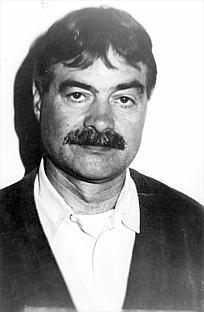

Benedetto Santapaola

Benedetto Santapaola | |

|---|---|

Nitto Santapaola | |

| Born | 4 June 1938 |

| Other names | Il Cacciatore ("The Hunter") |

| Occupation | Mafioso |

| Criminal status | Imprisoned since 1993 |

| Children | 3 |

| Allegiance | Corleonesi clan Ties with 'Ndrangheta ('Ndrina of Melito di Porto Salvo) |

| Conviction(s) | Mafia association, multiple murder |

| Criminal charge | Mafia association, multiple murder |

| Penalty | Life imprisonment |

Benedetto Santapaola (Italian pronunciation: [beneˈdetto santaˈpaːola]; born 4 June 1938), better known as Nitto, is a prominent Italian mafioso from Catania, the main city and industrial centre on Sicily's east coast. His nickname is il Cacciatore ("The Hunter") because of his passion for shooting game.

Early years

[edit]Nitto Santapaola was born in the degraded neighbourhood of San Cristoforo,[1] in Catania, into a poor family together with his brothers Salvatore, Antonino, Natale and numerous cousins, such as the Ferrera clan, the Ercolano clan and the Romeo clan, all members or associates of Cosa Nostra, and the future nucleus of the Santapaola-Ercolano Mafia family.

At the beginning of the 1960s, Santapaola was introduced by his cousin Francesco Ferrera into the largest Mafia family of Catania, at the time under the command of Giuseppe Calderone. Santapaola's first denunciation was in 1962 for theft and criminal conspiracy. In 1970 he was sent into internal exile and in 1975 he was denounced for cigarette smuggling.

Ally of the Corleonesi

[edit]While Giuseppe Calderone was elevated to the Regional Commission of Cosa Nostra in 1975, his underboss Santapaola took over the illicit business in Catania for the Mafia family and became the capo famiglia of the clan. Santapaola managed the interests in heroin trafficking and acted as chief enforcer for the leading businessmen. Meanwhile, he carefully built a private faction within the family that was loyal to him – and strengthened relations with Totò Riina and the Corleonesi.

While Riina was a fugitive, he frequently spent time in and around Catania and often went hunting with Santapaola around the local mountains. Riina decided to support Santapaola's faction in order to replace Calderone, an ally of Stefano Bontade from Palermo and Giuseppe Di Cristina from Caltanissetta. Giuseppe Calderone was killed on 8 September 1978 by his former close friend, Santapaola. Santapaola took over the command of the Catania Mafia Family. These skirmishes were just a prelude to the Second Mafia War that really started after the murder of Stefano Bontade in 1981.

Catania Mafia wars

[edit]

Santapaola's command over the Catania Mafia was not unchallenged. He had to fight a war against another independent group that was not part of the Mafia in Catania, known as Cursoti, which waged war in order to control gambling and cigarette smuggling. He was also involved in a bitter feud with the faction of Alfio Ferlito, who had been a close friend of Giuseppe Calderone. The war involved gun battles in the streets and dozens of murders.[2][3]

On 6 June 1981 and on 26 April 1982, Santapaola was seriously wounded when ambushed by Ferlito and his men. When Ferlito was arrested, Santapaola planned his revenge. On 16 June of the same year, Ferlito was killed in an ambush when he was being escorted by the Carabinieri during a transfer between two prisons, the Circonvallazione massacre. The gunmen were from Totò Riina.

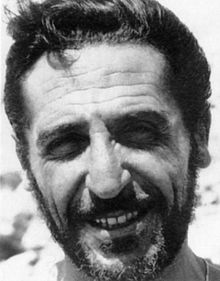

The murder of General Dalla Chiesa

[edit]Santapaola paid back the service by sending a hit team from Catania to Palermo to kill Carabinieri general Carlo Alberto Dalla Chiesa, his wife Emanuela Setti Carraro and the escort agent Domenico Russo on 3 September 1982, in the Via Carini in Palermo. Swapping hit teams proved to be a successful way to distract police investigations. Dalla Chiesa had just been appointed prefect of Palermo to end the violence that was the result of a war between rival Mafia families. In his last public interview, it had become clear that Dalla Chiesa had started to focus on the emerging role of the Catania Mafia.

