Portal:Minerals

Portal maintenance status: (May 2019)

|

The Minerals Portal

In geology and mineralogy, a mineral or mineral species is, broadly speaking, a solid substance with a fairly well-defined chemical composition and a specific crystal structure that occurs naturally in pure form.

The geological definition of mineral normally excludes compounds that occur only in living organisms. However, some minerals are often biogenic (such as calcite) or organic compounds in the sense of chemistry (such as mellite). Moreover, living organisms often synthesize inorganic minerals (such as hydroxylapatite) that also occur in rocks.

The concept of mineral is distinct from rock, which is any bulk solid geologic material that is relatively homogeneous at a large enough scale. A rock may consist of one type of mineral or may be an aggregate of two or more different types of minerals, spacially segregated into distinct phases.

Some natural solid substances without a definite crystalline structure, such as opal or obsidian, are more properly called mineraloids. If a chemical compound occurs naturally with different crystal structures, each structure is considered a different mineral species. Thus, for example, quartz and stishovite are two different minerals consisting of the same compound, silicon dioxide. (Full article...)

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the processes of mineral origin and formation, classification of minerals, their geographical distribution, as well as their utilization. (Full article...)

Selected articles

-

Image 1

Opal is a hydrated amorphous form of silica (SiO2·nH2O); its water content may range from 3% to 21% by weight, but is usually between 6% and 10%. Due to the amorphous (chemical)physical structure, it is classified as a mineraloid, unlike crystalline forms of silica, which are considered minerals. It is deposited at a relatively low temperature and may occur in the fissures of almost any kind of rock, being most commonly found with limonite, sandstone, rhyolite, marl, and basalt.

The name opal is believed to be derived from the Sanskrit word upala (उपल), which means 'jewel', and later the Greek derivative opállios (ὀπάλλιος).

There are two broad classes of opal: precious and common. Precious opal displays play-of-color (iridescence); common opal does not. Play-of-color is defined as "a pseudo chromatic optical effect resulting in flashes of colored light from certain minerals, as they are turned in white light." The internal structure of precious opal causes it to diffract light, resulting in play-of-color. Depending on the conditions in which it formed, opal may be transparent, translucent, or opaque, and the background color may be white, black, or nearly any color of the visual spectrum. Black opal is considered the rarest, while white, gray, and green opals are the most common. (Full article...) -

Image 2

Rutile is an oxide mineral composed of titanium dioxide (TiO2), the most common natural form of TiO2. Rarer polymorphs of TiO2 are known, including anatase, akaogiite, and brookite.

Rutile has one of the highest refractive indices at visible wavelengths of any known crystal and also exhibits a particularly large birefringence and high dispersion. Owing to these properties, it is useful for the manufacture of certain optical elements, especially polarization optics, for longer visible and infrared wavelengths up to about 4.5 micrometres. Natural rutile may contain up to 10% iron and significant amounts of niobium and tantalum.

Rutile derives its name from the Latin rutilus ('red'), in reference to the deep red color observed in some specimens when viewed by transmitted light. Rutile was first described in 1803 by Abraham Gottlob Werner using specimens obtained in Horcajuelo de la Sierra, Madrid (Spain), which is consequently the type locality. (Full article...) -

Image 3

Borax (also referred to as sodium borate, tincal (/ˈtɪŋkəl/) and tincar (/ˈtɪŋkər/)) is a salt (ionic compound), a hydrated or anhydrous borate of sodium, with the chemical formula Na2H20B4O17.

It is a colorless crystalline solid that dissolves in water to make a basic solution.

It is commonly available in powder or granular form and has many industrial and household uses, including as a pesticide, as a metal soldering flux, as a component of glass, enamel, and pottery glazes, for tanning of skins and hides, for artificial aging of wood, as a preservative against wood fungus, and as a pharmaceutic alkalizer. In chemical laboratories, it is used as a buffering agent.

