Adam Koc

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Adam Ignacy Koc | |

|---|---|

Koc, sometime before 1937 | |

| Minister of Treasury | |

| In office 30 September 1939 – 9 December 1939 | |

| Prime Minister | Władysław Sikorski |

| Preceded by | Eugeniusz Kwiatkowski |

| Succeeded by | Henryk Strasburger |

| Minister of Industry and Trade | |

| In office 9 October 1939 – 9 December 1939 | |

| Prime Minister | Władysław Sikorski |

| Preceded by | Antoni Roman |

| Succeeded by | Henryk Strasburger |

| Vice-minister of Treasury | |

| In office 23 December 1930 – December 1935 | |

| Vice-minister of Treasury | |

| In office 10 September 1939 – 30 September 1939 | |

| Prime Minister | Felicjan Sławoj Składkowski |

| 2nd Vice-minister of Treasury | |

| In office December 1939 – March 1940[1] | |

| Prime Minister | Władysław Sikorski |

| State commissioner for the Bank of Poland | |

| In office 3 January 1932 – 7 February 1936 | |

| Head of the Bank of Poland[2] | |

| In office 7 February 1936 – 8 May 1936 | |

| Preceded by | Władysław Wróblewski |

| Succeeded by | Władysław Byrka |

| 2nd Convocation member of Sejm | |

| In office 4 March 1928 – 30 August 1930 | |

| Constituency | Nonpartisan Bloc for Cooperation with the Government (BBWR) |

| 3rd Convocation member of Sejm | |

| In office 16 November 1930 – 10 July 1935 | |

| Constituency | Nonpartisan Bloc for Cooperation with the Government (BBWR) |

| 4th Convocation member of Sejm | |

| In office 8 September 1935 – 13 September 1938 | |

| Constituency | Camp of National Unity (OZN, from 1937) |

| 5th Convocation member of Senate | |

| In office 13 November 1938 – 2 October 1939 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Adam Ignacy Koc August 8, 1891 Suwałki, Congress Poland |

| Died | February 3, 1969 (aged 77) New York City |

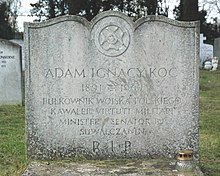

| Resting place | Wolvercote Cemetery, Oxford, England 51°47′29″N 1°16′24″W / 51.79131°N 1.27321°W |

| Political party | Nonpartisan Bloc for Cooperation with the Government (BBWR) |

| Other political affiliations | Camp of National Unity (OZN) |

| Alma mater | Wyższa Szkoła Wojskowa, 1924 |

| Profession | soldier, journalist, politician |

| Awards | Virtuti Militari, Order of Polonia Restituta Officer's Cross, Cross of Valour (Poland), Cross of Independence, Officer's Star "Parasol", Légion d'honneur Officier |

| Signature | |

| Nickname(s) | Witold, Szlachetny, Adam Krajewski, Adam Warmiński, Witold Warmiński |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Polish Legions; Polish Armed Forces |

| Years of service | 1915–1928 (formally until 1930), 1939 |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Battles/wars | World War I, Polish–Soviet War |

Adam Ignacy Koc (31 August 1891 – 3 February 1969)[3] was a Polish politician, MP, soldier, journalist and Freemason. Koc, who had several noms de guerre (Witold, Szlachetny, Adam Krajewski, Adam Warmiński and Witold Warmiński), fought in Polish units in World War I and in the Polish–Soviet War.

In his youth, he was a member of the Revolutionary Association of the Nation's Youth, the Union of Active Struggle and the Riflemen's Association. He then became a commandant of the Polish Military Organisation, first in the Warsaw district, and then its Commandant-in-Chief. Adam Koc was one of the officers of the Polish Legions and a member of so-called Convent of Organisation A.

In the Second Polish Republic, Adam Koc joined the Polish Armed Forces, in December 1919, where he was given command of the 201 Infantry Regiment of Warsaw's Defense, which later became a Volunteer Division (31 July – 3 December 1920). Afterwards, he served in the Ministry of Military Affairs, in different positions. A participant in the May Coup, he was promoted in 1926 to be chief of the Command of VI District of Corps in Lwów, a position he held until 1928.

Considered a member of Piłsudski's colonels group, he was elected to the Sejm three times and once to the Senate. He was also multiple times in office, mostly in financial positions (he was Vice-Minister of Treasury and head of the Bank of Poland). He was one of the negotiators of loans to the Second Polish Republic from the UK and France.

As a Sanational politician, he created the newspaper Gazeta Polska, published from 1929 to 1939. He was editor-in-chief of its Sanational predecessor Głos Prawdy in 1929.[4]

After Piłsudski died in May 1935, Adam Koc joined the people close to Edward Rydz-Śmigły. He became commandant-in-chief of the Association of Polish Legionists.

In 1936–1937, Koc started co-creating a new political entity, the Camp of National Unity (OZN). He became its head a year later. He was supportive of the idea of OZN's approach towards the radical right National Radical Camp Falanga and right-wing National Democracy.

As World War II started, Koc coordinated the evacuation of the Bank of Poland's gold reserves. He served as Minister of Finance, Trade and Industry for a short period in 1939, before he fled to the United States in 1940. He became one of the active members of the Józef Piłsudski Institute of America and died, still in exile, in 1969.

Early life

[edit]Adam Koc was born into an aristocratic family from Podlachia. It is possible that the family derived itself from the area near Biała Podlaska.[1]

His grandfather, Leon, was a veteran of the January uprising and mayor of Filipów and Sereje, both near Suwałki, Koc's hometown, while his grandmother, Waleria, was part of the Polish National Government. Adam's father, Włodzimierz (1848–1925) was a teacher of ancient languages. His marriage with Helena (née Pisanko) brought three children: Stefan (1889–1908), Adam Ignacy himself and Leon Wacław, the youngest of them (1892–1954).[5][6]

After the death of Adam's mother in 1894, his aunt, Elżbieta Pisanko, took care of them. Five years later, the family moved to a rented flat in Suwałki. He started school in 1900 and he attended the Russian Boys' Gymnasium in Suwałki. It is there, most probably,[5] that Koc became involved in the pro-independence activities, participating in self-taught additional lectures, in 1901.[7]

During the 1905 revolution he was part of the strike action gymnasium committee. As a result, he and future politician and MP Aleksander Putra were expelled from the school.[8] At the time, he was a member of the National Workers' Union, an organisation with close ties with the National Democracy. He continued his education in January 1906 in the newly opened Polish Private Seven-class Trade School in Suwałki (now School Union nr. 4).[9] Later on, his father sent Adam to Kraków, where he attended the Philosophical College of the Jagiellonian University. In order to do so, he had to pass final exams in one of the Kraków's gymnasiums. He did so on 20 June 1912, in then named IV classical gymnasium (now IV Tadeusz Kościuszko Lyceum), located in Podgórze (then a separate city), on quite a low level (mostly, he received a "satisfactory" grade, with only Greek and Latin passed on a "good" one), which was enough, however, to start Polish studies there.[5]

Pro-independence activity (1909–1914)

[edit]Before World War I

[edit]

Koc had been in Kraków for three years when he wrote his Matura exam in 1912. At the time he committed to pro-independence conspiracy organisations,[1] and was listed among the radical youth. Władysław Studnicki was his mentor, while Aleksander Putra, Bolesław Kunc and Bolesław Dąbrowski were his closest cooperators. In the fall of 1909, Koc joined the newly created Revolutionary Association of Nation's Youth (ZRMN),[10] which was introduced into the conspirative Union of Active Struggle (ZWC) by Studnicki,[10] despite fears that the organisation bore a socialist character. There, Koc received his first pseudonym, Witold. His brother, Leon, joined the organisation in 1911, after Adam introduced him.[5]

Koc was engaged in the Riflemen's Association, a legal organisation related to ZWC. Initially he was responsible for the financial state of the Kraków branch,[7] but Koc was sent to Grodno in late May 1910 by Kazimierz Sosnkowski and Józef Piłsudski (where his retired father lived), so as to make a detailed description of the fortress.[1] The task was done well, while the maps and sketches were sent via Aleksander Prystor. It is probable that it was the reason Koc could complete the officer's course, organized by the Union of Active Struggle in Stróża near Limanowa, in Austrian Galicia, in 1912, and therefore promoted to a higher rank in the ZWC a year later. In spring 1914, he passed an exam that gave him an officer's rank in the ZWC and an Officer's Star "Parasol" award.[11] Simultaneously, Koc was an adjutant of the main headquarters of Riflemen's Organisation for the Russian partition affairs, starting from October 1913.[5]

Polish Military Organisation (1914–1919)

[edit]On 10 August 1914, Koc came to Warsaw from Druskininkai on the order of Walery Sławek, to take command of the local branch of the Union of Active Struggle in the Russian partition.[12] Soon afterwards, the Union of Active Struggle and the Riflemen's Association in Congress Poland united under leadership of Karol Rybasiewicz, formerly commandant of the Polish Rifle Squads. Koc became his deputy, and in August 1914, the new body was named the Polish Military Organisation (POW), led by Piłsudski's emissary, Tadeusz Żuliński.[13] The main target of the new organisation was to create sabotage actions behind the Russian army. Koc was one of the members of the Chief Commandment of POW. In addition, Koc commanded the Warsaw district of the organisation from the beginning of 1915. In February 1915 he was advanced to Podporuchik by Żuliński.[14]

Koc desperately wanted to fight Russians on the front, among Piłsudski's Legions, an occasion that could have been possible unless the front stabilized by spring 1915. Then, Żuliński sent him to Piłsudski (then actively in fight) with reports on POW's activity. Normally, such a person could cross the frontline to the 1st Brigade of Polish Legions, but it proved to be impossible. To fulfill the task, Koc had to use the northern route, via Finland and Sweden. Alias Adam Krajewski, Koc left Warsaw on 25 May 1915,[5] giving up his POW's position.[11]

