Lord Kitchener Wants You

The London Opinion published poster: "Britons: Lord Kitchener Wants You. Join Your Country's Army! God save the King." Modern reproduction from IWM | |

| Language | English |

|---|---|

| Media | Watercolour; print |

| Release date(s) | 1914 |

| Country | United Kingdom |

Lord Kitchener Wants You is a 1914 advertisement by Alfred Leete which was developed into a recruitment poster. It depicted Lord Kitchener, the British Secretary of State for War, above the words "WANTS YOU". Kitchener, wearing the cap of a British field marshal, stares and points at the viewer calling them to enlist in the British Army against the Central Powers. The image is considered one of the most iconic and enduring images of World War I. A hugely influential image and slogan, it has inspired imitations in other countries.

Development

[edit]British policy for a century had been that recruitment to the British armed forces was strictly volunteer. Before the outbreak of the First World War, recruiting posters had not been used in Britain on a regular basis since the Napoleonic Wars. UK government advertisements for contract work were handled by His Majesty's Stationery Office, who passed this task on to the publishers R. F. White & Sons in order to avoid paying the government rate to newspaper publishers. As war loomed in late 1913, the number of advertising contracts expanded to include other firms. J. E. B. Seely, then the Secretary of State for War, awarded Hedley Le Bas, Eric Field, and their Caxton Advertising Agency a contract to advertise for recruits in the major UK newspapers. Eric Field designed a prototype full-page advertisement with the coat of arms of King George V and the phrase "Your King and Country Need You." Britain declared war on the German Empire on 4 August 1914 and the first run of the full-page advert ran the next day in those newspapers owned by Lord Northcliffe.[1]

The Prime Minister H. H. Asquith appointed Kitchener as Secretary of State for War in August 1914.[2] Kitchener was the first currently serving soldier to hold the post and was given the task of recruiting a large army to fight Germany. Unlike some of his contemporaries who expected a short conflict, Kitchener foresaw a much longer war requiring hundreds of thousands of enlistees.[3][4] According to Gary S. Messinger, Kitchener reacted well to Field's advertisement, although he insisted "that the ads should all end with 'God Save the King' and that they should not be changed from the original text, except to say 'Lord Kitchener needs YOU.'" In the following months, Le Bas formed an advisory committee of ad men to develop further newspaper recruiting advertisements, most of which ran vertically 11 in (28 cm), two columns wide.[5]

Alfred Leete, one of Caxton's illustrators, designed the now-famous image of Kitchener as the cover illustration for the 5 September 1914 issue of London Opinion, a popular weekly magazine, taking cues from Field's earlier recruiting advertisement.[6][7] At the time, the magazine, which sold for one penny, had a circulation of around 300,000.[8]

In response to requests for reproductions, the magazine offered postcard-sized copies for sale – at 100 for 1s 4 d "post free". It advertised these alongside other post cards from cartoons published in the London Opinion [9] The Parliamentary Recruiting Committee obtained permission to use the design in poster form.[10] A similar poster used the words "YOUR COUNTRY NEEDS YOU".[11]

In September a poster printed by Victoria House and credited to the London Opinion carried the image of Kitchener below "Britons" and above "Wants You" "Join your Country's Army! God, Save The King". In November David Allen and Sons printed the same Kitchener image with "your country needs you" on a recruitment poster below the allied flags alongside details of rates of pay and exhortations to join. Although David Allen were printers for the Parliamentary Recruiting Committee it was not an official publication, lacking design number and the PRC endorsement.[12]

Kitchener, a "figure of absolute will and power, an emblem of British masculinity",[13] was a natural subject for Leete's artwork as his name was directly attached to the recruiting efforts and the newly-forming Kitchener's Army.[14] Le Bas of Caxton Advertising (for whom Leete worked) chose Kitchener for the advertisement because Kitchener was "the only soldier with a great war name, won in the field, within the memory of the thousands of men the country wanted."[15] Kitchener made his name in the Sudan Campaign, avenging the death of General Gordon with brutality and efficiency.[16] He became a hero of "New Imperialism" alongside other widely regarded figures in Britain like Field Marshal Wolseley and Field Marshal Roberts.[17] [18] Kitchener's appearance including his bushy moustache and the collar of his uniform was reminiscent of romanticised Victorian era styles.[19] Kitchener, 6 ft 2 in (188 cm) tall and powerfully built, was for many the personification of the military ethos so popular in the present Edwardian era.[20] After the scorched earth tactics and hard-fought victory of the Second Boer War, Kitchener represented a return to the military victories of the colonial era.[21] The fact that Kitchener's name was not used in the poster demonstrates how easily he was visually recognised.[22] David Lubin opines that the image may be one of the earliest successful celebrity endorsements as the commercial practice expanded greatly in the 1920s.[23] Keith Surridge posits that Kitchener's features evoked the harsh, feared militarism of the Germans, which boded well for British fortunes in the war.[24] Kitchener did not see the end of the war; he died when the cruiser HMS Hampshire carrying him and a delegation to Russia struck a German mine and sank in 1916.[25]