The terms tincal and tincar refer to native borax, historically mined from dry lake beds in various parts of Asia. (Full article...) -

Image 4

Cinnabar (/ˈsɪnəˌbɑːr/; from Ancient Greek κιννάβαρι (kinnábari)), or cinnabarite (/ˌsɪnəˈbɑːraɪt/), also known as mercurblende is the bright scarlet to brick-red form of mercury(II) sulfide (HgS). It is the most common source ore for refining elemental mercury and is the historic source for the brilliant red or scarlet pigment termed vermilion and associated red mercury pigments.

Cinnabar generally occurs as a vein-filling mineral associated with volcanic activity and alkaline hot springs. The mineral resembles quartz in symmetry and it exhibits birefringence. Cinnabar has a mean refractive index near 3.2, a hardness between 2.0 and 2.5, and a specific gravity of approximately 8.1. The color and properties derive from a structure that is a hexagonal crystalline lattice belonging to the trigonal crystal system, crystals that sometimes exhibit twinning.

Cinnabar has been used for its color since antiquity in the Near East, including as a rouge-type cosmetic, in the New World since the Olmec culture, and in China since as early as the Yangshao culture, where it was used in coloring stoneware. In Roman times, cinnabar was highly valued as paint for walls, especially interiors, since it darkened when used outdoors due to exposure to sunlight.

Associated modern precautions for the use and handling of cinnabar arise from the toxicity of the mercury component, which was recognized as early as ancient Rome. (Full article...) -

Image 5Deep green isolated fluorite crystal resembling a truncated octahedron, set upon a micaceous matrix, from Erongo Mountain, Erongo Region, Namibia (overall size: 50 mm × 27 mm, crystal size: 19 mm wide, 30 g)

Fluorite (also called fluorspar) is the mineral form of calcium fluoride, CaF2. It belongs to the halide minerals. It crystallizes in isometric cubic habit, although octahedral and more complex isometric forms are not uncommon.

The Mohs scale of mineral hardness, based on scratch hardness comparison, defines value 4 as fluorite.

Pure fluorite is colourless and transparent, both in visible and ultraviolet light, but impurities usually make it a colorful mineral and the stone has ornamental and lapidary uses. Industrially, fluorite is used as a flux for smelting, and in the production of certain glasses and enamels. The purest grades of fluorite are a source of fluoride for hydrofluoric acid manufacture, which is the intermediate source of most fluorine-containing fine chemicals. Optically clear transparent fluorite has anomalous partial dispersion, that is, its refractive index varies with the wavelength of light in a manner that differs from that of commonly used glasses, so fluorite is useful in making apochromatic lenses, and particularly valuable in photographic optics. Fluorite optics are also usable in the far-ultraviolet and mid-infrared ranges, where conventional glasses are too opaque for use. Fluorite also has low dispersion, and a high refractive index for its density. (Full article...) -

Image 6

Turquoise is an opaque, blue-to-green mineral that is a hydrous phosphate of copper and aluminium, with the chemical formula CuAl6(PO4)4(OH)8·4H2O. It is rare and valuable in finer grades and has been prized as a gemstone for millennia due to its hue.

Like most other opaque gems, turquoise has been devalued by the introduction of treatments, imitations, and synthetics into the market. The robin egg blue or sky blue color of the Persian turquoise mined near the modern city of Nishapur, Iran, has been used as a guiding reference for evaluating turquoise quality. (Full article...) -

Image 7

Apatite is a group of phosphate minerals, usually hydroxyapatite, fluorapatite and chlorapatite, with high concentrations of OH−, F− and Cl− ion, respectively, in the crystal. The formula of the admixture of the three most common endmembers is written as Ca10(PO4)6(OH,F,Cl)2, and the crystal unit cell formulae of the individual minerals are written as Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2, Ca10(PO4)6F2 and Ca10(PO4)6Cl2.

