. On June 17, 1991 Taylor's remains were exhumed from the vault at the [[Zachary Taylor National Cemetery]], in [[Louisville, KY]]. The remains were then transported to the Office of the [[Kentucky]] Chief Medical Examiner, [[Dr. George Nichols]]. Nichols, joined by [[Dr. William Maples]], a [[forensic anthropologist]] at the [[University of Florida]] in [[Gainesville, Florida]], removed the top of the lead coffin liner to reveal remarkably well preserved human remains that were immediately recoginzable as those of President Taylor. Radiological studies were conducted of the remains before small samples of hair, fingernail and other tissues were removed. Thomas Secoy of the [[Department of Veterans Affairs]], as well as a direct descendant of [[Lewis Cass]], insured that only those samples required for testing were removed and that the coffin was resealed. The remains were then returned to the cemetery and received appropriate honors at reinterment. The samples were sent to [[Oak Ridge National Laboratory]], where [[neutron activation analysis]] revealed traces of [[arsenic]] at levels several hundred times less than necessary for poisoning to have occurred. <ref>[http://www.ornl.gov/info/ornlreview/rev27-12/text/ansside6.html "President Zachary Taylor and the Laboratory: Presidential Visit from the Grave"] from [[Oak Ridge National Laboratory]]</ref> |

In the late 1980's, author [[Clara Rising]] theorized that Taylor was murdered by poison and was able to convince Taylor's closest living relative, as well as the Jefferson Co., KY [[Coroner]], [[Dr. Richard Greathouse]], to order an exhumation. On June 17, 1991 Taylor's remains were exhumed from the vault at the [[Zachary Taylor National Cemetery]], in [[Louisville, KY]]. The remains were then transported to the Office of the [[Kentucky]] Chief Medical Examiner, [[Dr. George Nichols]]. Nichols, joined by [[Dr. William Maples]], a [[forensic anthropologist]] at the [[University of Florida]] in [[Gainesville, Florida]], removed the top of the lead coffin liner to reveal remarkably well preserved human remains that were immediately recoginzable as those of President Taylor. Radiological studies were conducted of the remains before small samples of hair, fingernail and other tissues were removed. Thomas Secoy of the [[Department of Veterans Affairs]], as well as a direct descendant of [[Lewis Cass]], insured that only those samples required for testing were removed and that the coffin was resealed. The remains were then returned to the cemetery and received appropriate honors at reinterment. The samples were sent to [[Oak Ridge National Laboratory]], where [[neutron activation analysis]] revealed traces of [[arsenic]] at levels several hundred times less than necessary for poisoning to have occurred. <ref>[http://www.ornl.gov/info/ornlreview/rev27-12/text/ansside6.html "President Zachary Taylor and the Laboratory: Presidential Visit from the Grave"] from [[Oak Ridge National Laboratory]]</ref> |

||

Revision as of 17:36, 5 September 2008

Zachary Taylor | |

|---|---|

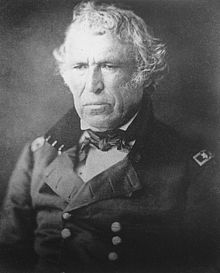

Daguerreotype of President Taylor taken in 1849 by Matthew Brady | |

| 12th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1849[1] – July 9, 1850 | |

| Vice President | Millard Fillmore |

| Preceded by | James K. Polk |

| Succeeded by | Millard Fillmore |

| Personal details | |

| Born | November 24, 1784 Barboursville, Virginia |

| Died | July 9, 1850 (aged 65) Washington, D.C. |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Whig |

| Spouse | Margaret Smith Taylor |

| Occupation | Soldier (General) |

| Signature | |

| Nickname(s) | Old Rough and Ready |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1808-1848 |

| Rank | Major General |

| Battles/wars | War of 1812 Black Hawk War Second Seminole War Mexican-American War *Battle of Monterrey *Battle of Buena Vista |

Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was an American military leader and the twelfth President of the United States. Known as "Old Rough and Ready," Taylor had a 40-year military career in the U.S. Army, serving in the War of 1812, Black Hawk War, and Second Seminole War before achieving fame leading U.S. troops to victory at several critical battles of the Mexican-American War. A Southern slaveholder who opposed the spread of slavery to the territories, he was uninterested in politics but was recruited by the Whig Party as their nominee in the 1848 presidential election. In the election, Taylor defeated the Democratic nominee, Lewis Cass, and became the second U.S. president never to hold any prior office (George Washington had been the first). Taylor was also the last southerner to be elected president until Woodrow Wilson. (Andrew Johnson became president through succession).

