Gugu hat

Gugu hat (罟罟冠 or 固姑冠 or 顧姑冠 or 故姑冠; pronounced as Guguguan in Chinese) is a tall headdress worn by Mongol noblewomen before and during the Yuan dynasty.[1][2] It is also known as boqta, boghta, botta, boghtagh or boqtaq.[1][3][4] The gugu hat was one of the hallmark headdress of Mongol women in the 13th and 14th century.[1] It was always worn with the formal robe of Mongol women.[1]

The boqta also appeared in the Ilkhanate (1256–1335 AD),[5] in Korea when Mongol princesses married in the Goryeo court,[6] and continued to be used in the Timurid court in the 15th century AD.[7]

Terminology

[edit]Gugu was a Mongolian word for hat; its name was then translated into Chinese based on its pronunciation.[2]

Construction and design

[edit]The Gugu hat was made with wires made of iron and with bamboo strips; they were shaped in the form of a large flask.[2][1] It had the shape of long cylindrical shaft which became more spread out at the top.[1] It could be as tall as one foot high.[6] It could be covered with silk or felt fabric.[1][5] It could be made of red silk or brocade, blue-green brocade, black felt.[1][5] It could also be decorated with precious stones, such as pearls, gold filigrees, large pieces of jewelries in the middle of the hat, and small tuft of quills such as peacock feathers.[1][5][6]

Influences and derivatives

[edit]The gugu hat may have influenced the 15th Century AD conical hats (i.e. hennin) worn by European women.[8] The Korean jokduri might have originated from the gugu hat.[9]

Gallery

[edit]-

Empress Budashiri of Yuan and Khatun of the Mongols.

-

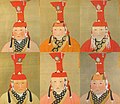

Yuan dynasty empresses wearing gugu hat.

-

Khatun wearing a boqta. Illustration of Rashid-ad-Din's Gami' at-tawarih, 1st quarter of 14th century AD.

-

Women wearing boqta, Illustration of Rashid-ad-Din's Gami' at-tawarih, 1st quarter of 14th century AD.

-

Three women wearing boqta, Illustration of Rashid-ad-Din's Gami' at-tawarih, 1st quarter of 14th century AD.

-

Harem ladies of Ulugh Beg, Timurid court 1425-1450 AD.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i Shea, Eiren L. (2020-02-05). Mongol Court Dress, Identity Formation, and Global Exchange. Routledge. pp. 79–80, 93. doi:10.4324/9780429340659. ISBN 978-0-429-34065-9. S2CID 213078710.

- ^ a b c Yang, Shaorong (2004). Traditional Chinese clothing : costumes, adornments & culture (1 ed.). San Francisco: Long River Press. p. 9. ISBN 1-59265-019-8. OCLC 52775158.

- ^ Shea, Eiren L. (2020). Mongol court dress, identity formation, and global exchange. New York, NY. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-429-34065-9. OCLC 1139920835.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ De Nicola, Bruno (2017). Women in Mongol Iran : the Khātūns, 1206-1335. Edinburgh. pp. 249–250. ISBN 978-1-4744-1548-4. OCLC 981709585.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d Shea, Eiren L. (2020). Mongol court dress, identity formation, and global exchange. New York, NY. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-429-34065-9. OCLC 1139920835.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Robinson, David M. (2009). Empire's twilight : northeast Asia under the Mongols. Cambridge, Mass. p. 102. ISBN 978-1-68417-052-4. OCLC 956712067.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ De Nicola, Bruno (2017). Women in Mongol Iran : the Khātūns, 1206-1335. Edinburgh. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-4744-1548-4. OCLC 981709585.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Shea, Eiren L. (2020). Mongol court dress, identity formation, and global exchange. New York, NY. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-429-34065-9. OCLC 1139920835.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Park, Hyunhee (2021). Soju : a global history. Cambridge, United Kingdom. pp. 124–125. ISBN 978-1-108-89577-4. OCLC 1198087560.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)