The mineral was named apatite by the German geologist Abraham Gottlob Werner in 1786, although the specific mineral he had described was reclassified as fluorapatite in 1860 by the German mineralogist Karl Friedrich August Rammelsberg. Apatite is often mistaken for other minerals. This tendency is reflected in the mineral's name, which is derived from the Greek word ἀπατάω (apatáō), which means to deceive. (Full article...) -

Image 8Dolomite (white) on talc

Dolomite (/ˈdɒl.əˌmaɪt, ˈdoʊ.lə-/) is an anhydrous carbonate mineral composed of calcium magnesium carbonate, ideally CaMg(CO3)2. The term is also used for a sedimentary carbonate rock composed mostly of the mineral dolomite (see Dolomite (rock)). An alternative name sometimes used for the dolomitic rock type is dolostone. (Full article...) -

Image 9

The mineral pyrite (/ˈpaɪraɪt/ PY-ryte), or iron pyrite, also known as fool's gold, is an iron sulfide with the chemical formula FeS2 (iron (II) disulfide). Pyrite is the most abundant sulfide mineral.

Pyrite's metallic luster and pale brass-yellow hue give it a superficial resemblance to gold, hence the well-known nickname of fool's gold. The color has also led to the nicknames brass, brazzle, and brazil, primarily used to refer to pyrite found in coal.

The name pyrite is derived from the Greek πυρίτης λίθος (pyritēs lithos), 'stone or mineral which strikes fire', in turn from πῦρ (pŷr), 'fire'. In ancient Roman times, this name was applied to several types of stone that would create sparks when struck against steel; Pliny the Elder described one of them as being brassy, almost certainly a reference to what is now called pyrite.

By Georgius Agricola's time, c. 1550, the term had become a generic term for all of the sulfide minerals. (Full article...) -

Image 10

Zeolite exhibited in the Estonian Museum of Natural History

Zeolite is a family of several microporous, crystalline aluminosilicate materials commonly used as commercial adsorbents and catalysts. They mainly consist of silicon, aluminium, oxygen, and have the general formula Mn+

1/n(AlO

2)−

(SiO

2)

x・yH

2O where Mn+

1/n is either a metal ion or H+.

The term was originally coined in 1756 by Swedish mineralogist Axel Fredrik Cronstedt, who observed that rapidly heating a material, believed to have been stilbite, produced large amounts of steam from water that had been adsorbed by the material. Based on this, he called the material zeolite, from the Greek ζέω (zéō), meaning "to boil" and λίθος (líthos), meaning "stone".

Zeolites occur naturally, but are also produced industrially on a large scale. As of December 2018[update], 253 unique zeolite frameworks have been identified, and over 40 naturally occurring zeolite frameworks are known. Every new zeolite structure that is obtained is examined by the International Zeolite Association Structure Commission (IZA-SC) and receives a three-letter designation. (Full article...) -

Image 11

Mineralogy applies principles of chemistry, geology, physics and materials science to the study of minerals

Mineralogy is a subject of geology specializing in the scientific study of the chemistry, crystal structure, and physical (including optical) properties of minerals and mineralized artifacts. Specific studies within mineralogy include the processes of mineral origin and formation, classification of minerals, their geographical distribution, as well as their utilization. (Full article...) -

Image 12

Magnetite is a mineral and one of the main iron ores, with the chemical formula Fe2+Fe3+2O4. It is one of the oxides of iron, and is ferrimagnetic; it is attracted to a magnet and can be magnetized to become a permanent magnet itself. With the exception of extremely rare native iron deposits, it is the most magnetic of all the naturally occurring minerals on Earth. Naturally magnetized pieces of magnetite, called lodestone, will attract small pieces of iron, which is how ancient peoples first discovered the property of magnetism.

Magnetite is black or brownish-black with a metallic luster, has a Mohs hardness of 5–6 and leaves a black streak. Small grains of magnetite are very common in igneous and metamorphic rocks.

The chemical IUPAC name is iron(II,III) oxide and the common chemical name is ferrous-ferric oxide. (Full article...) -

Image 13

A rock containing three crystals of pyrite (FeS2). The crystal structure of pyrite is primitive cubic, and this is reflected in the cubic symmetry of its natural crystal facets.