As president, Taylor urged settlers in New Mexico and California to bypass the territorial stage and draft constitutions for statehood, setting the stage for the Compromise of 1850.

Taylor died of acute gastroenteritis just 16 months into his term. Vice President Millard Fillmore then became President.

Early life

Taylor was born on November 24, 1784, in a log cabin in Montebello, near Barboursville in Orange County, Virginia.

He was the third of nine children of Colonel Richard Lee Taylor and Sarah Strother. James Madison was a second cousin and Robert E. Lee was a third cousin once removed (through Colonel Richard Lee the Immigrant). In his infancy, Taylor's family moved to Jefferson County, Kentucky, now Jefferson County (Louisville Metro) in Kentucky, where Taylor grew up on a plantation called "Springfield", now called the Zachary Taylor House. He was known as "Little Zack" and was educated by private tutors. He was a descendant of King Edward I of England, as well as Mayflower passengers Isaac Allerton and William Brewster.

Taylor met Margaret Mackall Smith of Maryland in early 1810, and they were married on June 21, 1810. They had one son and five daughters, two of whom died in infancy.

- Ann Mackall Taylor (April 9, 1811 - December 2, 1875)

- Sarah Knox "Knoxie" Taylor (March 6, 1814 - September 15, 1835)

- Octavia Pannill Taylor (August 16, 1816 - July 8, 1820)

- Mary Smith Taylor (July 27, 1819 - October 22, 1820)

- Mary Elizabeth "Betty" Taylor (April 20, 1824 - July 25, 1909)

- Richard "Dick" Taylor (January 27, 1826 - April 12, 1879), Confederate States Army General

Military career

On May 3, 1808, Taylor joined the U.S. Army, receiving a commission as a first lieutenant of the Seventh Infantry Regiment from his cousin James Madison. He was ordered west into Indiana Territory, taking command at the Battle of Fort Harrison; he was promoted to captain in November 1810.

During the War of 1812, Taylor became known as a talented military commander. Assigned to command Fort Harrison on the Wabash River, at the northern edge of present-day Terre Haute, Indiana, he successfully commandeered a small force of soldiers and civilians to stave off a British-inspired attack by about 500 Native Americans between September 4 and September 15. The Battle of Fort Harrison, as it became known, has been referred to as the "first American land victory of the War of 1812." Taylor received a brevet promotion to major on October 31, 1812. Taylor was promoted to lieutenant colonel on April 20, 1819, and colonel on April 5, 1832.

Taylor served in the Black Hawk War (May-August 1832) and the Second Seminole War (1835-1842). During the Seminole War, Taylor fought at the Battle of Lake Okeechobee and received a brevet promotion to brigadier general in January 1838. It was here he gained his nickname "Old Rough and Ready" for his rumpled clothes and wide-brimmed straw hat. On May 15, 1838, Taylor was promoted commanding general of all U.S. forces in Florida.

James K. Polk sent the Army of Occupation under Taylor's command to the Rio Grande in 1846. After the Thornton Affair, an incident in disputed territory in which Mexician troops killed and captured a squadron of the 2nd dragoons, Polk urged Congress to declare the Mexican-American War. In that conflict Taylor won an important victory at the Battle of Monterrey and led the U.S. army at the Battle of Buena Vista, becoming a national hero.

Polk kept Taylor in Northern Mexico, disturbed by his informal habits of command, particularly his decision to negotiate a ceasefire at Monterrey against Polk's wishes, and his affiliation with the Whig Party. He sent an expedition under General Winfield Scott to capture Mexico City. Taylor, incensed, thought that "the battle of Buena Vista opened the road to the city of Mexico and the halls of Montezuma, that others might revel in them."

Election of 1848

Taylor received the Whig nomination for President in 1848. Millard Fillmore of Cayuga County, New York was chosen for the Vice Presidential nominee. Like many other army officers, Taylor was nonpolitical and had never voted. His homespun ways and his status as a war hero were political assets. Taylor defeated Lewis Cass, the Democratic candidate, and Martin Van Buren, the Free Soil candidate.