He arrived in Petrograd, and started to move towards Helsinki, illegally crossing the border between Russia and the Great Duchy of Finland.[1] Then, Koc was transported to Stockholm, in agreement with Finnish pro-independence organisations.[12] There, he met another messenger from POW, Aleksander Sulkiewicz. Problems with getting an Austro-Hungary visa, both had to wait for them in Kopenhagen. Having received the documents, Koc arrived in Piotrków Trybunalski (then occupied by the Triple Alliance militia), where he met with Adam Skwarczyński. He then finally reached Annopol, then Piłsudski's headquarters.[12] The reports were given, and, on Koc's will, he was allowed to participate in the Legions.[5]

Polish Legions (1915–1918)

[edit]Having completed the task given by Żuliński, he joined the 5th Infantry Regiment, which was part of the 1st Brigade of the Polish Legions.[1] It almost coincided with the Central Powers countries' occupation of Lublin in summer 1915.[15]

He received a task coinciding with his earlier life experience: supporting the newly summoned Lublin's National Department – an organisation aiming at the propagation of Piłsudski's policies (to counteract the Commandment of Legions, controlled by Central Powers). By doing so, he raised suspicions among the Austro-Hungarian militia, so he was sent to the front line. Koc struggled with pneumonia and malaria, which was aggravated by his sight issues. Koc commented on his state:

While executing my duties, I had some problems, because my sight was weak. I saw nothing at night, whilst the attacks sometimes took place, when we were sent to patrol the areas near the front line. Which was why it was needed to find a deputy soldier who could substitute the weakened sight, while conducting in the dark

— Koc, Adam, "Wspomnienia" [Memories]. Wrocław: Towarzystwo Przyjaciół "Ossolineum", 2005.

On 18 September 1916, Koc was severely wounded in the Battle of Sitowicze, in Volhynia. He was shot near his liver, while on a spy mission. Sulkiewicz was shot dead. Felicjan Sławoj Składkowski cared for him at the battlefield. The wounded Koc was transported to the Legions' clinic in Lublin, and then to Kraków.[5]

He finished his treatment at the clinic on 31 January 1917. Koc returned to political life in the Legions, where he became one of the founders of the so-called Analphabet Association – a conspirative military organization in the 5th Infantry Regiment supporting Piłsudski's pro-independence policy.[16] By that time he was one of the piłsudczyk (a supportwe of Piłsudski) who has already been a decent authority in the Legions.[17]

His actions did not remain unnoticed by the Austro-German generals, so Koc was sent to Ostrów Mazowiecka for additional schooling, as a punishment. Additional trouble came to Koc after the oath crisis (9-11 July 1917), when, as one of the officers of the Legions, he was imprisoned at the camp in Beniaminów, while his brother Leon was imprisoned at Szczypiorno (now part of Kalisz).[18] At Beniaminów, Koc worked to convince other prisoners to join Piłsudski and to continue resistance. Koc was released on 22 April 1918, with his health deteriorating.[19]

Polish Military Organisation (1918)

[edit]

After he was freed from the prisoner-of-war camp, Koc rejoined the Polish Military Organisation. Jan Zdanowicz-Opieliński, who was then the Main Commandant of POW district number 1 (the one that ruled over the German-occupied territory from its headquarters in Warsaw), convinced the then head of POW, Edward Rydz-Śmigły, to transfer his command to Koc.[5]

As POW's Main Commandant, Koc reorganized his Command, and created fast-moving squads for sabotage actions, on the order of Edward Rydz-Śmigły. He initiated protests against the German police and coordinated POW activity with the Armed Squads of the Polish Socialist Party. His successes increased his authority in the military organisations.[5] While Main Commandant, he made close ties with Bogusław Miedziński (who was responsible for correspondence with the political constituencies, mostly Polish political parties[20]) and Rydz-Śmigły. The latter soon gave over his functions to Koc, in September 1918.[21]

At the same time, Koc substituted for Tadeusz Kasprzycki in the Convent of Organisation A, which was created in summer 1917, as a conspiratorial group of Piłsudski supporters.[5]

As the process of the so-called Lublin government advanced (early November 1918), German-led military councils were organized in Warsaw. Koc initiated the demilitarisation of some part of them.[5]

On 10 November 1918, together with Prince Zdzislaw Lubomirski, part of the Regency Council of the Kingdom of Poland, he welcomed Józef Piłsudski and one of his fellow warriors, Kazimierz Sosnkowski, who returned by train to Warsaw from internment in Magdeburg.[1][12] Then, Koc ordered his subordinates to disarm German soldiers in Warsaw.[22] This done, Józef Piłsudski and the Provisional People's Government of the Republic of Poland could then peacefully enter Warsaw to start governing the newly created Polish Republic.[5]

Polish Army (1918–1930)

[edit]

Independence (1918–1920)

[edit]Even though Koc was busy as Main Commandant, he served as a referent for the I Department (Organisational) of the Polish Armed Forces on the affairs of POW incorporation, until mid-December 1918.[6] The POW division was then merged with the VI Section (Informational) of the General Staff with Koc at its head.[23] On 11 May 1919, its name changed to the Second Department of Polish General Staff. At first, he served in the Intelligence Bureau of the Second Department. He was afterwards directed to the Wojenna Szkoła Sztabu Generalnego (Military School of the General Staff) for additional schooling, from 13 June to 1 December 1919.[5]

Later, on 17 January 1920, by decree of the Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Armed Forces, Józef Piłsudski, Koc was officially accepted in the Polish Armed Forces as a captain[24] (he had been informally advanced to the rank on 17 December 1918[25]). On the same date, another decree (dated 1 January 1920) was published he was awarded the Silver Cross of Virtuti Militari.[26] By that time, he had been nominated as head of the VI Section (of Propaganda and Soldiers' Care).[27] Nevertheless, he continued his duties as POW Main Commandant. It is unclear, however, which of his actions there were part of his official duties.

As Koc received the most prestigious military award in Poland, he became secretary of the Temporary Council of the Virtuti Militari Award[28] (as one of the 11 first recipients of the award since its restoration in August 1919,[29] on 21 January 1920[12]). He was as well part of the Statute Commission.[28] He had to leave shortly, however, since he was to go to Ukraine in May until June 1920 to aid Symon Petlura in communication issues and, later on, the POW soldiers who remained alive.[30]

War with Union of Soviet Socialists' Republic (1920)

[edit]On 11 June 1920, on the order of the Ministry of Military Affairs, Koc was promoted to lieutenant colonel, together with other Polish Legion officers.[31] Soon he was given command of the 201st Infantry Regiment (18 July 1920), which consisted mainly of POW soldiers. The regiment was subordinated to Władysław Sikorski's, and then, as the regiment was incorporated into the 22nd Infantry Division, over it as well. All of the militia were created as part of the Volunteer Army, which itself was a result of mobilisation to the Polish Armed Forces.[32]

At first, in late July, Koc and his regiment were stationed in Suraż near Białystok. The regiment began fighting against Soviet forces. As the regiment was incorporated into the Volunteer Division, Koc continued fighting on the Northern Front. The successes of his army started only after the turning point of the conflict. For example, on 15/16 August 1920, his soldiers took over Nasielsk,[33] after Sikorski's counterattack a day earlier. Koc was unable to fully destroy the 3rd Cavalry Corps, led by Hayk Bzhishkyan, as the Soviet cavalry escaped encirclement.[33]

Soon after, Koc's Division was incorporated into the 3rd Army of Edward Rydz-Śmigły, where Koc participated in the successful attack on Grodno. Part of the 22nd Division took part in Żeligowski's mutiny,[5] while the rest (Koc included) fought until 3 December 1920, when his division was dissolved.

Peace (1921–1925)

[edit]As the Polish–Soviet conflict waned, Koc came to Warsaw, where he took a course of informational lectures for higher rank officers, starting from 20 January 1921.[5]

Service in the III Department

[edit]As the war officially finished, Piłsudski gave Koc command of the newly summoned III Department of the General Staff for the Preparation of Reserves affairs. His task was to support organizations that were to prepare the population for possible military conflict. The department controlled military education of Polish youth and the reserves.[34]

Koc participated in the International Riflemen's Organisation councils on the behalf of Ministry of Military Affairs.[35] He was an advocate for the democratisation of relationships inside the military and for stronger ties between the people and the army,[36] which won him esteem among his subordinates. Simultaneously, he was regularly published in the Strzelec, Rząd I Wojsko and Bellona military magazines. These facts resulted in a positive opinion of Koc's work by his boss in the III Department, Colonel Marian Kukiel, but in the highest military circles, namely, of Stanisław Szeptycki, then Minister of Military Affairs.[5] On 3 May 1922, Koc was given an advantage in placement.[37] He was placed in 135th place of senior infantry soldiers.[38]

While serving in the III Department, Koc was part of a conspiracy organisation called "Honor i Ojczyzna" (1921–23), which was to train new soldiers, maintain morale and depoliticise the army's structure.[39][40] Together with Kazimierz Młodzianowski, Koc, as the representative of the Polish Military Organisation and the Legions, was part of the chapter.[41] The organisation was created by Władysław Sikorski, himself a right-of-center politician, nevertheless, Koc received consent from Józef Piłsudski and Kazimierz Sosnkowski, both on the left.