Impact

[edit]He is not a great man, he is a great poster.[26]

Leete's drawing of Kitchener was the most famous image used in the British Army recruitment campaign of World War I.[2][10] It continues to be considered a masterful piece of wartime propaganda as well as an enduring and iconic image of the war.[27][28][29][30][31][32]

Recruitment posters in general have often been seen as a driving force helping to bring more than a million men into the Army.[33] September 1914, coincident with publication of Leete's image, saw the highest number of volunteers enlisted.[10] The Times recorded the scene in London on 3 January 1915; "Posters appealing to recruits are to be seen on every hoarding, in most windows, in omnibuses, tramcars and commercial vans. The great base of Nelson's Column is covered with them. Their number and variety are remarkable. Everywhere Lord Kitchener sternly points a monstrously big finger, exclaiming 'I Want You'".[10][34] One contemporaneous publication decried the use of advertising methods to enlist soldiers: "the cold, basilisk eye of a gaudily-lithographed Kitchener rivets itself upon the possible recruit and the outstretched finger of the British Minister of War is levelled at him like some revolver, with the words, 'I want you.' The idea is stolen from the advertisement of a 5c. American cigar."[35] Although it became one of the most famous posters in history,[10] its widespread circulation did not halt the decline in recruiting.[10]

The use of Kitchener's image for recruiting posters was so widespread that Lady Asquith referred to the field marshal simply as "the Poster".[23]

The placement of the Kitchener posters including Alfred Leete's design has been examined and questioned following an Imperial War Museum publication in 1997. The museum suggested that the poster itself was a "non event" and was made popular by postwar advertising by the war museum, perhaps conflating Leete's design with the so-called "30-word" poster, an official product from the Parliamentary Recruitment Committee.[15] The 30-word design was the most popular recruitment poster at the time, having been printed ten times more than Leete's image.[8][36] Leete's image has been praised for being more arresting, while his accompanying text is also far less verbose. The official wording, taken from a Kitchener speech, may seem more fitting for a character in a Henry James novel.[23] The 30-word recruiting poster was developed as Britons' collective hopes of the war being over by Christmas were dashed in January 1915 and volunteer enlistments fell.[37] A 2013 book researched by James Taylor counters the popular belief that the Leete design was an influential recruitment tool during the war. He claims the original artwork was acquired by the Imperial War Museum in 1917 and catalogued as a poster in error.[8] Though the image of Kitchener (Britain's most popular soldier) inspired several other poster designs, Taylor says he can find no evidence that the poster was as popular or influential as later stated having examined many contemporary photographs, although a photograph from 15 December 1914 taken at the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway station in Liverpool clearly depicts Leete's depiction among other recruiting posters.[8][38]

The effectiveness of the image upon the viewer is attributed to what E. B. Goldstein has called the "differential rotation effect". Because of this effect, Kitchener's eyes and his foreshortened arm and hand appear to follow the viewer regardless of the viewer's orientation to the artwork.[39][40][41] Historian Carlo Ginzburg compared Leete's image of Kitchener to similar images of Christ and Alexander the Great as depicting the viewer's contact with a powerful figure.[42] Pearl James commented on Ginzburg's analysis agreeing that the strength of the connotation lies with a clever use of discursive psychology and that art historical methods better illuminate why this image has such resonance.[43] The capitalised word "YOU" grabs the reader, bringing them directly to Kitchener's message.[23] The textual focus on "you" engages the reader about their own participation in the war.[44] Nicholas Hiley differs in that Leete's portrayal of Kitchener is less about immediate recruiting statistics but the myth that has grown around the image, including ironic parodies.[15][45] Leete's Kitchener poster caught the attention of a then eleven-year-old George Orwell, who may have used it as the basis for his description of the "Big Brother" posters in his novel 1984.[23] It remains recognised and parodied in popular culture.[46]