In crystallography, the cubic (or isometric) crystal system is a crystal system where the unit cell is in the shape of a cube. This is one of the most common and simplest shapes found in crystals and minerals.

There are three main varieties of these crystals:- Primitive cubic (abbreviated cP and alternatively called simple cubic)

- Body-centered cubic (abbreviated cI or bcc)

- Face-centered cubic (abbreviated cF or fcc)

Note: the term fcc is often used in synonym for the cubic close-packed or ccp structure occurring in metals. However, fcc stands for a face-centered-cubic Bravais lattice, which is not necessarily close-packed when a motif is set onto the lattice points. E.g. the diamond and the zincblende lattices are fcc but not close-packed.

Each is subdivided into other variants listed below. Although the unit cells in these crystals are conventionally taken to be cubes, the primitive unit cells often are not. (Full article...) -

Image 14

Micas (/ˈmaɪkəz/ MY-kəz) are a group of silicate minerals whose outstanding physical characteristic is that individual mica crystals can easily be split into fragile elastic plates. This characteristic is described as perfect basal cleavage. Mica is common in igneous and metamorphic rock and is occasionally found as small flakes in sedimentary rock. It is particularly prominent in many granites, pegmatites, and schists, and "books" (large individual crystals) of mica several feet across have been found in some pegmatites.

Micas are used in products such as drywalls, paints, and fillers, especially in parts for automobiles, roofing, and in electronics. The mineral is used in cosmetics and food to add "shimmer" or "frost". (Full article...) -

Image 15A sample of andesite (dark groundmass) with amygdaloidal vesicles filled with zeolite. Diameter of view is 8 cm.

Andesite (/ˈændəzaɪt/) is a volcanic rock of intermediate composition. In a general sense, it is the intermediate type between silica-poor basalt and silica-rich rhyolite. It is fine-grained (aphanitic) to porphyritic in texture, and is composed predominantly of sodium-rich plagioclase plus pyroxene or hornblende.

Andesite is the extrusive equivalent of plutonic diorite. Characteristic of subduction zones, andesite represents the dominant rock type in island arcs. The average composition of the continental crust is andesitic. Along with basalts, andesites are a component of the Martian crust.

The name andesite is derived from the Andes mountain range, where this rock type is found in abundance. It was first applied by Christian Leopold von Buch in 1826. (Full article...) -

Image 16

The diamond crystal structure belongs to the face-centered cubic lattice, with a repeated two-atom pattern.

In crystallography, a crystal system is a set of point groups (a group of geometric symmetries with at least one fixed point). A lattice system is a set of Bravais lattices. Space groups are classified into crystal systems according to their point groups, and into lattice systems according to their Bravais lattices. Crystal systems that have space groups assigned to a common lattice system are combined into a crystal family.

The seven crystal systems are triclinic, monoclinic, orthorhombic, tetragonal, trigonal, hexagonal, and cubic. Informally, two crystals are in the same crystal system if they have similar symmetries (though there are many exceptions). (Full article...) -

Image 17

Green fluorite with prominent cleavage

Cleavage, in mineralogy and materials science, is the tendency of crystalline materials to split along definite crystallographic structural planes. These planes of relative weakness are a result of the regular locations of atoms and ions in the crystal, which create smooth repeating surfaces that are visible both in the microscope and to the naked eye. If bonds in certain directions are weaker than others, the crystal will tend to split along the weakly bonded planes. These flat breaks are termed "cleavage". The classic example of cleavage is mica, which cleaves in a single direction along the basal pinacoid, making the layers seem like pages in a book. In fact, mineralogists often refer to "books of mica".