At the time, Koc was writing poetry (alias Adam Warmiński). His book of poetry and prose was published in 1921.[42]

First attempt of Socialist takeover

[edit]

In mid-December 1922, as Gabriel Narutowicz was assassinated, Koc took part in the Piłsudski's officers meeting in the II Department's headquarters. The meeting aimed at calming the created situation by Piłsudski's military intervention (albeit Piłsudski had no formal power to do so) and, eventually, at taking over power in Poland.[43] The officers present (including Koc, Bogusław Miedziński, Ignacy Matuszewski, Ignacy Borner, Konrad Libicki, Kazimierz Stamirowski and Henryk Floyar-Rajchman) contacted the headquarters of the Polish Socialist Party (PPS) in order to organise a general strike, a plan that did not come to life because Ignacy Daszyński refused to cooperate.[44]

Pre-May Coup activity

[edit]From 2 November 1923, Koc attended another schooling course in the Wyższa Szkoła Wojenna.[45] Having completed his military studies, he was accepted as the I referent in the II Army Inspectorate in Warsaw (under Łucjan Żeligowski). Even though he worked at the Army Inspectorate, in addition, he was made head of 5th Legions' Infantry Regiment.

On 1 December 1924, Koc was promoted to colonel, his highest military rank, with 17th place on the list of seniority among Polish infantry.[45] Two months later, colonel Koc was nominated as a deputy of the commandant of the Center of Practical Army Schooling in Rembertów (then a separate town).[46]

Koc became a freemason before 1921 demitted on 23 March 1928.[47] In 1925–1926, while serving in Rembertów, Koc was part of the National Grand Lodge of Poland,[48] on Piłsudski's recommendation.[49][50]

Koc-group

[edit]From mid-1924 until winter of 1925, meetings took place in Koc's apartment and in the Mała Ziemiańska cafe on Mazowiecka street in Warsaw. The participators from the piłsudczycy circles (including Józef Beck, Ignacy Matuszewski, Bogusław Miedziński, Kazimierz Stamirowski, Kazimierz Świtalski, Henryk Floyar-Rajchman and the Starzyńscy brothers Roman and Stefan) supported a coup d'état, so the meetings were mostly about preparing for the event. Preparations were interrupted, however, by Piłsudski, in December 1925.[51] Despite their suspension, they had some impact on the future May 1926 events.

May Coup and beyond (1926–1930)

[edit]May Coup

[edit]On 11 April 1926, Koc began serving as head of the Department for Non-Catholic Religions in the Ministry of Military Affairs. The position had taken him to Warsaw for the month preceding the coup, time Koc used to help Piłsudski organize it.[5] His role was to inform some of the piłsudskiite officers about the upcoming power takeover just before the event. He fulfilled his mission on 11/12 May, he, Anatol Minkowski, Feliks Kwiatek (both lieutenant colonels) and Karol Lilienfeld-Krzewski (major), visited Kazimierz Sawicki, commandant of the 36th Infantry Regiment and contacted Tadeusz Piskor, commandant of the 28th Infantry Division, to signal Piłsudski's readiness for action. While the coup was in process, Koc was most probably negotiating the strike action announcement on the Polish rail service.[52] He could not, however, know about Stanisław Wojciechowski's location, a fact that upset Piłsudski.[51]

After the May coup, he was nominated as Head of Staff of the Commandment of VI Military District in Lwów, on 14 September 1926 (the office he held until 4 March 1928).[53][54] The purpose of his nomination is subject to controversy. According to Marian Romeyko, he was to "supervise" his boss, Władysław Sikorski,[55] a version rejected by Bogusław Miedziński, who claimed Koc, along with other officers from the so-called Koc-group, were eliminated from Warsaw, even though Marszałek did not explain why and how that happened.[44] It might be possible that Piłsudski was disappointed in Koc after his request to locate Wojciechowski during the coup. Another version was that Piłsudski was afraid of a financial scandal, caused by Jan Lechoń's behaviour. The editor of Cyrulik Warszawski (Koc was an initiator and an organiser of the comical journal)[56] was using Koc's generosity to support the magazine, which might cast a shadow over the new political system, on the grounds that budget money was used for political purposes.[5]

After serving in Lwów for 1,5 years, he became Commandant of Infantry Officers Staff. By then, Koc decided to enter the political scene. In effect, Koc retired from military service while serving as an MP.[57] He fully retired from military affairs on 30 April 1930.[58]

Political career (1927–1938)

[edit]Initial activity

[edit]Koc's political career started in 1927 when he took part in the Cabinet of the Head of the Council of Ministers. There, decisions upon Sanation policies were made.[59] He entered the Lwów Regional Voivodership Committee, one of several structures that coordinated the electoral campaign of Piłsudskiite party.

In the 2nd Sejm convocation, in December 1928, Koc was invited to the Main Awarding Commission of the Cross of Independence (commemorating the 10th anniversary of Polish independence), becoming one of its first recipients.[60]

MP and journalist

[edit]In the March 1928 parliamentary elections, Koc was elected to the Sejm from the all-state list from the Nonpartisan Bloc for Cooperation with the Government (BBWR) constituency.[6]

Koc is claimed to be one of Piłsudski's colonels, which implies that he was one of the closest MPs to Piłsudski and that he was among the ruling class of the BBWR and Poland. Some authors question this statement: Andrzej Chojnowski writes that "Koc and Miedziński were somewhat removed (from the main positions) by Piłsudski",[61] while historian Antoni Czubiński claimed that Koc never belonged to that group.[62]

As an MP from the Nonpartisan Bloc for Cooperation with the government, he was an informal head of a group of BBWR deputies (from both houses of parliament) from the so-called Eastern Małopolska (i.e. territories of Lwów, Stanisławów and Tarnopol voivoderships) from 1928 to 1929, and again from 1930 on. At the same time, he was Director of Propaganda Section of BBWR, which, on 30 October 1929, helped him create a new pro-sanation newspaper – Gazeta Polska, where he briefly served as editor-in-chief.[63] merging Epoka into Głos Prawdy newspapers (Koc directed the latter from January 1929).[4] The main reason Koc was nominated for the newspaper edition was to get rid of Wojciech Stpiczyński's radical leftist views,[4] which were not favourable for Walery Sławek, part of Piłsudski's colonels and head of BBWR. BBWR was trying to find support in the conservative parties,[64] partly to fight the opposition's Centrolew influences, and partly to make a future coalition with the right-wing parties (mainly National Democracy), which was necessary to retain majority in parliament and government.

Even though he was an MP and formally ceased executing his military duties, he was still active in the military organizations where he had been participating for a long time. He was nominated as vice-director of the Riflemen's Association's Council. Koc became head of the Peowiak Association, uniting the veterans of POW, in March 1928.[65]

Vice-minister of Treasury (1930–1935)

[edit]On 23 December 1930, Mościcki nominated the colonel for Vice-Minister of Treasury.[66] At the time the first finance minister was Ignacy Matuszewski, later succeeded by Jan Piłsudski and Władysław Zawadzki. Koc controlled the organisation of stock exchanges and banks (both the central Bank of Poland and private financial institutions), debt and foreign financial relations, during the Great Depression. According to Janusz Mierzwa, Koc's biographer, he had been summoned to such a position despite his lack of experience, thanks to his humble and honest character. Piłsudski could not have trusted other people, as rumours of bribery in the Bank of Poland came to him.[5] Another factor that might have aided his nomination was Matuszewski's fear of the statist ambitions of Stefan Starzyński.[1] Additionally, Koc was passionate about economic issues.[67] At first, Koc was seen to espouse moderately liberal views on the economy,[68] but he evolved as an advocate of mainly interventionist or even statist actions.[5]

At the beginning of 1932, Koc became State Commissioner for the Bank of Poland.[69] He served for 4 years.

French and British railroad loans

[edit]

As Koc was responsible for international financial relations with his foreign counterparts, Koc actively engaged in discussions over a loan from France for finishing the so-called coal trunk-line - a strategically important communication railroad that was to connect Polish Upper Silesian Industrial Region's coal mines with Gdynia, a fast-developing seaport.

In mid-February 1931, Koc arrived to Paris to discuss the financial aspects of the loan, on behalf of the Ministry of Communication.[70] According to the decision signed in France (which was to be valid until 31 December 1975), the French–Polish Rail Association was given rights to the parts of the line under construction (Herby Nowe – Inowrocław and Nowa Wieś Wielka-Gdynia), as well as to exploit the infrastructure on the Częstochowa-Siemkowice section (close to the line). The treaty was the first case when a part of railway line was given for use to a foreign private enterprise, a step lauded by the government (by e.g. showing the importance of Polish loans for Polish-French relations), but equally criticised by the opposition.[71][72] Koc served as vice-director of the rail association for more than three years.

Koc vainly attempted to negotiate another loan from French officials – this time to electrify the Warsaw Rail Knot. He succeeded, however, while continuing talks with British partners. On 8 July 1933, a treaty between English Electric and Metropolitan-Vickers Electrical Co. Ltd., on one side, and the Ministry of Treasury, on another, was signed providing a £1.98 million loan (then approx. 60 mln zł).[1]

The conditions of the loan were much more favorable than the French terms: the project had to be finished in 3–4 years, using materials made in Poland and building additional electrotechnical facilities as well as a power plant near Warsaw, using British capital.[73] The agreement was signed on 2 August 1933,[74] the fact Koc was very content:

The electrification of the Warsaw rail knot will not only have its communicational importance but as well it will positively influence the state of our industry and our working force. I am very content with my visit to London. It gave me the possibility to create new contacts and get to know a lot of influential people from the (British) industry and financial sectors in person. I reckon that these contacts which will be supported by both entities, will increase the mutual self-understanding and will allow achieving the further development of economic cooperation (...)