In 1997 the British Army created a recruiting advertisement re-using Leete's image but substituting for Kitchener's face that of a British Army non-commissioned officer of African descent.[47] Leete's image of Kitchener is featured on a 2014 £2 coin produced by sculptor John Bergdahl for the Royal Mint. The coin was the first of a five-year series to commemorate the centennial of the war.[48] Use of Leete's image of Kitchener has been criticised by some for its pro-war connotation in light of the human losses of the First World War and the violence of Kitchener's campaign in Sudan.[49] In July 2014, one of only four original posters known to exist went to auction for more than £10,000. The other three originals exist on display in State Library Victoria, the Museum of Brands, Packaging and Advertising, and the Imperial War Museum.[50][51] Leete's design was also used for a corn maze in the Skylark Garden Centre in Wimblington to mark the centenary of World War I.[52]

Original copies of the poster are rare compared to official PRC posters that were produced in up to a hundred thousand copies. The IWM, established in 1917, did not receive a copy for its collection until the 1950s. Leete's original artwork for the magazine cover version was exhibited alongside war posters in 1919 and donated to the IWM. In 1968 reproductions were printed by the Curwen Press for HMSO and these may have contributed to its later popularity.[53]

Imitations

[edit]The image of Lord Kitchener with his hand pointing directly at the viewer has inspired numerous imitations, mostly for military recruitment:

-

British World War I recruiting poster featuring the national personification, John Bull, c. 1915. "Who's absent? Is it you?"

-

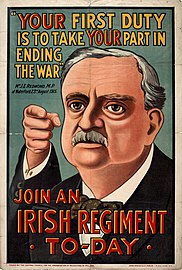

John Redmond. Join an Irish Regiment, 1915

-

United States, 1917. J. M. Flagg's Uncle Sam recruited soldiers for World War I and thereafter. "I Want YOU for U.S. Army"[54]

-

United States, World War I. Daughter of Zion (in Yiddish): "Your Old New Land must have you! Join the Jewish regiment"

-

Reichswehr recruitment poster by Julius Ussy Engelhard, 1919. "You too should join the Reichswehr"

-

Russian White Army recruitment poster, 1919. "Why aren't you in the army?"

-

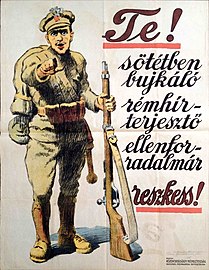

“You! rumour-mongering counter-revolutionary lurking in the dark, tremble!” Hungary, 1919, the time of Hungarian Soviet Republic

-

Russian Red Army recruitment poster, 1920. "Did you volunteer [to Red Army]?"

-

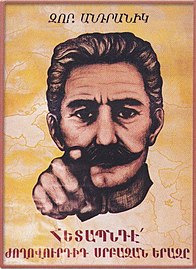

Armenia, Gen. Andranik (1865-1927) poster, "Chase the holy dream of your people"

-

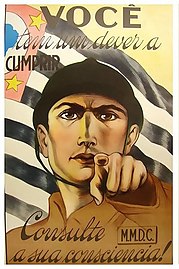

Brazilian Constitutionalist Revolution recruitment poster, 1932. "You have a duty to fulfill. Consult your conscience!"

-

Spanish Civil War Anarchist poster, 1936

-

Soviet World War II poster, 1941. "How did you help the Front?"

-

Jože Beranek - Slovene Home Guard 1944

-

Boccasile: recruitment poster for Republic of Salò navy

-

World War I Canadian bond sale poster, c. 1917-1918, derivative of Flagg's Uncle Sam poster, itself derivative of Lord Kitchener[55]

-

Poster for Japanese Communist Party magazine Zenei (Vanguard), 1928. "Look! We are the only combative proletarian arts magazine."[56]

-

United States 1985 Smokey Bear poster. The "Only You" refers to the character's slogan, "Only You Can Prevent Forest Fires"

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Messinger 1992, pp. 214–216.

- ^ a b "Historic Figures – Lord Horatio Kitchener (1850–1916)". BBC. Archived from the original on 2 September 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2011

- ^ Jones, Nigel (16 December 2013). Peace And War: Britain In 1914. Head of Zeus. pp. 222–223. ISBN 978-1-78185-253-8. Archived from the original on 28 March 2017. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ Welch & Fox 2012, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Messinger 1992, pp. 216–217.

- ^ Stride, Helena (12 May 2008). "Call to arms". TES. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ Pollock, John (19 September 2013). Kitchener: The Road to Omdurman and Saviour of the Nation. Constable & Robinson Ltd. ISBN 9781472113344.

- ^ a b c d Copping, Jasper (2 August 2013). "'Your Country Needs You' – The myth about the First World War poster that 'never existed'". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 4 December 2013. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ^ Taylor 2013, p. x.

