Ctenotus brooksi

| Ctenotus brooksi | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Family: | Scincidae |

| Genus: | Ctenotus |

| Species: | C. brooksi

|

| Binomial name | |

| Ctenotus brooksi (Loveridge, 1933)

| |

| |

| Ctenotus brooksi distribution - Atlas of Living Australia, Map data © OpenStreetMap, imagery © CartoDB | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

Ctenotus brooksi, also known commonly as Brooks' wedge-snouted ctenotus,[3] the wedgesnout ctenotus,[4] and the sandhill ctenotus,[5] is a species of skink, a lizard in the family Scincidae. The species is endemic to Australia and found in semi-arid regions.[6]

Description

[edit]C. brooksi can reach a total length (including the tail) of 10–12 cm (3.9–4.7 in), noting that lizard measurements are often recorded using the snout-to-vent length (SVL) in recognition that many lizards lose and regrow their tails.[3] C. brooksi has a SVL of 5 cm (2.0 in).[7]

Likely due to the distribution of C. brooksi across isolated populations, there is a large amount of variation in colour and pattern. This variation is significantly more than other Ctenotus species.[8] Its colour varies from fawn, orange, pink, to a reddish brown, changing slightly to a more grey-green on the tail, with a lighter colour underside.[9] It may have a narrow pale-edged black vertical stripe from nape to tail, with or without an additional black stripe or dark flecks on each side of the vertebral stripe.[7] Some individuals may have a white mid-lateral stripe from groin to ear.[4] It supralabials (scales on its upper lip) are usually whitish with faint barring.[8] It has 24 to 28 mid body scale rows, and nasals separated or narrowly contacting.[8]

Like others in the genus Ctenotus, C. brooksi, has smooth scales, ear openings with anterior lobules, well developed limbs, each with five digits.[3] Its lower eyelid is movable, but a transparent palpebral disc is not present in the eyelid.[3] Skinks in the genus Ctenotus are commonly known as "comb-eared skinks" because they have a row of small scales on the anterior edge of the ear.[10]

Identification of individuals within the genus Ctenotus and the broader family Scincidae is also based on the number of scales and how they are distributed on the skink's head as well as lamellae (fine plates) on the underside of the lizard's toes. Detailed examples and diagrams are provided in Reptiles and Amphibians of Australia by Harold Cogger.[7]

Taxonomy and etymology

[edit]This species was first described as a subspecies, Sphenomorphus leae brooksi, by British herpetologist Loveridge in 1933.[8]

It was named after American ornithologist Winthrop Sprague Brooks of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard, who collected reptiles in Western Australia between 1926 and 1927.[11][12]

The taxon was elevated to species status and assigned to the genus Ctenotus by Australian herpetologist Harold Cogger in 1983.[2]

The genus Ctenotus is the largest Australian reptile genus and can be the most difficult to identify.[11] The genus includes 104 species.[3]

Distribution

[edit]The species C. brooksi is endemic to Australia and is found in south-eastern Western Australia, South Australia, Northern Territory, south-western Queensland, north-western New South Wales (NSW) (in the Sturt National Park) and north-western Victoria.[6] It is generally found between latitudes of -20oS and -37oS.[6]

While widespread, populations are thought to be isolated due to areas of stony or clayey terrain between populations.[8]

Ecology and Habitat

[edit]C. brooksi prefers desert sand ridge habitats.[7][4] It prefers areas of loose sand interspersed with vegetation around dune crests.[4] It is likely to be restricted to habitats containing spinifex (Triodia).[13]

C. brooksi is diurnal, surface active, and fast moving, but elusive and rarely observed.[14]

Reproduction

[edit]All species in the genus Ctenotus, including C. brooksi are oviparous, whereby they produce young by laying eggs.[3] They tend to lay their eggs in September and January, which is earlier than many other Ctenotus species. The average clutch size is 2.2.[15]