— Adam Koc, "Wywiad u wiceministra Adama Koca" [Interview with vice-minister Adam Koc], Gazeta Polska, p. 1, from 3 August 1933

Another railroad modernisation loan was signed on 24 April 1934 – this time, with the Westinghouse Brake and Saxiby Co. Ltd., to install air brakes on Polish freight trains. The quote of the loan was the same £1.98 million.[75][76]

International economic conference in London (1933)

[edit]Koc worked to get Poland out of the Great Depression. In June and July 1933, Koc was head of the Polish delegation to the international economic conference in London. Koc presented his views on combating the Depression. He claimed that the main target was to stabilise the currencies via trade liberalisation and customs decrease or abolition.[77] Koc favored the gold standard, signing a "gold countries" declaration with France, Italy, Switzerland, the Netherlands and Belgium, on July 3. The declaration stated, "the will of retaining the free gold standard according to the today's parity [of currencies towards gold] in their own countries, as [written] in the existent monetary laws".[78]

1935

[edit]

1935 was a turning point for Poland. On 12 May 1935, Piłsudski died. To commemorate his death, Koc entered the Main Committee of Józef Piłsudski Commemoration.[59] The place of the General Inspector of the Armed Forces (GISZ) became vacant (no longer occupied by Piłsudski), several candidates were proposed. Koc preferred Kazimierz Sosnkowski, but Mościcki chose Edward Śmigły-Rydz, a person who he thought was absent-minded, especially when compared to Sosnkowski.[79] After the nomination Koc united with Walery Sławek, expecting him to take up power in the havoc caused by Piłsudski's death. Sławek, however, was unable to convince Mościcki to step down, despite evidence that Piłsudski had informally nominated him as his successor,[80] and eventually Sławek was ostracized from the Polish political scene.[81] This deepened the decomposition of the piłsudskiite parties. Koc had to change his orientation, accepting the increasing importance of Edward Rydz-Śmigły. With Bogusław Miedziński and Wojciech Stpiczyński, he co-created the so-called GISZ group, attempting to counterbalance the increasing influence of another informal group – grupa zamkowa (the castle group, named after the residence of Mościcki – the Royal Castle in Warsaw[82]), headed by Mościcki and his protégé – Eugeniusz Kwiatkowski.[5] At the same time, he and Ignacy Matuszewski were considered as the rightmost politicians from the Piłsudski's colonels group.[1]

Legislative elections were due in September 1935. This was a smaller problem, as Koc was reelected for the second time, with an overwhelming 67,408 votes.[83]

In mid-September 1935, he went to one of his last foreign trips as Vice-Minister in the US. His purpose was to gain a missionary loan (i.e. a loan from another country to introduce more money mass into the economy). Arriving in the US, Koc met with Polonia representatives and with Franklin Delano Roosevelt.[84] Later, Koc visited the New York Stock Exchange and some representatives from economic circles. Despite that, the main goal of the visit was not achieved.[5]

When Koc returned to Poland, Walery Sławek's government was dissolved by Mościcki[85] on 12 October 1935. The next day, Eugeniusz Kwiatkowski was nominated as Minister of Treasury and deputy PM.[86] Kwiatkowski was known as an autarkist, while Koc belonged to the classical school, and the two could not coexist. Mościcki declined Śmigły's proposal to install Koc as Prime Minister.[1] Koc resigned in December. with a warm farewell from Kwiatkowski.[87]

Bank of Poland (1936)

[edit]On 7 February 1936, Mościcki nominated Koc as Head of the Bank of Poland.[88] After his nomination, Koc traveled abroad, managing Poland's international loan issues. In France, he met his French counterpart, Jean Tannery, as well as the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Pierre-Étienne Flandin and the Minister of Finances, Marcel Régnier. He also traveled to Great Britain to meet Montagu Norman, then Governor of the Bank of England.[5]

Koc advocated support for profitable enterprises and close cooperation between the Bank of Poland and private financial institutions. As in 1933, Koc protected the gold standard and tried to protect the immense Polish gold reserves. While Koc was in office, the Bank of Poland was not supportive of stock and currency manipulations.[89] The policy, however, could not solve the problem of a sudden drop in foreign exchange reserves at the end of March 1936.

Mościcki summoned a meeting of various officials (including Prime Minister Zyndram-Kościałkowski, Rydz-Śmigły, Tadeusz Kasprzycki, Władysław Raczkiewicz, Roman Górecki, Juliusz Ulrych and Juliusz Poniatowski). Koc proposed a presidential decree to devalue the national currency, but this was rejected by Mościcki. The Head of the Bank of Poland was definitely against such solution, leading Koc to resign on 8 May.[90] Before leaving, Koc convinced Mościcki to transfer 20 mln zł ($3.77M) from the Bank of Poland for combating unemployment by hiring people to work on road construction.[91]

The nomination of Koc as head of the Bank of Poland, while Kwiatkowski, his boss, was in office, is subject to controversy. Mierzwa claimed that neither Kwiatkowski nor Mościcki had a better choice,[1] which implies that the politicians from the "castle group" were searching for a better one, so Koc gave them some time.

Koc joined Bank Handlowy in 1938, becoming its vice-director on 30 March 1939,[92][93] while continuing his government service. Until 1939, Koc served only as a legislator.[1]

Camp of National Unity (OZN) activity (1936–1938)

[edit]Prehistory

[edit]

With the death of Piłsudski, most right-wing politicians gathered around Edward Śmigły-Rydz. Walery Sławek lost support. On 30 October 1935, Walery Sławek dissolved the Nonpartisan Bloc for Cooperation with the Government.[94] Śmigły-Rydz and his partners started working upon its replacement. Śmigły-Rydz was trying to assure control over a Legionist organization – The Association of Polish Legionists (ZLP). On 24 May 1936, Koc took Sławek's position.[95] The same day, Śmigły-Rydz made a speech highlighting the need to protect Poland and to develop its military forces.[96]

By that time, Koc was known as one of Śmigły-Rydz' closest cooperators, which was why the future Marshal chose him to supervise the creation of a new political entity. Miedziński took up that task in December 1936.[5]

Miedziński supported cooperation with right-wing parties. At the beginning of 1937, Miedziński wrote an article in Gazeta Polska, which was essentially a declaration by the Śmigły-Rydz camp that it would create a new political entity. In the same article, Miedziński advocated cooperating with the right (mentioning National Democracy).[97] Simultaneously, Miedziński and Koc were making pertractations with the young nationalist party – National Radical Camp Falanga (ONR "Falanga").[97][98] While talks were in progress, Miedziński drafted the party's declaration, which was accepted by neither Śmigły-Rydz nor Koc. Miedziński mentioned little about agricultural reform, which was one of the reasons why talks with agricultural parties Maciej Rataj and Jan Dąbski failed, apart from lack of consensus on the subject of Wincenty Witos's return and on a new electoral system.[97]

Śmigły-Rydz decided to create his own draft. The draft paralyzed the already uneasy talks with the agricultural parties because it did not consider agricultural reform. Miedziński warned that he was about to quit the Sanation camp if nothing changed.[44]

To achieve consensus, in January 1937, Koc, Miedziński and Śmigły-Rydz met in Zakopane to provide corrections to the Marshal's project. After two days of discussions, Koc received a final draft, which contained some vague points on agricultural reform.[97]

Creation

[edit]On 21 February 1937,[99] Koc made a radio broadcast to declare a new political entity.[100] The party affirmed the 1935 constitution's statement of the primary role of the state and civil solidarity. The declaration featured the need for military protection of the state (including militia heading the country) and maintaining distance from communism. An important part of this statement was the appeal to support Śmigły-Rydz. The program included passages about the importance of the Roman Catholic church. The declaration advocated tolerance towards ethnic minorities, excepting Jews.

The Camp of National Unity (OZN) was attacked as right-wing and antisemitic.[101] Some National Democracy representatives argued that OZN had committed ideological plagiarism.[97] Criticism came from opposition newspapers (e.g. right-wing Kurier Poznański)[102] and some left-wing pro-piłsudskiite representatives.[59] On the other hand, government newspapers such as Gazeta Polska praised the declaration and accented the enthusiasm of other political organisations.[103]

Head of OZN

[edit]

The creation of a new political entity (colloquially called "OZON", Polish for ozone) interested the government itself, leading Koc to visit the president three days after his declaration.

On 22 June 1937, a youth organization of OZN, Union of Young Poland (ZMP), was created. Formally, Adam Koc became director of it, but it was de facto controlled by Jerzy Rutkowski, his deputy. Eventually, on 28 October, Rutkowski took command.[104] Rutkowski was from the radical-right political scene (ONR), but Koc denied any ties between him and ONR "Falanga".[104] The step was a product of cooperation between Koc and ONR's leader, Bolesław Piasecki. It was widely condemned in Legionist and POW circles, for example, on the XIV General Congress of ZLP in Kraków.[5] As criticism grew, OZN ended cooperation with the Union of Young Poland on 22 April 1938.[105] Koc had already stepped down from as leader in favour of Stanisław Skwarczyński. The impulse to do so was Rutkowski's declaration to create an independent organisation and his resignation from OZN.[106]

Assassination attempt

[edit]On 18 July 1937 at 10.15 p.m.,[107] an assassin attempted to execute Koc[107][108][109] while Koc was sitting in his small house in Świdry Małe (now in Józefów near Warsaw). The assassin was instead killed by his own bomb, as it exploded earlier than expected.

The results of the subsequent investigation revealed that the culprit was Wojciech Bieganek from Różopole near Krotoszyn, together with his co-conspirator and brother, Jan, who was arrested the day following the failed attempt.[110] Some pro-Sanation publications suggested that Bieganek was part of a conspiracy among politicians opposing him.[111]

Plan for a coup d'état

[edit]According to some reports, the assassination attempt, as well as OZN's decreasing popularity, were a signal for both OZN and ONR "Falanga" to attempt a second military coup, on 25/26 October 1937 (days when Śmigły-Rydz was to be in Romania).[112] The reports claim that Koc was planning some kind of "St. Bartholomew's massacre" or "Night of the Long Knives", allegedly, with Śmigły-Rydz's support, which was supposed to physically eliminate the Sanational politicians opposing OZN.[112] The plan was to assassinate 300-1500 people[105] and to imprison an equal number, including: Mościcki; Sławek; Kwiatkowski; Janina Prystorowa, wife of then Marshal of Senate, Aleksander Prystor; and Aleksandra Piłsudska, widow of Józef Piłsudski,[112] with Jerzy Paciorkowski and Zygmunt Wenda leading the massacre.

