2003 La Paz riots

| Black February | |||

|---|---|---|---|

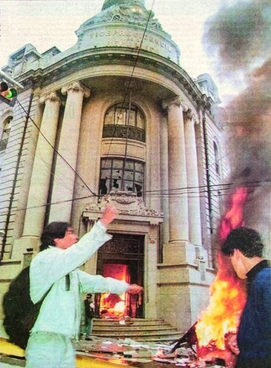

The Vice Presidency ablaze after having been vandalized by a riotous mob on 12 February 2003. | |||

| Date | 12–13 February 2003 | ||

| Location | La Paz, Bolivia | ||

| Caused by | Government tax reform proposal | ||

| Goals |

| ||

| Methods | Labor and police strikes, protests, demonstrations, and riots | ||

| Resulted in | Withdrawal of tax reform proposal | ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | 31 | ||

| Injuries | 268 | ||

The 2003 La Paz riots, commonly referred to as Black February (Spanish: Febrero Negro), was a period of civil unrest in La Paz, Bolivia, that took place between 12 and 13 February 2003. The riots were instigated by the imposition of a progressive salary tax—dubbed the impuestazo—aimed at meeting the International Monetary Fund's goal of reducing the country's fiscal deficit from 8.7% of GDP to 5.5%. The legislation mobilized a diverse array of groups against the proposal, including business sectors, trade unions, and university students.

The culmination of public unrest came when the National Police Corps mutinied against the government, leading to violent armed confrontations between police and the Army. On the second day of rioting, the government and police reached an agreement, and law enforcement quelled the unrest, by which time mobs had stoned the Palacio Quemado, set the Vice President's Office and the Ministry of Finance on fire, and attacked other public and municipal buildings. The official death toll was listed at thirty-one deaths and 268 injured, with the Organization of American States attributing all responsibility for the social upheaval to the National Police. A total of nineteen people were charged for the deaths caused, and the trial against them was installed in 2008. However, the legal process has since stalled; as of 2024, the trial has not yet been initiated.

Background

Starting in 1998, the Bolivian economy—characterized by a period of slow growth since 1986—entered into a slowdown phase induced by external troubles: a deterioration in terms of trade and the reversal in capital flows.[1] By the end of 2002, Bolivia, entering its fifth year of recession, faced a dire financial crisis: unemployment lay at 7.7%, GDP growth that year measured just 2.5%—well below the projected 8%—and external debt had reached 54.2% of GDP.[2] Most urgently, the country's fiscal deficit had skyrocketed from 3.3% of national income in 1997 to 8.7% in 2002. The latter factor prompted the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to demand that the Bolivian government cut its deficit to 5.5% of GDP. Such an undertaking necessitated a cut of US$250 million, 8% of the national budget. Failure to comply would have led the IMF to withdraw a long-term lending agreement. Without such an agreement, the Bolivian government faced the loss of not only Fund loans but also millions of dollars in foreign aid from Denmark, Germany, and Sweden.[3]

Following the events of February, the IMF stood its ground on the claim that the Bolivian government had fully agreed with the 5.5% target. However, Carlos Mesa—the then-vice president—stated that the government had told IMF officials that the budget cuts required to meet their goal were too drastic. Nonetheless, according to National Budget Director Edwin Aldunate, the IMF stood firm on the stated 5.5%, rejecting Bolivia's counteroffer to aim for 6.5%, despite being warned of the "serious social problems" the policies required to reach the organization's target could cause.[3]