To the astonishment of Whigs, Taylor ignored their platform, as historian Michael Holt explains:

Taylor was equally indifferent to programs Whigs had long considered vital. Publicly, he was artfully ambiguous, refusing to answer queries about his views on banking, the tariff, and internal improvements. Privately, he was more forthright. The idea of a national bank "is dead, and will not be revived in my time." In the future the tariff "will be increased only for revenue"; in other words, Whig hopes of restoring the protective tariff of 1842 were vain. There would never again be surplus federal funds from public land sales to distribute to the states, and internal improvements "will go on in spite of presidential vetoes." In a few words, that is, Taylor pronounced an epitaph for the entire Whig economic program.[2]

Presidency

Policies

From left to right: William B. Preston, Thomas Ewing, John M. Clayton, Zachary Taylor, William M. Meredith, George W. Crawford, Jacob Collamer and Reverdy Johnson, (1849).

Although Taylor had subscribed to Whig principles of legislative leadership, he was not inclined to be a puppet of Whig leaders in Congress. He ran his administration in the same rule-of-thumb fashion with which he had fought Native Americans.

Under Taylor's administration, the United States Department of the Interior was organized, although the legislation authorizing the Department had been approved on President Polk's last day in office. He appointed former Treasury Secretary Thomas Ewing the first Secretary of the Interior.

The Compromise of 1850

The slavery issue dominated Taylor's short term. Although he owned slaves, he took a moderate stance on the territorial expansion of slavery, angering fellow Southerners. He told them that if necessary to enforce the laws, he personally would lead the Army. Persons "taken in rebellion against the Union, he would hang ... with less reluctance than he had hanged deserters and spies in Mexico." He never wavered. Henry Clay then proposed a complex Compromise of 1850. Taylor died as it was being debated. (The Clay version failed but another version did pass under the new president, Millard Fillmore.)

Administration and Cabinet

| The Taylor cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Zachary Taylor | 1849–1850 |

| Vice President | Millard Fillmore | 1849–1850 |

| Secretary of State | John M. Clayton | 1849–1850 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | William M. Meredith | 1849–1850 |

| Secretary of War | George W. Crawford | 1849–1850 |

| Attorney General | Reverdy Johnson | 1849–1850 |

| Postmaster General | Jacob Collamer | 1849–1850 |

| Secretary of the Navy | William B. Preston | 1849–1850 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Thomas Ewing, Sr. | 1849–1850 |

Death

The cause of Zachary Taylor's death is not well understood. On July 4, 1850, Taylor consumed a snack of milk and cherries at an Independence Day celebration. Upon his sudden death, five days later on July 9th,[3] the cause was listed as choking.

In the late 1980's, author Clara Rising theorized that Taylor was murdered by poison and was able to convince Taylor's closest living relative, as well as the Jefferson Co., KY Coroner, Dr. Richard Greathouse, to order an exhumation. On June 17, 1991 Taylor's remains were exhumed from the vault at the Zachary Taylor National Cemetery, in Louisville, KY. The remains were then transported to the Office of the Kentucky Chief Medical Examiner, Dr. George Nichols. Nichols, joined by Dr. William Maples, a forensic anthropologist at the University of Florida in Gainesville, Florida, removed the top of the lead coffin liner to reveal remarkably well preserved human remains that were immediately recoginzable as those of President Taylor. Radiological studies were conducted of the remains before small samples of hair, fingernail and other tissues were removed. Thomas Secoy of the Department of Veterans Affairs, as well as a direct descendant of Lewis Cass, insured that only those samples required for testing were removed and that the coffin was resealed. The remains were then returned to the cemetery and received appropriate honors at reinterment. The samples were sent to Oak Ridge National Laboratory, where neutron activation analysis revealed traces of arsenic at levels several hundred times less than necessary for poisoning to have occurred. [4]

Despite these findings, assassination theories have not been entirely put to rest. Michael Parenti devoted a chapter in his controversial 1999 book History as Mystery[5] to what he called "The Strange Death of Zachary Taylor". In it he speculated that Taylor was assassinated and that his autopsy was botched.