Diet

[edit]C. brooksi is a generalist as it feeds on a variety of insect prey.[15] It consumes ants, beetles and bugs.[9]

Threats

[edit]One study undertaken in Roxby Downs, in northern South Australia identified feral cats as a key predator of C. brooksi.[16]

While modelling suggests that the range size for C. brooksi is expected to decrease by 2050, it is still classified as having low climate change vulnerability.[15] This is based on a range of variables which include habit specialisation, dietary specialisation, threatened status and clutch size. Notably, other skinks in the genus Ctenotus, such as C. calurus and C. zastictus have been found to be highly vulnerable to climate change.[15]

Uncapped and abandoned opal mining shafts such as those in Coober Pedy have been found to be a hazard for many small vertebrate species, including C. brooksi.[17] Small vertebrates fall down the shafts which can be over 30 metres deep and are permanently open. The number of reptiles caught in shafts per year is estimated to be 10 to 28 million, with a small proportion of these (<1%) being C. brooksi.[17]

Grazing by introduced herbivores that affects the density and structure of spinifex, shrubs and ground cover is believed to degrade C. brooksi habitat, thereby increasing the risk of predation when individuals move between patches of vegetation. Disturbance from stock trampling also degrades C. brooksi habitat by altering soil structure and facilitating weed invasion.[18][5]

The fragmented C. brooksi population results in the species being more vulnerable to stochastic events.[5]

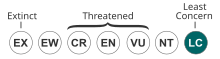

Endangered status

[edit]C. brooksi is categorised as being of 'Least Concern' on the IUCN Red List as it is an abundant species with an overall stable populations.[1] It was however included on the NSW Government vulnerable species listing in 2004 as it was found likely to become endangered in New South Wales unless threatening factors were removed or managed.[5]

Management strategies in NSW

[edit]Due to its vulnerable status in NSW, key management sites will be identified by the NSW Government to implement cost-effective management actions.[19] The identified state-wide conservation actions to be implemented include: footnote here:[19]

Controlling feral goats, feral pigs and rabbits near dense populations

- Control foxes and cats (both domestic & feral) near dense populations

- Encourage livestock management with the aim of maintaining or improving habitat for this species.

- Regular (annual) monitoring of ecological parameters to determine population viability (e.g. breeding success, demography, diet etc).

- Determine the extent of the population and identify key areas for protection.

- Develop recommendations for an 'interim' optimal fire regime.

- Update the Threatened Species Hazard Reduction List with the requirements of this species and ensure personnel undertaking burns are aware of its presence and fire sensitivity.

- Monitor Ctenotus brooksi response to management actions, and identify any new or secondary threats at the site.

- Undertake further research of the ecology, life history and habitat requirements of Ctenotus brooksi.

- Encourage retention of spinifex or porcupine grass (Triodia scariosa) communities, bark, leaf and woody plant litter.

- Focus recovery efforts on two targeted populations per year over initial three years, applying adaptive management strategies to determine and manage threats.

- Include operational guidelines as part of Reserve Fire Management Strategies for Sturt National Park, Mutawintji National Park and Paroo-Darling National Park to protect this species from fire, with patchy burn and a fire frequency of >10 years in Acacia habitat.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Ford, S.; Gaikhorst, G.; How, R.; Cowan, M.; Zichy-Woinarski, J. (2017). "Ctenotus brooksi ". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T109463090A109463093. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T109463090A109463093.en. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ a b Species Ctenotus brooksi at The Reptile Database www.reptile-database.org.

- ^ a b c d e f Wilson, Steve; Swan, Gerry (2017). A Complete Guide to Reptiles of Australia: Fifth Edition. Chatswood, NSW. ISBN 978-1-925546-02-6. OCLC 1003055388.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d "Wedgesnout ctenotus (Ctenotus brooksi) - vulnerable species listing". NSW Environment and Heritage. 9 June 2021. Retrieved 2022-06-11.