Diamond and graphite provide examples of cleavage. Each is composed solely of a single element, carbon. In diamond, each carbon atom is bonded to four others in a tetrahedral pattern with short covalent bonds. The planes of weakness (cleavage planes) in a diamond are in four directions, following the faces of the octahedron. In graphite, carbon atoms are contained in layers in a hexagonal pattern where the covalent bonds are shorter (and thus even stronger) than those of diamond. However, each layer is connected to the other with a longer and much weaker van der Waals bond. This gives graphite a single direction of cleavage, parallel to the basal pinacoid. So weak is this bond that it is broken with little force, giving graphite a slippery feel as layers shear apart. As a result, graphite makes an excellent dry lubricant.

While all single crystals will show some tendency to split along atomic planes in their crystal structure, if the differences between one direction or another are not large enough, the mineral will not display cleavage. Corundum, for example, displays no cleavage. (Full article...) -

Image 18

A crystalline solid: atomic resolution image of strontium titanate. Brighter spots are columns of strontium atoms and darker ones are titanium-oxygen columns.

Crystallography is the branch of science devoted to the study of molecular and crystalline structure and properties. The word crystallography is derived from the Ancient Greek word κρύσταλλος (krústallos; "clear ice, rock-crystal"), and γράφειν (gráphein; "to write"). In July 2012, the United Nations recognised the importance of the science of crystallography by proclaiming 2014 the International Year of Crystallography.

Crystallography is a broad topic, and many of its subareas, such as X-ray crystallography, are themselves important scientific topics. Crystallography ranges from the fundamentals of crystal structure to the mathematics of crystal geometry, including those that are not periodic or quasicrystals. At the atomic scale it can involve the use of X-ray diffraction to produce experimental data that the tools of X-ray crystallography can convert into detailed positions of atoms, and sometimes electron density. At larger scales it includes experimental tools such as orientational imaging to examine the relative orientations at the grain boundary in materials. Crystallography plays a key role in many areas of biology, chemistry, and physics, as well new developments in these fields. (Full article...) -

Image 19

Gypsum is a soft sulfate mineral composed of calcium sulfate dihydrate, with the chemical formula CaSO4·2H2O. It is widely mined and is used as a fertilizer and as the main constituent in many forms of plaster, drywall and blackboard or sidewalk chalk. Gypsum also crystallizes as translucent crystals of selenite. It forms as an evaporite mineral and as a hydration product of anhydrite. The Mohs scale of mineral hardness defines gypsum as hardness value 2 based on scratch hardness comparison.

Fine-grained white or lightly tinted forms of gypsum known as alabaster have been used for sculpture by many cultures including Ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Ancient Rome, the Byzantine Empire, and the Nottingham alabasters of Medieval England. (Full article...) -

Image 20

Chalcopyrite (/ˌkælkəˈpaɪˌraɪt, -koʊ-/ KAL-kə-PY-ryte, -koh-) is a copper iron sulfide mineral and the most abundant copper ore mineral. It has the chemical formula CuFeS2 and crystallizes in the tetragonal system. It has a brassy to golden yellow color and a hardness of 3.5 to 4 on the Mohs scale. Its streak is diagnostic as green-tinged black.

On exposure to air, chalcopyrite tarnishes to a variety of oxides, hydroxides, and sulfates. Associated copper minerals include the sulfides bornite (Cu5FeS4), chalcocite (Cu2S), covellite (CuS), digenite (Cu9S5); carbonates such as malachite and azurite, and rarely oxides such as cuprite (Cu2O). It is rarely found in association with native copper. Chalcopyrite is a conductor of electricity.

Copper can be extracted from chalcopyrite ore using various methods. The two predominant methods are pyrometallurgy and hydrometallurgy, the former being the most commercially viable. (Full article...) -

Image 21Beachy Head is a part of the extensive Southern England Chalk Formation.

Chalk is a soft, white, porous, sedimentary carbonate rock. It is a form of limestone composed of the mineral calcite and originally formed deep under the sea by the compression of microscopic plankton that had settled to the sea floor. Chalk is common throughout Western Europe, where deposits underlie parts of France, and steep cliffs are often seen where they meet the sea in places such as the Dover cliffs on the Kent coast of the English Channel.