Dalla Chiesa had noticed that four mighty real estate developers that dominated the construction industry on Sicily were building in Palermo with the consent of the Mafia. The four entrepreneurs, Carmelo Costanzo, Francesco Finocchiaro, Mario Rendo and Gaetano Graci, were granted the honorary title Cavaliere del Lavoro (Knight of Labour) by the Italian government as a reward for special merit to the Italian economy.

Links with business and politics

[edit]After Dalla Chiesa's murder, investigating magistrate Giovanni Falcone found a note that indicated that Dalla Chiesa had discovered that Santapaola was on the payroll of Costanzo. Falcone encouraged Colonel Elio Pizzuti of the Italian Financial/Customs Police (Guardia di Finanza) to look into their financial records. Pizzuti found ample evidence of corruption and political influence peddling by the four Knights that tied together the local Mafia, high finance and political figures.[4]

Santapaola had been a guest at the wedding of Costanzo's nephew and had been hiding in one of Costanzo's luxury hotels near Catania. He also had access to the private game reserve of another one of the Knights, Gaetano Graci. Mario Rendo bought all his cars from Santapaola's car dealership, while wiretaps revealed Rendo's executives discussing subcontracting with various mafiosi.

Pizzuto also discovered a massive tax fraud by the Knights through phoney receipts and a list of payoffs to politicians and magistrates. Rendo told inspectors that the false receipts were necessary to create a slush fund for government contracts. (A prelude to the scandal of political bribery known as Tangentopoli that would emerge ten years later in 1992.) Rendo discussed the investigations of Pizzuti with his boss, Treasury minister Rino Formica of the Italian Socialist Party (PSI). Pizzuti was promoted and sent to Triest in North Italy – as far away as possible from Sicily.

Later, photographs turned up showing the mayor and members of the Catania city council with Santapaola, while a clan war bloodied the streets at the time. One picture showed Santapaola in a friendly embrace with Salvatore Lo Turco, a member of the Sicilian parliament's Antimafia Commission.[5]

The Catanese Mafia was generally able to learn about arrest warrants before they were issued and sometimes have names crossed off the list. The police released Santapaola after only a few routine questions when his bulletproof car had been found at the scene of a vicious shoot-out in which several people had been killed. Moreover, they continued to grant him a license to bear arms, despite his well-known criminal record.[6]

Ties with the 'Ndrangheta

[edit]Santapaola had strong ties with some 'Ndrangheta clans, in particular with Natale Iamonte, the head of the Iamonte 'Ndrina based in Melito di Porto Salvo on the Ionic coast of Calabria. Iamonte and his ally Paolo De Stefano secured arms and drug transports when the harbour of Catania was controlled too strictly.[7][8] In return Santapaola helped the Iamonte clan to get subcontracts for the construction of rail works with the Costanzo firm.[9]

Murder of Giuseppe Fava

[edit]

Santapaola has been convicted for the murder of the journalist Giuseppe Fava on 5 January 1984. Fava, founder and editor-in-chief of the magazine I Siciliani, exposed the links between the Catania Mafia and the world of business and politics. In the first edition of I Siciliani Fava published an article I quattro cavalieri dell'apocalisse mafiosa (The four horsemen, or knights, of the Mafia apocalypse), denouncing the links of the entrepreneurs with the Mafia.[10]

In 1994, Maurizio Avola, a nephew of Santapaola, confessed to the killing of Fava, and became a pentito. He also confessed to some 70 other murders. Avola said that his uncle Nitto Santapaola had ordered the killing of the journalist.[11]

Arrest and life convictions

[edit]On 17 December 1987, Santapaola was convicted in absentia to life imprisonment as part of the Maxi Trial for the murder of Ferlito.[12] On 18 May 1993, he was arrested in a farmhouse hideout outside Catania after being on the run for 11 years.[13] His wife, Carmela Minniti, was killed on 1 September 1995, by a pentito for revenge of Santapaola posing as a policeman. They called at her house, pushed past her daughter and shot her dead.[14] "She ran his affairs," said Liliana Madeo, author of a book on the Mafia's new women. "If she was just a little woman, she wouldn't have been killed."[15]

Santapaola's rival Giuseppe Ferone (who had become a pentito) was one of the killers. Nitto Santapaola forgave his wife's killer in a letter he publicly read in court. Ferone's son and father had been killed on the orders of Santapaola.