Supporters of the idea claim that a prelude to the action was Śmigły-Rydz's official proposal to change the government to install Witold Grabowski as PM (remembered for his hardline policies), an idea condemned by Stanisław Car, an influential Marshal of Sejm.[105] Moreover, rumours were circulating: right-of-centre Front Morges (Ignacy Jan Paderewski as leader), the delegalised Communist Party of Poland, leftist Sanation faction and the so-called "castle group".[105]

Historians opposed to the notion object that no concrete evidence documenting the plan exists.[112] Moreover, Koc, one of the ostensible organizers, was nominated as Vice-Minister of Treasury by Mościcki, one of the proposed victims. In addition, Władysław Sikorski, a person alienated from Sanation, called Koc for cooperation as Minister of Treasury, Minister of Industry and Trade and, later on, Vice-Minister of Treasury.[5] According to them, the rumours may be classified as "a successful political provocation", addressed to Śmigły-Rydz.[105]

One of the main consequences of the coup was Koc's declaration that he had nothing in common with ONR "Falanga".[104][105]

Resignation

[edit]Rydz-Śmigły claimed that Koc was unfit for ruling OZN. Koc was not a public person, unlike, say, Eugeniusz Kwiatkowski. This fact made it difficult for Koc to lead. Furthermore, Koc was "tired of quarrels with Kwiatkowski, his health was failing", and "he took up the party's position [treating it] as an order from his boss".[1] Also, Koc was neglecting or underestimating the importance of the opposition.[98] To aggravate matters, OZN under Koc was widely seen as approaching fascism (mainly because of Piasecki's influence, despite claiming that "OZN and Falanga had nothing in common"[104]), contrary to Sławek's perfectionism and over-democratization.[113] Finally, on 10 January 1938, Koc resigned from his position as head of OZN, formally because of poor health.[114] Despite the official version, historians claim that Koc was forced to resign by Śmigły-Rydz, in favour of Stanisław Skwarczyński.[97]

On 25 June 1938, Koc's position as Commandant-in-Chief of the Association of Polish Legionists (ZLP) was terminated (although Koc had de facto quit ruling the organization by January 1938[115]). In this way, Koc became an ordinary MP.

Before World War II (1938–1939)

[edit]In Polish parliamentary elections in November 1938, Koc was elected to the Senate. He served on the Statute Commission of the Senate. Additionally, Koc was head of the chamber's Military Commission.[6]

Koc was an employee of Bank Handlowy in 1938–1939, where he became vice-director on 30 March 1939.[116]

In March 1939 Koc went to London for the second time for negotiations to receive an export credit for his employer. Unofficially, he was working to maintain Poland's image in the United Kingdom, which was devastated by the annexation of Trans-Olza the previous year. Koc met representatives from the government and economists to prepare for the visit of the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Józef Beck.[117] Having returned, with Śmigły-Rydz's consent, Koc convinced the government to start talks about a material and a financial loan from the British. On 10 June 1939, Koc received informal instructions from Eugeniusz Kwiatkowski and was nominated as head of the official loan delegation to London.[117] Initially, the delegation estimated the need at £50-60 mln (approximately 1.24-1.49 bln zł), which was later reduced to £24 million (ca. 600 mln zł).[118] The talks were uneasy. The main problem within the Polish delegation was the question of sterling area accession, one of the conditions of the loan submission. Contrary to Kwiatkowski, Koc liked the idea of such a monetary union.[93] At the end, the Polish delegation did not manage to receive the loan in June 1939 (although talks were to be continued in autumn). The only money received from Britain before the war broke out was an £8 million materials loan on 2 August 1939.[119]

World War II (1939–1945)

[edit]Polish gold evacuation and escape to France

[edit]At the dawn of the September campaign, Koc was an advocate of the transfer of gold from Poland's reserves to finance the purchase of the military equipment needed by the Polish army. Two days after the conflict started, Koc asked Aleksander Litwinowicz, Vice-Minister of Military Affairs and chief of Army Administration, to be employed in the financial department of the General Staff, which the general accepted.[117] Koc was thereby reactivated in military service. Later, he coordinated preparations for the gold evacuation by bus from Warsaw.[120] He departed with one of the convoys on 5 September to Łuck, where he handed over the cargo to Ignacy Matuszewski and Henryk Floyar-Rajchman.[1]

On 10 September 1939, Koc was nominated by Mościcki as Vice-Minister of Treasury. The next day, Koc fled from Poland to Czerniowce. There, he, together with the ambassador of Poland in Bucharest, Roger Raczyński, tried to obtain permission to transit the gold via Romania. At the same time, Koc was ordered to terminate the British loan talks, in order to use the money for the military. A few days later, Koc moved to Bucharest, where he convinced Henryk Gruber, an important businessman, to send a request to the Powszechna Kasa Oszczędności (PKO) branch in New York City (or Paris) to pay him a 2 mln zł loan, which, apparently, was needed for the Army.[121] "Apparently" is used, because Koc did not inform the PKO about the purpose of this transaction, which was why it never happened.[122]

Having arrived to Paris (somewhere between 16 and 18 September[117][121][123]), Koc started organising the structures of the Polish Ministry of Treasury. At the time, the Polish government was interned and Mościcki had resigned, leaving Koc as the highest-ranking representative of the Polish government in France. For some time, he was part of the council acting as the government, together with the ambassador to France, Juliusz Łukasiewicz; Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs, Jan Szembek and Stanisław Burhardt-Bukacki.[5] Knowing that a coalition government was necessary, he kept contact with the opposition (for example, Władysław Sikorski).[124]

Work for Sikorski's government (1939–1941)

[edit]Minister of Industry and Trade and Minister of Treasury

[edit]On 30 September 1939, Koc, one of two piłsudskiites in Władysław Sikorski's cabinet (with August Zaleski, Minister of Foreign Affairs), became Minister of Treasury, his first ministerial post, and added the Minister of Industry and Trade ten days later.[125] While in Sikorski's cabinets, Koc was trying to preserve the nation's loans, gold, money and securities,[126] all of which was a problem because of the Polish government's legal status. In addition, Koc was attempting to help Polish refugees in Romania, France and Hungary. Koc tried to cut expenditures to the minimum (by e.g. giving out unpaid leaves to most government workers via a declaration on 10 October 1939),[127] in order to preserve as much gold as possible for post-war restoration.[127] His policy could be summed up as: "I will fly over the possessions as if I were a vulture".[128] At the same time, Koc was trying to minimise interest expenditures. To realise the policy, Koc convinced the British to give a £5 million loan, before completely spending the earlier £8 million loan.[129]

While in office, Ignacy Matuszewski became ensnared in a scandal. The colonel, while making a report on the gold transport, was criticised for inappropriate financial expenditures on services and some other minor "unnecessary" purchases, e.g. of headache powder.[130] Having heard the charges, Matuszewski attacked his friend Koc for his lack of reaction on them and then suggesting that Koc was the instigator of the criticism.[131]

Perhaps the worst attack, however, came from Stanisław Kot, Vice-PM in the Sikorski government and an ardent enemy to everything connected with the Sanation. Kot accused him of attempting to speculate on Polish loans, monopolizing the Polish export for Koc's own profit and influencing others in order to give more power to piłsudskiites. In addition, Kot tried to prove that Koc was wasting government money, for example, while giving £30 thousand in financial support to Aleksandra Piłsudska; Kot was also unhappy with the slow pace of Koc's work.[5] Koc thereupon resigned both of his offices, on 9 December 1939.[132]

II Vice-Minister of Treasury

[edit]Koc then served as II Vice-Minister of Treasury, most probably at the insistence of Henryk Strasburger. The work with the new Minister of Treasury did not cause problems for either party.[5] Koc was responsible for the organization of the military industry with the help of Polish immigrants in France (where the Polish government-in-exile was located). The action's purpose was to increase the resources of the government and to develop the Polish army, while helping the refugees to find jobs (in Turkey, if not in France).[5]

The disposition of Polish gold remained unresolved. The Bank of Poland wanted to transfer the gold from Beirut to either Great Britain or United States, a request which did not find support in the Treasury. Koc was later attacked by the Bank of Poland because he (presumably) was the only person in the ministry against gold evacuation[133] from North Africa, where it was trapped in the pro-German Vichy France colonies. The dispute cost Koc his position. Pragier suggests that Koc resigned "a few weeks before April 1940",[126] while Mierzwa proposes a later date when Sikorski's government was under reorganization.[5] Accepting the later version, another reason for Koc to leave the ministry was that he evacuated from France too early (on 18 June 1940 from Bordeaux, aboard on HMS "Nylon").[134] Three days later, Koc welcomed Władysław Raczkiewicz, President of Poland, on London Paddington, a fact recorded in his diary.[135]

Polish gold vindication

[edit]Already in Great Britain, after Raczkiewicz convinced Sikorski that Koc was innocent in the gold reserves loss,[5] Koc was given the mission of Polish gold vindication, which had relocated to Dakar. As Vichy France was a puppet state of the Axis, it was impossible to get permission to transport gold outside the French colonies from either Nazi Germany or Italy. At the same time, the Bank of France possessed gold reserves in New York worth a few hundred million dollars. Thus, Koc decided to convince the US to confiscate the French reserves while seeking an immediate loan (since the Polish gold could not be returned yet).[5] He sent to assess the possible engagement of American financial institutions in his country's future reconstruction.