Chalk is mined for use in industry, such as for quicklime, bricks and builder's putty, and in agriculture, for raising pH in soils with high acidity. It is also used for "blackboard chalk" for writing and drawing on various types of surfaces, although these can also be manufactured from other carbonate-based minerals, or gypsum. (Full article...) -

Image 22A ruby crystal from Dodoma Region, Tanzania

Ruby is a pinkish red to blood-red colored gemstone, a variety of the mineral corundum (aluminium oxide). Ruby is one of the most popular traditional jewelry gems and is very durable. Other varieties of gem-quality corundum are called sapphires. Ruby is one of the traditional cardinal gems, alongside amethyst, sapphire, emerald, and diamond. The word ruby comes from ruber, Latin for red. The color of a ruby is due to the element chromium.

Some gemstones that are popularly or historically called rubies, such as the Black Prince's Ruby in the British Imperial State Crown, are actually spinels. These were once known as "Balas rubies".

The quality of a ruby is determined by its color, cut, and clarity, which, along with carat weight, affect its value. The brightest and most valuable shade of red, called blood-red or pigeon blood, commands a large premium over other rubies of similar quality. After color follows clarity: similar to diamonds, a clear stone will command a premium, but a ruby without any needle-like rutile inclusions may indicate that the stone has been treated. Ruby is the traditional birthstone for July and is usually pinker than garnet, although some rhodolite garnets have a similar pinkish hue to most rubies. The world's most valuable ruby to be sold at auction is the Sunrise Ruby, which sold for US$34.8 million. (Full article...) -

Image 23

Corundum is a crystalline form of aluminium oxide (Al2O3) typically containing traces of iron, titanium, vanadium, and chromium. It is a rock-forming mineral. It is a naturally transparent material, but can have different colors depending on the presence of transition metal impurities in its crystalline structure. Corundum has two primary gem varieties: ruby and sapphire. Rubies are red due to the presence of chromium, and sapphires exhibit a range of colors depending on what transition metal is present. A rare type of sapphire, padparadscha sapphire, is pink-orange.

The name "corundum" is derived from the Tamil-Dravidian word kurundam (ruby-sapphire) (appearing in Sanskrit as kuruvinda).

Because of corundum's hardness (pure corundum is defined to have 9.0 on the Mohs scale), it can scratch almost all other minerals. It is commonly used as an abrasive on sandpaper and on large tools used in machining metals, plastics, and wood. Emery, a variety of corundum with no value as a gemstone, is commonly used as an abrasive. It is a black granular form of corundum, in which the mineral is intimately mixed with magnetite, hematite, or hercynite.

In addition to its hardness, corundum has a density of 4.02 g/cm3 (251 lb/cu ft), which is unusually high for a transparent mineral composed of the low-atomic mass elements aluminium and oxygen. (Full article...) -

Image 24

Garnets ( /ˈɡɑːrnɪt/) are a group of silicate minerals that have been used since the Bronze Age as gemstones and abrasives.

All species of garnets possess similar physical properties and crystal forms, but differ in chemical composition. The different species are pyrope, almandine, spessartine, grossular (varieties of which are hessonite or cinnamon-stone and tsavorite), uvarovite and andradite. The garnets make up two solid solution series: pyrope-almandine-spessartine (pyralspite), with the composition range [Mg,Fe,Mn]3Al2(SiO4)3; and uvarovite-grossular-andradite (ugrandite), with the composition range Ca3[Cr,Al,Fe]2(SiO4)3. (Full article...) -

Image 25

Kaolinite (/ˈkeɪ.ələˌnaɪt, -lɪ-/ KAY-ə-lə-nyte, -lih-; also called kaolin) is a clay mineral, with the chemical composition Al2Si2O5(OH)4. It is a layered silicate mineral, with one tetrahedral sheet of silica (SiO4) linked through oxygen atoms to one octahedral sheet of alumina (AlO6).