In order to meet the IMF's demands, the government first set its sights on foreign oil producers, developing a taxation plan that would have generated up to US$160 million per year. However, this proposal was quickly shelved by President Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada, who feared that it would harm the country's ability to project a stable image to foreign investors. Instead, the president and his advisers agreed on a second proposal, a progressive income tax targeting the wealthiest 4% of the population, generating US$20 million per year. Given the relatively low amount of revenue this would generate, it was agreed to expand the tax to all individuals earning twice the national minimum wage.[4] In a speech delivered to the nation on the evening of 9 February 2003, President Sánchez de Lozada presented to Congress his fiscal austerity proposal within the framework of the 2003 General Budget of the Nation. With a focus on bolstering the economy and creating new jobs, the legislation projected a 25% increase in public investment—totaling some US$1 billion—a 2.45% increase in the minimum wage from Bs430 to Bs440.5—just over US$58—and a 0.5% reduction in consumption and transaction taxes. Further, the project proposed a 10% reduction in the bureaucratic expenses of the State: the central government, legislature, and judiciary. By doing this, Sánchez de Lozada hoped to release Bs280 million back into the economy.[5][6] The controversy arose in the plan's imposition of a wage tax beginning with those earning more than Bs880 (US$116) per month and increasing incrementally until it reached 12.5%.[5] As reported by Los Tiempos, the measure would have affected the wages of 500,000 workers, amounting to 5% of the population and around 25% of the salaried population.[6][7] For those in the lowest income bracket, such as nurses, police, and teachers, the tax hike equated to two additional dollars per month or enough to buy food for three days.[8]

Black February

General strikes

The president's tax announcement was near-unanimously repudiated by the general public, with businessmen, opposition political parties, and trade unions all threatening to mobilize in protest of the impuestazo.[9] Deputy Evo Morales—leader of the opposition and head of the cocalero trade unions—decried Sánchez de Lozada's tax proposal as an attempt to "unload the economic crisis on the backs of the people".[10] The People's General Staff—a consortium of social organizations opposed to the government of which Morales held membership—announced mobilizations in Cochabamba against the tax. As did the Bolivian Workers' Center (COB), which broke off social security negotiations it was carrying out with the government, declaring a twenty-four-hour general strike. For its part, the Unified Syndical Confederation of Rural Workers of Bolivia (CSUTCB) proposed an open "revolt" against the government in coordination with other trade union organizations.[9] Business interests also opposed the bill, deeming it harmful to the economy by reducing consumption, increasing unemployment, and promoting the informal economy, which evades tax payments. In an emergency meeting, the Confederation of Private Entrepreneurs of Bolivia (CEPB) requested an urgent meeting with Sánchez de Lozada to negotiate a reversal of the president's tax project.[5][9] Sánchez de Lozada stood firm on his stance, justifying that any other budget plan would be infeasible without "endangering the stability of our economy ... If a budget like this is not approved, [Bolivia] will go into economic collapse".[11]

The announced tax was also a topic of discussion among the rank and file officers of the National Police Corps (PN), as their Bs880 monthly salaries stood to be directly affected.[12] The majority Aymara police force, characterized by a respect for community decision-making where resolutions are final, resolved to oppose the government's tax reform bill.[13] At the center of these discussions was the Special Security Group (GES)[a] under the command of Major David Vargas. Vargas had a history of aiding and abetting acts considered "seditious" by the government, having previously participated in the so-called Cochabamba Water War just under three years prior, though he never faced legal repercussions.[15] The GES demanded a 40% increase in police wages.[16] Additionally, they sought a modification to the tax bill so that it would only apply to the most affluent sectors of society, those earning the equivalent of $660 per month. If their demands were met, the officers pledged to cease protesting. Although Minister of Government Alberto Gasser had publicly stated that the tax bill was "non-negotiable", he did nonetheless meet with Police High Command the following day.[13]

Police mutiny

Gasser arrived at GES headquarters at 6 a.m. on the morning of 12 February, where he told Vargas and other senior officers that the tax could not be withdrawn due to the government's commitment to the IMF.[13] By that point, uniformed and plainclothes police officers from various units had begun to congregate around the headquarters, located half a block from the Plaza Murillo, where the Palacio Quemado—the presidential palace—and other government institutions were located. Throughout the morning, police in and around the capital abandoned their posts, gathering near the Plaza Murillo and GES headquarters armed with weapons and riot control equipment. They were joined by cadets bused in from the National Police Academy as well as firefighters and a small amount of retirees. Some officers positioned themselves on the roof of the GES and from there made their way to the adjacent Foreign Ministry building.[b][14]