In mid-September 1940, Koc sailed out of Liverpool to the US, arriving in early October. There, he revealed that Belgian officials had also requested confiscation of the French gold. Koc was named head of the Gold Vindication Committee, a nomination protested by Henryk Strasburger, Minister of Treasury, and Bohdan Winiarski, a right-wing politician and then head of the Bank of Poland. In June 1941, Sikorski suspended the committee's activity.[5]

Later life

[edit]After the war, he became a chef at a pension in Sea Cliff, New York and at the Waldorf Astoria New York. He also served on the board of the Józef Piłsudski Institute of America.

Koc died on 3 February 1969 in New York. He was buried in grave L2-245 at Wolvercote Cemetery in England; his symbolic grave (marked kw. A12-7-29) is located in Warsaw's Powazki Cemetery

Honours and awards

[edit]- Silver Cross of the Virtuti Militari

- Officer's Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta

- Cross of Valour – four times

- Cross of Independence

- Officer's Star "Parasol"

- Officer's Cross of the Legion of Honour (France)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Koc, Adam (2005). Wspomnienia. Wrocław: Towarzystwo przyjaciół Ossolineum. pp. 8–10. ISBN 83-7095-080-9.

- ^ Morawski, Wojciech (1998). Słownik historyczny bankowości polskiej do 1939 roku [The historical dictionary of Polish banking until 1939] (PDF) (in Polish). Fundacja Bankowa im. Leopolda Kronenberga; Muza. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- ^ "Adam Koc". PORTAL 1920 (in Polish). Retrieved 2024-08-23.

- ^ a b c Milek, Jerzy. "Głos Prawdy ma nowego Naczelnego Redaktora" ["Głos Prawdy" newspaper has its new editor-in-chief] (in Polish). Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai Mierzwa, Janusz (2006). Pułkownik Adam Koc. Biografia polityczna [Colonel Adam Koc. A political biography.]. Studia z Historii XX Wieku (in Polish). Cracow: Historia Iagellonica. ISBN 83-88737-33-3.

- ^ a b c d "Parlamentarzyści – Pełny opis rekordu – Koc Adam Ignacy". bs.sejm.gov.pl (in Polish). Bibiloteka Sejmowa. Retrieved 2017-07-11.

- ^ a b Laskowski, Otton, ed. (1934). Encyklopedia Wojskowa. Warsaw. pp. 298–299.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Skłodowski, Krzysztof (1999). Dzisiaj ziemia wasza jest wolna. O niepodległość Suwalszczyzny [Today your land is free. On the independence of Suwałki region.] (in Polish). Suwałki: Muzeum Okręgowe w Suwałkach. p. 12.

- ^ "Historia szkoły" [The history of school] (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2017-07-21. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ^ a b Rokicki, Cz. (1938). "Rewolucyjna młodzież narodowa". Niepodległość. XVIII: 272–277.

- ^ a b Miedziński, Bogusław (1976). Moje wspomnienia (3) [My memories (3)] (in Polish). Vol. 35. Paris: Zeszyty Historyczne. pp. 98–99, 112–113.

- ^ a b c d e Wrzos, Konrad (13 Feb 1936). "Z żołnierza – dziennikarz, z dziennikarza – skarbowiec" [From a soldier to a journalist, from a journalist to an economist]. polona.pl (in Polish). Warsaw: Polska Zbrojna. pp. 1, 5. Retrieved 2018-01-30.

- ^ Brzozowski, W. (11 November 1934). "Powstanie i pierwszy rok pracy POW" [The creation and the first year of POW's activity]. Strzelec (in Polish) (45): 7.

- ^ Jędrzejewicz, Wacław (1981). Kronika życia Józefa Piłsudskiego 1867-1935 [The chronicles of Józef Piłsudski's life 1867–1935] (in Polish). London: Polska Fundacja Kulturalna. p. 297.

While describing the scene of promotion, Koc is forgotten, but information is present in [3] that Koc was as well promoted.

- ^ "Military History Online - The Great Retreat, Eastern Front 1915". www.militaryhistoryonline.com. Retrieved 2017-07-10.

- ^ Starzyński, Roman (2012) [1937]. Cztery lata wojny w słuźbie Komendanta: Prezeźycia wojenne 1914-1918. Warsaw: Tetragon, Instytut Wydawniczy "Erica". p. 288. ISBN 978-83-63374-04-4.

- ^ Święcicki, T. (1971). Ze wspomień o Adamie Kocu [On the memories about Adam Koc] (in Polish). Vol. VIII. London: Niepodległość. pp. 177–178.

- ^ Składowski, Felicjan Sławoj (1938). Benjaminów: 1917–1918 (in Polish). Warsaw: Instytut Józefa Piłsudskiego poświęcony badaniu najnowszej historii Polski [Józef Piłsudski Institute for newest Polish history research.]

- ^ "Płk Adam Koc" [Colonel Adam Koc]. Myśl Konserwatywna (in Polish). 2016-08-31. Retrieved 2017-07-11.

- ^ Adamczyk, Arkadiusz (2000). Bogusław Miedziński (1891-1972). Biografia polityczna. Toruń: A. Marszałek. p. 39.

- ^ Jabłonowski, Marek; Stawecki, Piotr (1998). Następca Komendanta Edward Rydz-Śmigły. Materiały do biografii [The Successor of Commandant[-in-Chief] Edward Rydz-Śmigły] (in Polish). Pułtusk: Wyższa Szkoła Humanistyczna. p. 42.

- ^ Lipiński, Wacław (1935). Walka zbrojna o niepodległość Polski 1905-1918. Warsaw. p. 179.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Pepłoński, Andrzej (1999). Wywiad w wojnie polsko-bolszewickiej 1919-1920 [Intelligence services in the Polish–Soviet war 1919–1920] (in Polish). Warsaw: Bellona. p. 43.

- ^ "Dziennik Rozkazów, 1920". Dziennik Rozkazów (in Polish). Ministerstwo Spraw Wojskowych: 1–2. 17 January 1920 – via Śląska Biblioteka Cyfrowa.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Centralne Archiwum Wojskowe (CAW), Akta personalne i odznaczeniowe płk. Adama Koca, columns 2-3

- ^ "Dekrety i rozkazy Naczelnego Wodza: Kapituła tymczasowa orderu "Virtuti Militari"" [Decrees and orders of the Chief Commandant: The temporary Chamber of "Virtuti Militari" order]. Dziennik rozkazów (in Polish). 1 (1): 1–2. 17 January 1920 – via Biblioteka Śląska w Katowicach.

- ^ Centralne Archiwum Wojskowe (CAW), Oddział II Sztabu Generalnego, sign. I.303.4, vol. 11, n/p

- ^ a b Filipow, Krzysztof (1990). Order Virtuti Militari: 1792–1945 (in Polish). Warsaw: Bellona. ISBN 8311077894.

- ^ Majchrowski, Jacek (1994). Kto był kim w drugiej Rzeczypospolitej [Who was who in the II Polish Republic] (in Polish). Vol. II. Warsaw: Polska Oficyna Wydawnicza "BGW". ISBN 83-7066-569-1.

- ^ Letter of A. Koc to the Commandant-in-Chief, dated 10 June 1920. Archiwum Aktów Nowych, The collection of the remains of the material of the II Department, vol. 144, columns 13-22.

- ^ "Dziennik Personalny Ministerstwa Spraw Wojskowych Nr 23 z 23 czerwca 1920 roku, poz. 595". Dziennik Personalny Ministerstwa Spraw Wojskowych (in Polish). 23. 23 June 1920.

- ^ Marszałek, Piotr Krzysztof (1995). Rada Obrony Panstwa z 1920 roku: studium prawnohistoryczne (in Polish). Wrocław: Wrocław University. ISBN 9788322912140.

- ^ a b Wyszczelski, Lech (1997). Warsaw 1920 (in Polish). Warsaw: Bellona. ISBN 8311083991.

- ^ Wojtycza, Janusz (2001). Przysposobienie wojskowe w odrodzonej Polsce do roku 1926 [The military preparation in the newly-born Poland until 1926] (in Polish). Kraków: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Akademii Pedagogicznej. p. 32. ISBN 9788372711250.

- ^ Koc, Adam (15 May 1921). "Międzynarodowy Związek Strzelecki". Rząd i Wojsko.

- ^ Koc, Adam (1921). "W sprawie "Międzynarodowego Związku Strzeleckiego"" [On the "International Riflemen's Association"]. Bellona (in Polish). 6: 522–523.

- ^ Rocznik oficerski 1923 (in Polish). Warsaw: Ministerstwo Spraw Wojskowych. 1923.

- ^ "Lista starszeństwa oficerów zawodowych. Załącznik do Dziennika Personalnego Ministerstwa Spraw Wojskowych" [List of seniority of officers. Annex to the "Dziennik Personalnego Ministerstwa Spraw Wojskowych".]. Dziennik Personalny Ministerstwa Spraw Wojskowych (in Polish) (13). Warsaw: Zakłady Graficzne Ministerstwa Spraw Wojskowych: 24. 8 June 1922.

- ^ Koper, Sławomir (2011). Afery i skandale Drugiej Rzeczypospolitej (in Polish). Warsaw: Bellona. p. 260. ISBN 9788311120464.

- ^ Lisiewicz, M. (1954). Związek Wojskowy "Honor i Ojczyzna" ["Honor i Ojczyzna" military association] (in Polish). Vol. 3. Warsaw: Bellona. p. 51.

- ^ Chajn, Leon (1984). Polskie wolnomularstwo 1920-1938 [Polish freemasonry of 1920–1938] (in Polish). Warsaw: Czytelnik. p. 161. ISBN 978-83-85333-32-6. (reprint by AKME)

- ^ Adam Warmiński (1921). Wiersze i proza. Warsaw: Ignis.

- ^ Ruszczyc, Marek (1987). Strzały w Zachęcie [Shooting in Zachęta] (in Polish). Katowice: Śląsk. p. 185.

- ^ a b c Miedziński, Bogusław (1972). "Sprostowania zza grobu". Zeszyty Historyczne (in Polish). 22.