In 1998, Santapaola and Aldo Ercolano were convicted for ordering the killing of Giuseppe Fava.[16] Santapaola was also given life sentences for the murders of Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino.[17][18]

Santapaola allegedly continues to run his clan from inside prison with the help of a string of "regents". On 4 December 2007, his son Vincenzo Santapaola, who allegedly succeeded his father, was arrested.[19] Vincenzo had been in and out of jail since 1992 on various charges including the murder of Antimafia journalist Giuseppe Fava. He now faces charges of trying to reorganise his father's business.[20]

References

[edit]- ^ (in Italian) Catania da primato Archived May 18, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Avvenimenti, February 9, 2007.

- ^ Stille, Excellent Cadavers, p. 74.

- ^ (in Italian) Nitto Santapaola: wanted? Archived 2007-10-07 at the Wayback Machine, I Siciliani, March 1985.

- ^ Stille, Excellent Cadavers, p. 71-73.

- ^ Stille, Excellent Cadavers, p. 177.

- ^ Stille, Excellent Cadavers, p. 232.

- ^ (in Italian) Mancini, il giudice nega l' arresto, Corriere della Sera, October 7, 1993

- ^ (in Italian) Mafia, 'ndrangheta e "l’oro grigio" Archived 2008-04-15 at the Wayback Machine, Calabria Notizie, April 11, 2008

- ^ (in Italian) Article by Riccardo Orioles Archived 2007-08-18 at the Wayback Machine in I Siciliani, April 1993

- ^ (in Italian) I quattro cavalieri dell’apocalisse mafiosa, in I Siciliani, January 1983. The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse are mentioned in the Bible in chapter six of the Book of Revelation. The four horsemen are traditionally named Pestilence, War, Famine, and Death.

- ^ (in Italian) Giuseppe "Pippo" Fava Archived 2007-10-06 at the Wayback Machine by Sebastiano Gulisano, Polizia e Democrazia (2002)

- ^ "I GIUDICI HANNO CREDUTO A BUSCETTA" (in Italian). repubblica.it. 17 December 1987.

- ^ Busting the Mafia: Italy Advances in War on Crime, The New York Times, June 27, 1993

- ^ "As Code of Silence Cracks, Mafia Changes Rules", The New York Times, October 11, 1995

- ^ Women play dual role in pushing Mafia into a brave new world Archived November 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, The Irish Examiner, March 19, 1998

- ^ Mafiosi jailed for life, BBC News, July 19, 1998

- ^ "STRAGE DI CAPACI, 24 ERGASTOLI - La Repubblica.it". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2017.

- ^ "Borsellino bis, sette ergastoli Credibile il pentito Scarantino". repubblica.it. 14 February 1999. Archived from the original on 11 December 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- ^ Raids net 38 as Sicily police aim to stamp out the mafia, The Guardian, December 5, 2007

- ^ Superboss son caught in huge op Archived January 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Italy Magazine, December 5, 2007

Books

[edit]- Arlacchi, Pino; Antonio Calderone (1992). Men of Dishonor. Inside the Sicilian Mafia. An Account of Antonio Calderone. New York: William Morrow & Co.

- Stille, Alexander (1995). Excellent Cadavers. The Mafia and the Death of the First Italian Republic. New York: Vintage. ISBN 0-09-959491-9.

- Caruso, Alfio (2000). Da cosa nasce cosa. Storia della mafia del 1943 a oggi (in Italian). Milan: Longanesi. ISBN 88-304-1620-7.

External links

[edit]- Benedetto Santapaola Biography (in Italian)

- I quattro cavalieri dell’apocalisse mafiosa, by Giuseppe Fava in I Siciliani, January 1983. (in Italian)

- 1938 births

- Fugitives wanted by Italy

- Living people

- People from Catania

- Sicilian Mafia Commission

- Sicilian mafiosi

- Italian people convicted of murdering police officers

- 20th-century Italian criminals

- Italian people convicted of manslaughter

- Italian people convicted of murder

- People convicted of murder by Italy

- Prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment by Italy

- Sicilian mafiosi sentenced to life imprisonment