At 10 a.m., about 100 police officers began marching through the plaza itself, shouting their demands at the windows of the Palacio Quemado, where President Sánchez de Lozada, Vice President Mesa, and the cabinet had convened an emergency meeting the hour prior.[c][13] After a brief discussion between the president and his ministers, it was resolved not to give in to the PN's demands but to instead attempt to negotiate with Vargas and his mutineers. Sánchez de Lozada delegated this difficult task to his presidency, government, and defense ministers: Carlos Sánchez Berzaín, Alberto Gasser, and Freddy Teodovich, respectively.[17] Shortly after 10:30 a.m., the president got into contact with US Treasury Secretary John W. Snow to request US$120 million in aid in order to add some flexibility to possible amendments to the tax bill. Snow offered US$15 million, an amount Sánchez de Lozada found insulting and unacceptable. Exasperated, the president responded, in perfect English, that with that he "couldn't even afford to pay for the cigars he smoked" and hung up.[7] Shortly thereafter, the palace chief of security instructed everyone to move to the third floor. As recounted by Mesa, the conversation shifted focus to macroeconomics "in an unspoken intention to separate from the dramatic reality".[7]

Student protests

Outside the Palacio Quemado, the situation was rapidly deteriorating. Between 10 a.m. and 11 a.m., students from the Ayacucho School abandoned their campus to join the protests in the plaza but were repelled on the corner of Ayacucho and Comercio streets by crowd control units from the Police Academy, who used tear gas to disperse them. However, they later reconvened, making their way towards the Palacio Quemado and forcing the policemen to retreat to the Legislative Palace. A small contingent of soldiers attempted to disperse the students but was fired on with tear gas by PN officers. Lacking gas masks, the soldiers withdrew into the palace, leaving the building's exterior unguarded. Given the lack of security, the students began stoning the palace's façade, shattering windows on the ground floor and up to the second floor.[14] In an attempt to protect the building, palace guards fired tear gas at the students. According to Vargas, the tear gas, which reached police headquarters, was taken as an act of provocation, causing the police to fire back. By this point, an army contingent about a thousand strong moved in to occupy the plaza, commencing a standoff between soldiers and police.[13]

Eruption of hostilities

Army units continued to take up positions in and around the Plaza Murillo and Palacio Quemado, maintaining formation in the face of a growing crowd of protesting police and civilians, who levied shouts, obscenities, and tear gas. Elsewhere, the military occupied the corner of Comercio and Socabaya streets and began advancing north along Bolívar Street towards Ballivián Street, where another group of protesters had gathered. Police responded by lobbing tear gas, causing the army to retreat south and take up defensive positions around the Legislative Palace. At one point, a 17-year-old PN firefighter, Julián Huáscar Sánchez, was shot in or near the eye by a rubber bullet. Despite surviving the initial shot, he later died from his injuries, becoming one of the first casualties of the deadly events that soon unfolded.[14][18] Major Vargas subsequently reported to local media that the PN would be executing "Plan Red", warning citizens to stay in their homes. Privately, however, he resumed dialogue with Brigadier General Hugo Tellería and Defense Minister Freddy Teodovich in a meeting mediated by Sacha Llorenti of the Permanent Assembly of Human Rights of Bolivia (APDHB). A short ceasefire was reached in order to facilitate further negotiations. The military agreed to withdraw its forces from the plaza center, and in exchange, the police would halt their demonstrations.[14]