- ^ a b Rocznik oficerski 1924 [Officers' Annals 1924] (in Polish). Warsaw: Ministerstwo Spraw Wojskowych. 1924. pp. 39, 133, 340.

- ^ "Dziennik Personalny Ministerstwa Spraw Wojskowych Nr 17 z 14 lutego 1925 roku". Dziennik Personalny Ministerstwa Spraw Wojskowych (in Polish). Ministerstwo Spraw Wojskowych: 75. 14 February 1925.

- ^ "Parlamentarzyści – Pełny opis rekordu". bs.sejm.gov.pl.

- ^ "Kosciuszko Lodge No.1085, Free and Accepted Masons, New York". www.kosciuszkomason.com.

- ^ Hass, Ludwik (1984). Ambicje, rachuby, rzeczywistość: Wolnomularstwo w Europie Środkowo-Wschodniej 1905–1928 [Ambitions, calculations and reality: Freemasonry in Central-East Europe of 1905–1928] (in Polish). Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. ISBN 8301038241.

- ^ Hass, Ludwik (1992). Skład osobowy wolnomularstwa polskiego w II Rzeczypospolitej (Wielka Loża Narodowa) [A personal list of Polish freemasonry in II Polish Republic (from the National Great Lodge)] (in Polish). Warsaw: Przegląd Historyczny.

- ^ a b Garlicki, Andrzej (1979). Przewrót majowy [The May Coup] (in Polish). Warsaw: Czytelnik. p. 142.

- ^ Drozdowski, Marian Marek (1979). Sprawy i ludzie Drugiej Rzeczypospolitej [The affairs and personalities of the Second Polish Republic] (in Polish). Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie. p. 135.

- ^ "Dziennik Personalny Ministerstwa Spraw Wojskowych Nr 37 z 14.06.1926 r". Dziennik Personalny Ministerstwa Spraw Wojskowych (in Polish) (37). 14 September 1926.

- ^ "Dziennik Personalny Ministerstwa Spraw Wojskowych Nr 8 z 21.03.1928 r.". Dziennik Personalny Ministerstwa Spraw Wojskowych (in Polish) (8): 87. 21 March 1928.

- ^ Romeyko, Marian (1967). Przed i po Maju [Before and after May [1926]] (in Polish). Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Ministerstwa Obrony Narodowej. p. 558. ISBN 83-11-06884-4.

- ^ Stradecki, Józef (1974). "Funkcje społeczne satyry ("Cyrulik Warszawski", 1926–1934)" [The social functions of satire ("Cyrulik Warszawski", 1926–1934)]. In Żółkiewski, Stefan; Hopfinger, Maryla; Rudzińska, Kamila; et al. (eds.). Społeczne funkcje tekstów literackich i paraliterackich [The social functions of the literary and paraliterary texts] (in Polish). Wrocław, Warsaw, Kraków: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich. p. 169.

- ^ "Dziennik Personalny Ministerstwa Spraw Wojskowych Nr 9 z 26.04.1928 r.". Dziennik Personalny Ministerstwa Spraw Wojskowych (in Polish) (9): 176. 26 April 1928.

- ^ "Dziennik Personalny Ministerstwa Spraw Wojskowych Nr 8 z 31.03.1930 r.". Dziennik Personalny Ministerstwa Spraw Wojskowych (in Polish) (8). 31 March 1930.

- ^ a b c Kaszuba, Elżbieta (2004). System propagandy państwowej obozu rządzącego w Polsce w latach 1926–1939 [The system of state propaganda of the ruling party in post-May Coup Poland (1926–1939)] (in Polish). Toruń: Adam Marszałek. p. 17. ISBN 9788373228771.

- ^ Filipow, Krzysztof (1998). Krzyż i Medal Niepodległości (in Polish). Białystok: Ośrodek Badań Historii Wojskowej, Muzeum Wojska. p. 8. ISBN 83-86232-90-0.

- ^ Chojnowski, Andrzej (1986). Piłsudczycy u władzy. Dzieje Bezpartyjnego Bloku Współpracy z Rządem [Piłsudskiites at power. The history of BBWR] (in Polish). Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich. p. 170. ISBN 83-04-02293-1.

- ^ Czubiński, Antoni (1962). Centrolew: Kształtowanie się i rozwój demokratycznej opozycji antysanacyjnej w Polsce w latach 1926–1930 ["Centrolew" [centre-left opposition]. Creation and development of democratic antisanational opposition in 1926–1930 Poland] (in Polish). Poznań: Wydawnictwo Poznańskie. p. 25.

- ^ Koc, Adam (30 October 1929). "Od wydawnictwa" [From the staff]. Gazeta Polska (in Polish). 1 (1): 1 – via Polona.

- ^ "Spór o Nieśwież" [A controversy of Nesvizh]. Głos Prawdy (in Polish). 8: 1. 2 February 1929.

- ^ "Zjazd byłych członków POW" [The meeting of former POW members]. Strzelec (in Polish): 5–6. 24–30 March 1929.

- ^ "Nowy wiceminister skarbu pos. Adam Koc" [New vice-minister of Treasury: MP Adam Koc]. polona.pl (in Polish). Gazeta Polska. 24 December 1930. p. 2. Retrieved 2017-07-12.

- ^ Katelbach, T. (1969). "Szlachetny" (Wspomnienie o Adamie Kocu) ["Szlachetny" (Memories about Adam Koc)] (in Polish). Vol. 16. Paris. p. 172.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Zdanowski, Juliusz (2016). Dziennik. Vol. VII. Szczecin: Minerwa. p. 276. ISBN 978-83-64277-48-1.

- ^ "Wiceminister skarbu p. A. Koc – komisarzem rządowym w Banku Polskim" [Vice-minister of Treasury Adam Koc [is] the State commissioner for the Bank of Poland]. polona.pl (in Polish). Gazeta Polska. 3 January 1932. Retrieved 2017-07-12.

- ^ "Dzień polityczny" [Political day]. polona.pl (in Polish). Gazeta Polska. 27 March 1931. p. 2. Retrieved 2017-07-12.

- ^ "Po zapałkach – węgiel". Gazeta Warszawska (in Polish) (380): 7. 31 December 1930.

- ^ "Pożyczka pod zastaw kolei?!" [A loan as a railroad mortgage?!]. Robotnik (in Polish) (376): 3. 4 December 1930.

- ^ Sokołów, Floryan (8 July 1933). "Pożyczka angielska na elektryfikację węzła warszawskiego" [A British loan for Warsaw rail knot electrification]. Gazeta Polska (in Polish): 1 – via Polona.

- ^ Sokołów, Floryan (3 August 1933). "Podpisanie pożyczki angielskiej" [British loan signed]. Gazeta Polska (in Polish): 1 – via Polona.

- ^ Grobelny, Michał (2016). Jak w II RP kolej budowali [How railroads were built in the Second Polish Republic] (in Polish). Warsaw: Rynek Kolejowy. p. 84. ISBN 978-0016441950.

- ^ Sokołów, Floryan (26 April 1934). "Znaczenie tranzakcji kredytowej z Tow. "Westinghouse": Wywiad specjalny u ministra Adama Koca" [The significance of loan transaction with "Westinghouse" enterprise. Special interview with [vice-]minister Adam Koc]. Gazeta Polska (in Polish): 1 – via Polona.

- ^ Sokołów, Floryan (16 June 1933). "Pierwsze rozdźwięki w Londynie" [The first news from London]. Gazeta Polska (in Polish) (162): 2.

- ^ Sokołów, Floryan (4 July 1933). "Deklaracja państw "złotych"" [The declaration of "golden" countries]. Gazeta Polska (in Polish): 2 – via Polona.

- ^ Wyszczelski, Lech (2010). Generał Kazimierz Sosnkowski (in Polish). Warsaw: Bellona. pp. 159–160. ISBN 978-83-11-11942-0.

- ^ Franaszek, Antoni (2008-05-01). "POZNAJ HISTORIĘ OJCZYSTEGO KRAJU: Obóz sanacyjny po śmierci Piłsudskiego" [Get to know the history of your homeland: Sanational camp after Piłsudski's death] (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2008-05-01. Retrieved 2017-07-13.

- ^ Garlicki, Andrzej (2007). Orzeł Biały na osłodę [The White Eagle as solace] (in Polish). Warsaw: Polityka.

- ^ Roszak, Stanisław; Kłaczkow, Jarosław (2015). Poznać przeszłość – wiek XX. Podręcznik do historii dla szkół ponadgimnazjalnych. Poziom podstawowy [To know the past – XX century. History textbook for after-gymnasium schools. Basic level] (in Polish). Warsaw: Nowa Era. ISBN 9788326724022.

- ^ Zieleniewski, Leon (1899–1940) (1936). Sejm i Senat 1935-1940: IV kadencja [Sejm and Senate of the IV cadency : 1935–1940] (in Polish). Warsaw: Księgarnia F. Hoesicka. p. 177.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Minister A. Koc u prezydenta Roosevelta" [[Vice-]minister A. Koc on [meeting] with President Roosevelt]. Gazeta Polska (in Polish): 2. 27 September 1935 – via Polona.

- ^ Faryś, Janusz; Pajewski, Janusz (1991). Gabinety Drugiej Rzeczypospolitej [The cabinets of the Second Polish Republic] (in Polish). Szczecin: Likon.

- ^ Woźniak, Michał. "Nasz patron" [Our patron [Eugeniusz Kwiatkowski]]. www.zsp2jarocin.pl (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2017-06-17. Retrieved 2017-07-13.

- ^ Wareński, Aleksander (17 February 1936). "Pożegnanie prezesa A. Koca" [Farewell [for] Head [of the Bank of Poland] A. Koc]. Gazeta Lwowska (in Polish): 2 – via Jagiellonian Digital Library.