- ^ a b c d e f Simkins, Peter (1988). Kitchener's army: the raising of the new armies, 1914–16. Manchester University Press. pp. 122–123. ISBN 9780719026386.

- ^ Lord Kitchener "Your country needs you!". Sterling Times. Retrieved 31 March 2011 Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Taylor 2013, p. y.

- ^ Tynan 2013, p. 35.

- ^ Tynan 2013, pp. 46–47.

- ^ a b c Hiley, Nicholas (1997). "Kitchener wants YOU and Daddy what did YOU do in the great war?: The Myth of British Recruiting Posters". Imperial War Museum Review. 11: 40–58.

- ^ The Mahdist forces were defeated at the Battle of Omdurman 13 years after Gordon died at Khartoum

- ^ Welch & Fox 2012, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Surridge 2001, pp. 298, 305.

- ^ Tynan 2013, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Surridge 2001, pp. 307–308.

- ^ Welch & Fox 2012, p. 52.

- ^ Surridge 2001, p. 311.

- ^ a b c d e Lubin, David M. (September 2011). "Losing Sight: War, Authority, and Blindness in British and American Visual Cultures, 1914–22". Art History. 34 (4): 796–817. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8365.2010.00847.x.

- ^ Surridge 2001, p. 309.

- ^ Surridge 2001, pp. 312–313.

- ^ Gosling, Lucinda (2008). Brushes and Bayonets: Cartoons, Sketches and Paintings of World War I. Osprey Publishing. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-84603-095-6.

- ^ "British First World War Recruiting Posters". McMaster University. Archived from the original on 4 March 2014. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ "Propaganda 1914–18". The National Archives. Archived from the original on 4 March 2014. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ Taylor, Philip M. (1999). British Propaganda in the 20th Century: Selling Democracy. Edinburgh University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-7486-1040-2. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ Sooke, Alastair (3 July 2013). "Can propaganda be great art?". BBC. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ Hardie, Martin; Sabin, Arthur Knowles (1920). War posters issued by belligerent and neutral nations 1914–1919. London: A & C Black. p. 9. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- ^ Hughes-Wilson, John; Steel, Nigel (2014). A History Of The First World War In 100 Objects: In Association With The Imperial War Museum. Octopus Books. ISBN 978-1-84403-760-5. Archived from the original on 17 May 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ^ "British History in depth: The Pals Battalions in World War One". BBC. Archived from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019. Retrieved 31 March 2011

- ^ Taylor identifies this as Michael MacDonagh writing in 1935 and notes the "I want you" is not the words of the poster but of Montgomery Flagg's Uncle Sam

- ^ Orchelle, R. L. (15 May 1915). "The Soul of England". The Vital Issue. 2 (20): 4. Archived from the original on 19 May 2015. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- ^ Eley, Adam (4 August 2014). "Kitchener: The most famous pointing finger". BBC News. Archived from the original on 24 December 2017. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ White, Bonnie J. (2009). "Volunteerism and Early Recruitment Efforts in Devonshire, August 1914 – December 1915". The Historical Journal. 52 (3): 641–666. doi:10.1017/S0018246X09990069. S2CID 162930663.

- ^ "First World War posters, 1914". National Railway Museum. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ Cutting, James E. (1988). "Affine Distortions of Pictorial Space: Some Predictions for Goldstein (1987) That La Gournerie (1859) Might Have Made". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 14 (2): 305–311. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.211.6850. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.14.2.305. PMID 2967882.

- ^ Koenderink, Jan J.; van Doorn, Andrea J.; Kappers, Astrid M. L.; Todd, James T. (2004). "Pointing out of the picture". Perception. 33 (5): 513–530. doi:10.1068/p3454. PMID 15250658. S2CID 21106776. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ Busey, Thomas A.; Brady, Nuala P.; Cutting, James E. (1990). "Compensation is unnecessary for the perception of faces in slanted pictures" (PDF). Perception & Psychophysics. 48 (1): 2. doi:10.3758/bf03205006. PMID 2377436. S2CID 18049077. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 June 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ Ginzburg, Carlo (2001). "'Your Country Needs You': A Case Study in Political Iconography" (PDF). History Workshop Journal (52): 1–22. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 December 2014. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ James 2009, p. 21.

- ^ Chambers, R. (1983). "Art and Propaganda in an Age of War: The Role of Posters" (pdf). South African Journal of Military Studies. 13 (4). Archived from the original on 4 March 2014. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

- ^ James 2009, p. 18.

- ^ "Lord Kitchener "Your country needs you!"". Sterling Times. Archived from the original on 26 March 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- ^ Surridge 2001, p. 298.