At some point during the military withdrawal, around 2 p.m., the situation escalated, and live ammunition was exchanged between the military and national police. Which side shot first is unclear, with police claiming it was the military.[13] The official report of events lays blame on the police, stating that a contingent of officers arrived on Comercio Street brandishing weapons as they exited their vehicles. As the soldiers retreated to Ayacucho Street, they fired tear gas behind them, at which point a fire-fight commenced.[14] Sociologist Natalia Camacho Balderrama recounts that "for one day, the center of the city of La Paz, seat of government, served as a 'battlefield', [with] indiscriminate crossfire".[19] From the roof of the Foreign Ministry, police units shot tear gas and ammunition at the soldiers, who responded in kind. A police officer walking outside the Foreign Ministry building was shot in the leg, while another was shot in the head, dying instantly. The PN's Immediate Action Group (GAI) arrived at GES headquarters soon after, carrying long storage boxes—presumed to be containing sniper rifles—that they brought into the National Institute of Agrarian Reform. Police also occupied the building housing Radio Nueva América, seizing apartments and offices between the sixth and tenth floors, from which they fired on military units below. An infantry captain standing on the roof of the Palacio Quemado was shot dead and a soldier attempting to aid him was also killed.[14]

From inside the palace, Mesa states that "what I saw was hell". He likened the events to the violent riots that culminated in the lynching of President Gualberto Villarroel in 1946. At around 1:30 p.m., Tellería informed President Sánchez de Lozada that the military was no longer confident in its ability to protect him inside the building and requested that he evacuate the palace.[20] In the ensuing days, multiple outlets reported that the president was smuggled out in an ambulance.[12][21] Mesa called that theory "lying nonsense", assuring that Sánchez de Lozada left in the presidential car as part of a caravan of a dozen other vehicles: "You would have to be extremely inept to choose an ambulance having the presidential armored car—the only armored vehicle in the palace that day— ...". The president, vice president, and cabinet spent the rest of the day at Sánchez de Lozada's private residence in Obrajes.[22]

Anarchy in La Paz

At 3:30 p.m., Ombudsman Ana María Romero called Vice President Mesa asking him to relay to the president her request that he withdraw the tax hike to avoid a wider catastrophe across the country. Sánchez de Lozada agreed, and an hour later, in a televised address to the nation, the president announced the suspension of the tax plan and the withdrawal of the bill from Congress.[23] He also ordered the withdrawal of military forces, pleading for the populace to end the violence.[12] By that point, Mesa states it was already realized that "the city, without a government, without a police force, was abandoned to its fate".[22] In the absence of rule of law, La Paz devolved into anarchy, engulfed by a wave of looting, rioting, and vandalism.[24]

Vandals targeted multiple public buildings, with government and municipal institutions bearing the brunt of the damage. A total of seven buildings were set on fire, which, given the absence of firefighters, continued to smolder into the night. Most notable was the Vice Presidency, which caught on fire at around 5 p.m. As the building burned, the vice president's security team worked to safeguard the archives at the Library of Congress from being consumed by the flames. Other buildings that sustained heavy damage included the Ministry of Finance, which was looted and burned, and the El Alto Mayor's Office, which suffered a large assault by rioters. Mobs also targeted the headquarters of the country's main political parties, destroying the offices of Sánchez de Lozada's Revolutionary Nationalist Movement and those of the Revolutionary Left Movement, his main coalition partner. The former—an antique building from the early 20th century—sustained such heavy damage that it collapsed in on itself, leaving only the exterior walls intact.[12][23][25]

Protests and riots in all parts of La Paz and El Alto continued into the afternoon of 13 February. Guards at the Bolivian Customs Service were overpowered, with looters stealing trucks full of imported merchandise. In El Alto, looters stormed the local Coca-Cola plant, breaking down the surrounding brick walls and overwhelming security and company employees attempting to repel them. By this point, the army had been deployed in an attempt to quell the unrest. At the Coca-Cola plant, Air Force troops fired on the looters, killing four and wounding several more.[26] Sometime after noon, Ronald Collanqui, a 28-year-old handyman, was sighted on the roof of a building and was shot from across the street by a police sniper who mistook him for an enemy combatant. At 1:20 p.m., Ana Colque, a 24-year-old student nurse, was shot through the chest while attempting to apply first-aid to Collanqui; both died from their injuries.[24]