- ^ Korob-Kucharski, Henryk (8 February 1936). "Wiceminister Adam Koc prezesem Banku Polskiego" [Vice-minister Adam Koc is Head of the Bank of Poland]. Gazeta Polska (in Polish): 1 – via Polona.

- ^ Jezierski, A.; Leszczyńska, C. (1994). Bank Polski S.A. 1924-1951 (in Polish). Warsaw: Narodowy Bank Polski. pp. 43–44.

- ^ Matuszewski, Ignacy (9 May 1936). "Minister Adam Koc ustąpił z prezesury Banku Polskiego" [[Vice-]minister Adam Koc resigned as Head of the Bank of Poland]. Gazeta Polska (in Polish): 1 – via Polona.

- ^ "Bank Polski przeznacza 20 milj. na natychmiastowe zatrudnienie bezrobotnych" [Bank of Poland gives 20 million [złotych] for immediate employment of the unemployed]. Gazeta Polska (in Polish): 2. 26 April 1936 – via Polona.

- ^ Feinstein, Charles H. (1995-09-28). Banking, Currency, and Finance in Europe Between the Wars. Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780191521669.

- ^ a b Morawski, Wojciech (1998). Słownik historyczny bankowości polskiej do 1939 roku [Banking historical dictionary until 1939] (PDF) (in Polish). Warsaw: Fundacja Bankowa im. Leopolda Kronenberga, Muza.

- ^ Wareński, Aleksander (1 November 1935). "Rozwiązanie Bezpartyjnego Związku Współpracy z Rządem. Przemówienie płk. Walerego Sławka" [Nonpartisan Bloc for Cooperation with the Government dissolved. Colonel Walery Sławek's speech]. Gazeta Lwowska (in Polish) (251): 3 – via Jagiellonian Digital Library.

- ^ "Samobójstwo Premiera – życie i śmierć Walerego Sławka" [Prime Minister's suicide – the life and death of Walery Sławek]. Józef Piłsudski I jego czasy (in Polish). 2 April 2014. Retrieved 2017-07-14.

- ^ "Deklaracja ideowa obozu płk Koca" [The ideological manifesto of the colonel Koc's camp]. Dziennik Poznański (in Polish). 79 (43): 1–2. 22 February 1937 – via Greater Poland Digital Library.

- ^ a b c d e f Ajnenkiel, Andrzej (1980). Polska po przewrocie majowym. Zarys dziejów politycznych Polski 1926–1939 [Poland after the May Coup. A sketch of Polish political activity in 1926–1939] (in Polish). Warsaw: Wiedza Powszechna. pp. 543–6, 572, 577–8.

- ^ a b Majchrowski, Jacek (1985). Silni – zwarci – gotowi: myśl polityczna Obozu Zjednoczenia Narodowego. Warsaw: PWN. ISBN 83-01-05323-2.

- ^ Jędruszczak, Tadeusz (1963). Piłsudczycy bez Piłsudskiego. Powstanie Obozu Zjednoczenia Narodowego w 1937 roku [Piłsudskiites without Piłsudski. Creation of the Camp of National Unity in 1937.] (in Polish). Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. p. 102.

- ^ "Jutro pułk. Adam Koc ogłosi deklarację polityczną" [Colonel Adam Koc is going to announce a political declaration tomorrow]. Gazeta Lwowska (in Polish): 1. 21 February 2017 – via Jagiellonian Digital Library.

- ^ Baumgarten, Murray; Kenez, Peter; Thompson, Bruce Allan (2009). Varieties of Antisemitism: History, Ideology, Discourse. Newark: University of Delaware Press. pp. 172–174. ISBN 978-0-87413-039-3.

- ^ "Uwagi o przemówieniu płk Koca" [Remarks on the colonel Koc's speech]. Kurier Poznański (in Polish). 32 (85): 1. 22 February 1937 – via Greater Poland Digital Library.

- ^ "Deklaracja ideowo-polityczna wygłoszona dn. 21 b. n. przez płk Adama Koca" [An ideological declaration from 21 [February], announced by colonel Adam Koc]. polona.pl (in Polish). Gazeta Polska. 22 February 1937. pp. 1–2, 4. Retrieved 2017-07-14.

- ^ a b c d "Wywiad u pułkownika Adama Koca" [Interview with colonel Adam Koc]. Gazeta Lwowska (in Polish). 127 (247): 1, 3. 29 October 1937 – via Jagiellonian Digital Library.

- ^ a b c d e f Przeperski, Michał (24 October 2012). "Polska "noc długich noży"" [The Polish [version] of "Night of the Long Knives"]. histmag.org (in Polish). Retrieved 2017-07-14.

- ^ "Szef Związku Młodej Polski wykluczony z OZN: mianowanie nowego kierownika I władz zarządu" [Head of the Union of Young Poland expelled from OZN: nomination of new director and new council of the organisation]. Gazeta Lwowska (in Polish). 128 (90): 1. 22 April 1938 – via Jagiellonian Digital Library.

- ^ a b "Zamach bombowy na płk Koca: Sprawca zamachu rozszarpany przez eksplodującą bombę" [A bomb assassination attempt on colonel Koc: the assassinator torn apart by the explosion]. Ilustrowany Kuryer Codzienny (in Polish). 27 (199): 3. 19 July 1937 – via Lesser Poland Digital Library.

- ^ Antoniewicz, Zdzisław (20 April 1937). "Nieudany zamach na płk Adama Koca?" [A failed attempt to assassinate colonel Adam Koc?]. Kurier Poznański (in Polish). 32 (322): 1 – via Greater Poland Digital Library.

- ^ "Nieudany zamach bombowy na płk Koca" [A failed bomb murder attempt on colonel Koc]. Gazeta Polska (in Polish). 9 (198): 1. 19 July 1937 – via Polona.

- ^ "Ujawnienie nazwiska sprawcy zamachu na płk. Adama Koca" [Revealing the name of an assassination attempt culprit on colonel Adam Koc]. Gazeta Polska (in Polish). 9 (208): 1. 29 July 1937 – via Polona.

- ^ "Środowisko, które musi być zniszczone po zamachu na pułk. Adama Koca" [The organisation that has to be destroyed after an assassination attempt on colonel Koc]. Gazeta Lwowska (in Polish). 127 (167): 1. 21 July 1937.

- ^ a b c d Brakoniecki, Bożydar (18 July 2014). "Sanacyjna "noc długich noży". Plan Śmigłego i niedoszły zamach stanu w 1937 roku" [Sanational "Night of the Long Knives". The plans of Śmigły and the coup d'état that did not happen, in 1937]. Polskatimes.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 2017-07-14.

- ^ Wynot, Edward D Jr. (1974). Polish Politics in Transition: The Camp of National Unity and the Struggle for Power, 1935-1939. Athens (GA): University of Georgia Press. p. 179.

- ^ "Zmiana na stanowisku szefa O. Z. N." [A shift on the head of OZN position]. Gazeta Lwowska (in Polish). 128 (7): 1. 12 January 1938 – via Jagiellonian Digital Library.

- ^ Archiwum Akt Nowych. Chapter: ZLP (Związek Legionistów Polskich). Volume 152

- ^ Landau, Zbigniew; Tomaszewski, Jerzy (1995). Bank Handlowy w Warszawie S.A. Zarys dziejów 1870-1995 [Bank Handlowy w Warszawie S.A. A sketch of activity from 1870–1995] (in Polish). Warsaw: Muza S.A.

- ^ a b c d Koc, Adam. Rok 1939 (luty-wrzesień) (in Polish). Vol. III. pp. 23, 44–45, 77, 115.

- ^ "Spuścizna...". Biuletyn. Polski Ośrodek Społeczno-Kulturalny (BPOSK): 14.

- ^ Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum (London). Collection 82, vol. 18, cards 68–70

- ^ Łazor, Jerzy (10 March 2014). "Od Grabskiego do Kwiatkowskiego. Kredyt w Drugiej Rzeczypospolitej" [From Grabski to Kwiatkowski. Credit in the Second Polish Republic.] (PDF). Mówią wieki (in Polish).

- ^ a b Kirkor, S. (1971). Ewakuacja Ministerstwa Skarbu w 1939 (ze wspomnień osobistych) [The evacuation of the Ministry of Treasury in 1939 (from personal memories)] (in Polish). Vol. 20. Paris: Zeszyty Historyczne. pp. 114–115.

- ^ Gruber, Henryk (1968). Wspomnienia i uwagi. London: Gryf Publications. pp. 363, 402.

- ^ Mühlstein, Anatol (1999). Dziennik. Wrzesień 1939-listopad 1940. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN. p. 43. ISBN 9788301127701.

- ^ Szembek, Jan (1989). Diariusz. Wrzesień-grudzień 1939 [Diary. September–December 1939] (in Polish). Warsaw: P.A.X. p. 73.

- ^ Kunert, Andrzej Krzysztof; Walkowski, Zygmunt (2005). Kronika kampanii wrześniowej 1939. Warsaw: Edipresse Polska. p. 132. ISBN 83-60160-99-6.

- ^ a b Pragier, Adam (1964). Czas przeszły dokonany (in Polish). London. pp. 566, 580.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Zgórniak, Marian; Rojek, Wojciech; Suchcitz, Andrzej, eds. (1994). Protokoły z posiedzeń Rady Ministrów Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej [The Protocols from the Council of Ministers of the [Second] Polish Republic sessions] (in Polish). Kraków: Secesja. pp. 17–21.

- ^ Sokolnicki, Michał (1948). "Dziennik ankarski" [The Ankara diary]. Kultura (in Polish). 4: 107.

- ^ List from Adam Koc to Kazimierz Sosnkowski, from 23 July 1943 (New York City)

- ^ Cat-Mackiewicz, Stanisław (1993). Historia Polski od 17 września 1939 do 5 lipca 1945 (in Polish). London: Puls. pp. 52–53. ISBN 1859170072.