- ^ a b c d "Department for Environment and Water - Native animal species list". Department for Environment and Water. Retrieved 2022-06-11.

- ^ a b c Australia, Atlas of Living. "Species: Ctenotus brooksi (Brooks Ctenotus)". bie.ala.org.au. Retrieved 2022-06-12.

- ^ a b c d Cogger, Harold (2019). Reptiles and Amphibians of Australia: Updated Seventh Edition. Collingwood: CSIRO Publishing. 1,080 pp. ISBN 978-1486309696. OCLC 1061116404.

- ^ a b c d e Hutchinson, M.; Adams, M.; Fricker, S. (2006-01-01). "Genetic Variation and Taxonomy of the Ctenotus Brooksi [sic] Species-Complex (Squamata: Scincidae)". Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia. 130 (1): 48–65. doi:10.1080/3721426.2006.10887047. ISSN 0372-1426. S2CID 87854518.

- ^ a b Swan, Gerry (1990). A Field Guide to the Snakes and Lizards of New South Wales. Winmalee, NSW: Three Sisters Productions. ISBN 0-9590203-9-X. OCLC 23830309.

- ^ The Australian Museum. "Ctenotus – Australian Lizards". The Australian Museum. Retrieved 2022-06-12.

- ^ a b Storr, G. M.; Smith, L.A.; Johnstone, R.E. (1999). Lizards of Western Australia. I, Skinks (Rev. ed.). Perth: Western Australian Museum. ISBN 0-7307-2656-8. OCLC 42335524.

- ^ Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. ("Brooks' Ctenotus Ctenotus brooksi ", p. 40).

- ^ Sadlier, R.A.; Pressey, R.L. (1994). "Reptiles and amphibians of particular conservation concern in the Western Division of New South Wales: A preliminary review". Biological Conservation. 69 (1): 41–54. Bibcode:1994BCons..69...41S. doi:10.1016/0006-3207(94)90327-1.

- ^ Swan, Gerry; Shea, Glenn; Sadlier, Ross (2003). A Field Guide to Reptiles of New South Wales. Frenchs Forest, N.S.W.: Reed New Holland. ISBN 1-877069-06-X. OCLC 224012852.

- ^ a b c d Cabrelli, Abigail L.; Hughes, Lesley (2015). "Assessing the vulnerability of Australian skinks to climate change". Climatic Change. 130 (2): 223–233. Bibcode:2015ClCh..130..223C. doi:10.1007/s10584-015-1358-6. ISSN 0165-0009. S2CID 153428168.

- ^ Read, John; Bowen, Zoë (2001). "Population dynamics, diet and aspects of the biology of feral cats and foxes in arid South Australia". Wildlife Research. 28 (2): 195. doi:10.1071/WR99065. ISSN 1035-3712.

- ^ a b Pedler, Reece D. (2010). "The impacts of abandoned mining shafts: Fauna entrapment in opal prospecting shafts at Coober Pedy, South Australia: RESEARCH REPORT". Ecological Management & Restoration. 11 (1): 36–42. doi:10.1111/j.1442-8903.2010.00511.x.

- ^ Read, John L. (2002). "Experimental trial of Australian arid zone reptiles as early warning indicators of overgrazing by cattle: ARID ZONE REPTILES AS INDICATORS OF OVERGRAZING". Austral Ecology. 27 (1): 55–66. doi:10.1046/j.1442-9993.2002.01159.x.

- ^ a b "Wedgesnout Ctenotus (Ctenotus brooksi)". NSW office of Environment & Heritage. Retrieved 2022-06-12.

Further reading

[edit]- Loveridge R (1933). "New Scincid Lizards of the Genera Sphenomorphus, Rhodona, and Lygosoma from Australia". Occasional Papers of the Boston Society of Natural History 8: 95–100. (Sphenomorphus leae brooksi, new subspecies, pp. 95–96).