In the capital and elsewhere in the country, protests erupted demanding Sánchez de Lozada's resignation. Large demonstrations against the government were carried out in Cochabamba, Oruro, and Santa Cruz de la Sierra.[24] These were supported by the CEPB and the COB, the latter of which publicly declared the president "arrogant" and "incapable" and demanded that he resign, calling for popular demonstrations in all nine departmental capitals. In response, Sánchez de Lozada assured that he had no intentions of stepping down, instead calling for a public conference between the country's leading political parties and social movement organizations.[27]

By the end of the day, the government successfully brokered a deal with the PN that, among other aspects, granted police the payment of government bonds, compensation for the families of dead or injured officers, and the allocation of funds for the procurement of new equipment and uniforms. Save for some holdouts—such as around 2,000 security personnel who rioted in Palmasola prison demanding a 40% pay increase—the agreement returned around 22,000 law enforcement agents to the streets. With the return of police, the riots quickly subsided.[27] Thirty-one people, between civilians, police, and soldiers, died as a result of the unrest, with a further 268 wounded.[18] At the time, it was the worst period of violence since the country's transition to democracy in 1982.[21]

Aftermath

Three days after the riot subsided, in an opinion-piece published by Opinión, columnist Lorgio Orellana stated that "a most serious wound has been inflicted on the legitimacy of the current social regime, from which it will take years to recover, if it is not first swept away by a popular insurrection".[28] The events that came to be known as "Black February" served as a precursor to prolonged public discontent with President Sánchez de Lozada's administration. Within eight months, the president had resigned and fled the country in the face of a resurgent wave of violence.[29]

The IMF was also questioned for its role in pushing for public policies that resulted in mass unrest. Economist Carlos Villegas assured that "in addition to the stubbornness of the government, [responsibility for the violence of February lies on] the IMF, which imposes economic policies". Morales, in turn, deplored the Fund, stating that it "provokes bloodshed [and] confrontation".[30] On 14 February, the IMF issued a public statement saying that it "regretted the tragic events in Bolivia", denying that it bore any responsibility for the violence, and pledging to continue negotiations with the government. By 2005, both sides had still been unable to reach consensus on a long-term lending agreement. In their analysis of events, Jim Shultz and Lily Whitesell wrote that "over and over again, when confronted with realities on the ground that fall short of their theories and predictions, IMF and World Bank officials place the blame not on the theory but on faulty implementation by poor governments. But the options open to poor governments are much more difficult than the IMF is willing or able to admit."[24]

OAS report

One day after the riots were quelled, on 14 February, Foreign Minister Carlos Saavedra Bruno transmitted an urgent request to the Organization of American States (OAS) requesting an impartial investigation into "acts of terrorism that affect the security of the population and the rule of law itself". In response, on the same date, the Permanent Council of the OAS adopted Resolution CP/RES. 838 (1355/03) determining the body's decision:[31][32]

- To express its full and decisive support for the constitutional government of the president of the Republic of Bolivia, Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada, and for the democratic institutions.

- To condemn the use of violence and other undemocratic acts that disrupt democracy and good governance in Bolivia.

- To reaffirm that the constitutional subordination of all state institutions to the legally constituted civilian authority and respect for the rule of law on the part of all institutions and sectors of society are essential elements of democracy.

- To reaffirm the firm resolve of the member states to apply the mechanisms provided in the Inter-American Democratic Charter for preserving democracy.

- To urge all sectors of Bolivian society to strengthen channels of dialogue and tolerance and to refrain from promoting political violence.

- To reiterate that the promotion and observance of economic, social, and cultural rights are inherently linked to integral development, equitable economic growth, and the consolidation of democracy in the states of the Hemisphere.