- ^ "The 100th Anniversary of the FWW – Outbreak UK £2 Brilliant Uncirculated Coin". Royal Mint. 20 February 2014. Archived from the original on 24 August 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ "Calls for 'offensive' Kitchener WWI centenary coin to be scrapped". The Herald. 14 January 2014. Archived from the original on 12 February 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ Sim, David (8 July 2014). "Lord Kitchener Wants You: Rare First World War Posters Go On Sale". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 8 July 2014. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ^ "About Us". Robert Opie Collection. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 9 July 2014.

- ^ "Lord Kitchener WW1 poster created in Cambridgeshire maize maze". BBC News. 18 July 2014. Archived from the original on 8 January 2019. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ Taylor, Chapter One

- ^ Capozzola, Christopher (2008). Uncle Sam Wants You : World War I and the Making of the Modern American Citizen. Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-19-533549-1.

- ^ "First World War Propaganda Poster: Buy Your Victory Bonds". Canadian Wartime Propaganda. Canadian War Museum. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ^ Gerteis, Christopher. "MIT Visualizing Cultures". visualizingcultures.mit.edu. Archived from the original on 17 April 2023. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- James, Pearl (2009). Picture This: World War I Posters and Visual Culture. University of Nebraska. ISBN 978-0-8032-2610-4.

- Messinger, Gary S. (1992). British Propaganda and the State in the First World War. Manchester University Press. pp. 214–216. ISBN 978-0-7190-3014-7.

- Surridge, Keith (2001). "More than a great poster: Lord Kitchener and the image of the military hero". Historical Research. 74 (185): 298–313. doi:10.1111/1468-2281.00129.

- Taylor, James (2013), Your Country Needs You: the Secret History of the Propaganda Poster, Glasgow: Saraband, ISBN 9781887354974

- Tynan, Jane (2013). British Army Uniform and the First World War: Men in Khaki. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-31831-2.

- Welch, David; Fox, Jo, eds. (2012). Justifying War: Propaganda, Politics and the Modern Age. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-24627-0. Retrieved 4 March 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- Thatcher, Martyn; Quinn, Anthony (1 October 2013). The Amazing Story of the Kitchener Poster. Funfly Design. ISBN 978-0-9569094-2-8.

External links

[edit] Media related to Lord Kitchener Wants You at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Lord Kitchener Wants You at Wikimedia Commons

![United States, 1917. J. M. Flagg's Uncle Sam recruited soldiers for World War I and thereafter. "I Want YOU for U.S. Army"[54]](/media/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/59/J._M._Flagg%2C_I_Want_You_for_U.S._Army_poster_%281917%29.jpg/203px-J._M._Flagg%2C_I_Want_You_for_U.S._Army_poster_%281917%29.jpg)

![Russian Red Army recruitment poster, 1920. "Did you volunteer [to Red Army]?"](/media/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e6/%D0%9C%D0%BE%D0%BE%D1%80._%D0%A2%D1%8B_%D0%B7%D0%B0%D0%BF%D0%B8%D1%81%D0%B0%D0%BB%D1%81%D1%8F_%D0%B4%D0%BE%D0%B1%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%BE%D0%BB%D1%8C%D1%86%D0%B5%D0%BC.jpg/180px-%D0%9C%D0%BE%D0%BE%D1%80._%D0%A2%D1%8B_%D0%B7%D0%B0%D0%BF%D0%B8%D1%81%D0%B0%D0%BB%D1%81%D1%8F_%D0%B4%D0%BE%D0%B1%D1%80%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%BE%D0%BB%D1%8C%D1%86%D0%B5%D0%BC.jpg)

![World War I Canadian bond sale poster, c. 1917-1918, derivative of Flagg's Uncle Sam poster, itself derivative of Lord Kitchener[55]](/media/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a9/Buy_Your_Victory_Bonds._Color_poster._Issued_by_Victory_Bond_Committee%2C_Ottawa%2C_Canada.%2C_ca._1917_-_NARA_-_516338.jpg/196px-Buy_Your_Victory_Bonds._Color_poster._Issued_by_Victory_Bond_Committee%2C_Ottawa%2C_Canada.%2C_ca._1917_-_NARA_-_516338.jpg)

![Poster for Japanese Communist Party magazine Zenei (Vanguard), 1928. "Look! We are the only combative proletarian arts magazine."[56]](/media/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9e/Listen%21_Workers_of_All_Nations%21_1931.jpg/193px-Listen%21_Workers_of_All_Nations%21_1931.jpg)