He took a few sips of iced milk, again adding to the possibility of cholera. He lapsed again into unconsciousness and died on July 9, 1850.

Taylor is buried in Louisville, Kentucky, at what is now the Zachary Taylor National Cemetery.

Surviving family

- Taylor's son Richard became a Confederate Lieutenant General, while his daughter Sarah Knox Taylor (1814–1835) had married future President of the Confederate States Jefferson Davis three months before her death of malaria.

- Taylor's brother, Joseph Pannill Taylor, was a Brigadier General in the Union Army during the Civil War. (Joseph P. Taylor's son Joseph Hancock Taylor was a US Colonel in the Civil War and was also a son-in-law of Union General Montgomery C. Meigs).

- Taylor's niece Emily Ellison Taylor was the wife of Confederate General Lafayette McLaws.

- Ann Taylor's son John Taylor Wood, a U.S. Navy officer, defected to the Confederate side and later fled to Canada during the Civil War; his great-grandson Zachary Taylor Wood was Acting RCMP Commssioner, great-grandson Lieutenant Charles Carroll Wood died from wounds suffered during the Anglo Boer War, great-great-grandson Stuart Taylor Wood was Commissioner of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police and great-great-great-grandsons (Cst. Herschel Wood and Supt.(Ret) John Taylor Wood served in the RCMP.

References

- ^ *Taylor's term of service was scheduled to begin on March 4, 1849, but as this day fell on a Sunday, Taylor refused to be sworn in until the following day. Vice President Millard Fillmore was also not sworn in on that day. Most scholars believe that according to the U.S. Constitution, Taylor's term began on March 4, regardless of whether he had taken the oath or not.

- ^ Holt 1999 p 272

- ^ "Biography of Zachary Taylor" from The White House

- ^ "President Zachary Taylor and the Laboratory: Presidential Visit from the Grave" from Oak Ridge National Laboratory

- ^ "Parenti", "Michael" (1999). "History as Mystery". "City Light Books". p. 304. ISBN 9780872863576.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

Further reading

- Bauer, Jack K. Zachary Taylor: Soldier, Planter, Statesman of the Old Southwest. Louisiana State University Press: 1993. ISBN 0-8071-1851-6

- Hamilton, Holman. Zachary Taylor: Soldier of the Republic (1941) vol 1

- Hamilton, Holman. Zachary Taylor: Soldier in the White House (1951) vol 2

- Michael F. Holt; The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party: Jacksonian Politics and the Onset of the Civil War. (1999)

- Smith, Elbert B. The Presidencies of Zachary Taylor and Millard Fillmore. University Press of Kansas: 1988. ISBN 0-7006-0362-X.

- List of United States Presidents who died in office

External links

- Extensive essay on Zachary Taylor and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady from the Miller Center of Public Affairs

- White House Biography

- Biography by Appleton's and Stanley L. Klos

- Zachary Taylor State of the Union Address

- Zachary Taylor letters from 1846-1848

- Medical and Health history of Zachary Taylor

- Photo of grave of President Zachary Taylor, with GPS coordinates

- General Taylor's letters : letter of Gen. Taylor to Gen Gaines; Secretary Marcy's reprimand of Gen. Taylor; and Gen. Taylor's reply; with the fable alluded to annexed

{{subst:#if:Taylor, Zachary|}}

[[Category:{{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1784}}

|| UNKNOWN | MISSING = Year of birth missing {{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1850}}||LIVING=(living people)}}

| #default = 1784 births

}}]] {{subst:#switch:{{subst:uc:1850}}

|| LIVING = | MISSING = | UNKNOWN = | #default =

}}

- Living people

- 1850 deaths

- Presidents of the United States

- Whig Party (United States) presidential nominees

- United States presidential candidates, 1848

- United States Whig Party

- Defenders of slavery

- United States Army generals

- People of the Black Hawk War

- American military personnel of the Mexican-American War

- People of the Seminole Wars

- American people of the War of 1812

- History of the United States (1849–1865)

- Congressional Gold Medal recipients

- American Episcopalians

- People from Louisville, Kentucky

- Kentucky politicians

- Virginia politicians

- Americans of British descent

- Cause of death disputed

- Deaths from infectious disease

- People from Albemarle County, Virginia

- People from Orange County, Virginia