- To support the efforts of the government of the Republic of Bolivia to reach, with due urgency, agreements with the international financial institutions` that will contribute to democratic, social and financial stability in that country.

OAS Secretary-General César Gaviria met on 6 March with President Sánchez de Lozada. The OAS agreed to collaborate with the Prosecutor's Office in its investigation of events, providing technical cooperation as well as international experts in the field of criminal investigation. In compliance with the Bolivian government's request, the OAS also published a full report describing the events that occurred between 12 and 13 February, outlining the body's conclusions in this regard and making recommendations to prevent the recurrence of similar happenings.[33] The OAS attributed blame for the unrest to the PN, stating that what occurred between 12 and 13 February was an "insubordination by members of the police against the Bolivian Constitution and laws". However, the report also included that, though Sánchez de Lozada's life was endangered, "at the moment, there is not enough evidence to affirm categorically that said shots [that were fired at the Palacio Quemado] responded to a pre-established plan to assassinate the president of the Republic of Bolivia".[34]

Criminal proceedings

A total of nineteen people—nine police officers, six civilians, and four soldiers—were charged for the deaths that occurred. The trial against them was installed in 2008, but various legal challenges have led to the suspension or postponement of over twenty hearings. On 24 August 2021, the Eighth Criminal Sentencing Court in La Paz held a hearing to make way for the commencement of the trial, but as of 7 November 2024, it has not been initiated.[18]

See also

References

- ^ Kehoe, Machicado & Peres-Cajías 2019, p. 16

- ^ Medinaceli, Rubén (20 February 2019). "'Impuestazo' de febrero 2003, el fracaso del neoliberalismo". Página Siete (in Spanish). La Paz. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ a b Shultz & Whitesell 2005, p. 40

- ^ Shultz & Whitesell 2005, pp. 40–41

- ^ a b c Crespo, Luis (10 February 2003). Written at La Paz. "Bolivia: impuesto polémico". BBC Mundo (in Spanish). London. Archived from the original on 17 October 2003. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ a b Camacho Balderrama 2003, p. 1

- ^ a b c Mesa Gisbert 2010, p. 60

- ^ Shultz & Whitesell 2005, p. 41

- ^ a b c Camacho Balderrama 2003, p. 2

- ^ Crespo, Luis (10 February 2003). Written at La Paz. "Bolivia: impuesto polémico". BBC Mundo (in Spanish). London. Archived from the original on 17 October 2003. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

... el diputado y dirigente sindical Evo Morales, dijo que las medidas económicas anunciadas pretenden 'descargar la crisis económica sobre las espaldas del pueblo'.

- ^ Staff writer (10 February 2003). Written at Oruro. "El Presidente dice que sin el 'impuestazo' Bolivia no es viable". Agencia de Noticias Fides (in Spanish). La Paz. Archived from the original on 28 April 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

'Otro tipo de presupuesto no sería posible sin poner en peligro la estabilidad de nuestra economía ... Si no se aprueba un presupuesto como éste, [Bolivia] va ir a un colapso económico'.

- ^ a b c d Gori, Graham (13 February 2003). "14 killed in Bolivian riots". The Guardian. London. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 26 August 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f Shultz & Whitesell 2005, p. 42

- ^ a b c d e f g Organization of American States 2003, Sec. 5(a).

- ^ a b Mesa Gisbert 2010, p. 58

- ^ Camacho Balderrama 2003, p. 3

- ^ Mesa Gisbert 2010, pp. 58–59

- ^ a b c Quispe, Jorge (12 February 2022). "Todo lo que tiene que saber 19 años después de la crisis de 'Febrero negro'". Página Siete (in Spanish). La Paz. Archived from the original on 10 March 2022. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ Camacho Balderrama 2003, p. 5

- ^ Mesa Gisbert 2010, pp. 60–61

- ^ a b Forero, Juan (16 February 2003). "Economic Crisis and Vocal Opposition Test Bolivia's President". The New York Times. Bogotá. Archived from the original on 27 May 2015. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ a b Mesa Gisbert 2010, p. 61

- ^ a b Mesa Gisbert 2010, p. 62

- ^ a b c d Shultz & Whitesell 2005, p. 43

- ^ Camacho Balderrama 2003, p. 4

- ^ Organization of American States 2003, Sec. 5(b).

- ^ a b Staff writer (14 February 2003). Written at La Paz. "Crece la protesta en Bolivia pidiendo la renuncia del presidente". Diario Río Negro (in Spanish). General Roca. Archived from the original on 28 June 2003. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ "Recordando el quiebre de Febrero Negro". Opinión (in Spanish). Cochabamba. 16 February 2017. Archived from the original on 1 May 2022. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

... el columnista Lorgio Orellana afirmaba el 16 de febrero: 'Se ha infligido la herida más grave a la legitimidad del régimen social vigente, de la cual le va a costar años recuperarse, si es que antes no resulta barrido por una insurrección popular'.

- ^ Staff writer (17 October 2003). Written at La Paz. "Bolivian president resigns amid chaos". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 27 August 2013. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ "Otro revés para las recetas del FMI". Diario Río Negro (in Spanish). General Roca. 14 February 2003. Archived from the original on 22 February 2003. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

Evo Morales ... deploró 'cómo el Fondo Monetario Internacional provoca hechos de sangre [y] confrontación ...'. El economista Carlos Villegas opinó que la responsabilidad de la convulsión en Bolivia es 'además de la tozudez del gobierno, del FMI, que impone las políticas económicas'.

- ^ Organization of American States 2003, Sec. 2.

- ^ "CP/RES. 838 (1355/03): Support for the Constitutional Government of the Republic of Bolivia". oas.org. Washington, D.C.: Organization of American States. 14 February 2003. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ Organization of American States 2003, Sec. 3.

- ^ Organization of American States 2003, Sec. 6.

Footnotes

- ^ The Special Security Group was the National Police's riot control unit, charged with responding quickly when riots occur.[14]

- ^ Due to the mountainous topography of La Paz, the Foreign Ministry is located on a higher level than the Palacio Quemado, offering a tactical advantage in an armed conflict.

- ^ According to Mesa, such a meeting was an exceedingly exceptional occurrence as the president typically never called cabinet meetings earlier than 9 p.m.[15]

Bibliography

- Camacho Balderrama, Natalia (2003). La 'rebelión' de febrero: una historia que no se puede reeditar (Report). Cuadernos de desarrollo humano sostenible. CERES: Centro de Estudios de la Realidad Económica y Social. pp. 1–6.

- Kehoe, Timothy J.; Machicado, Carlos Gustavo; Peres-Cajías, José (2019). The Monetary and Fiscal History of Bolivia, 1960–2017 (Report). NBER Working Paper Series. National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/w25523.

- Mesa Gisbert, Carlos D. (2010). Presidencia Sitiada: Memorias de mi Gobierno (in Spanish) (4th ed.). La Paz: Plural Editores and Fundación Comunidad. pp. 58–62. ISBN 978-99954-1-122-0.

- Shultz, Jim; Whitesell, Lily (1 May 2005). "Deadly consequences: how the IMF provoked Bolivia into bloody crisis". Multinational Monitor. Vol. 26, no. 5–6. Gale Academic OneFile. pp. 39–44.

- "Report of the Organization of American States (OAS) on the events of February 2003 in Bolivia". oas.org (in Spanish). Washington, D.C.: Organization of American States. 2003.

External links

- Archival footage depicting the events of Black February. Digitization of VHS tapes archived by the Prosecutor's Office.

- 12 February 2003. Ten years later. Testimony of Carlos Mesa on the events of Black February (in Spanish).