Kaolinite is a soft, earthy, usually white, mineral (dioctahedral phyllosilicate clay), produced by the chemical weathering of aluminium silicate minerals like feldspar. It has a low shrink–swell capacity and a low cation-exchange capacity (1–15 meq/100 g).

Rocks that are rich in kaolinite, and halloysite, are known as kaolin (/ˈkeɪ.əlɪn/) or china clay. In many parts of the world kaolin is colored pink-orange-red by iron oxide, giving it a distinct rust hue. Lower concentrations of iron oxide yield the white, yellow, or light orange colors of kaolin. Alternating lighter and darker layers are sometimes found, as at Providence Canyon State Park in Georgia, United States.

Kaolin is an important raw material in many industries and applications. Commercial grades of kaolin are supplied and transported as powder, lumps, semi-dried noodle or slurry. Global production of kaolin in 2021 was estimated to be 45 million tonnes, with a total market value of US $4.24 billion. (Full article...)

Selected mineralogist

-

Image 1Arthur Edmund Seaman (December 29, 1858 – July 10, 1937) was a professor at the Michigan College of Mines (now Michigan Technological University) and curator of the A. E. Seaman Mineral Museum which bears his name. (Full article...)

-

Image 2

George R. Rossman is an American mineralogist and the Professor of Mineralogy at the California Institute of Technology. (Full article...) -

Image 3

Johannes Martin Bijvoet ForMemRS (23 January 1892, Amsterdam – 4 March 1980, Winterswijk) was a Dutch chemist and crystallographer at the van 't Hoff Laboratory at Utrecht University. He is famous for devising a method of establishing the absolute configuration of molecules. In 1946, he became member of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.

The concept of tetrahedrally bound carbon in organic compounds stems back to the work by van 't Hoff and Le Bel in 1874. At this time, it was impossible to assign the absolute configuration of a molecule by means other than referring to the projection formula established by Fischer, who had used glyceraldehyde as the prototype and assigned randomly its absolute configuration. (Full article...) -

Image 4Werner Schreyer (14 November 1930 in Nuremberg; 12 February 2006 in Bochum) was a German mineralogist and experimental metamorphic petrologist. Schreyer completed his undergraduate work in geology and petrology at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, obtained his doctorate from the University of Munich in 1957, and in 1966 received his Habilitation from the University of Kiel. He was a professor at Ruhr University Bochum from 1966 to 1996. In 2002 Schreyer became the first German to be awarded the Mineralogical Society of America's highest honor, the Roebling Medal. Schreyer was a leading expert on phase relations in the MgO–Al2O3–SiO2–H2O (MASH) system, specializing in cordierite and minerals with equivalent chemical compositions, and high pressure and ultra high-pressure metamorphic mineral assemblages.

The mineral Schreyerite (V2Ti3O9) was named after Schreyer. (Full article...) -

Image 5

Georges Friedel (19 July 1865 – 11 December 1933) was a French mineralogist and crystallographer. (Full article...) -

Image 6Adolf Knop (12 January 1828, in Altenau – 27 December 1893, in Karlsruhe) was a German geologist and mineralogist.

He studied mathematics and sciences at the University of Göttingen, where he was a pupil of chemist Friedrich Wohler and mineralogist Johann Friedrich Ludwig Hausmann. From 1849 he taught classes at the vocational school in Chemnitz. In 1857 he became an associate professor of geology and mineralogy at the University of Giessen, where in 1863 he attained a full professorship. In 1866 he relocated to Karlsruhe as a professor at the Polytechnic school. In 1878 he succeeded Moritz August Seubert as manager of the Grand Ducal Natural History Cabinet. (Full article...) -

Image 7

Johan Georg Forchhammer (26 July 1794 – 14 December 1865) was a Danish mineralogist and geologist. (Full article...) -

Image 8

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/24–79), known in English as Pliny the Elder (/ˈplɪni/ PLIN-ee), was a Roman author, naturalist, natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic Naturalis Historia (Natural History), a comprehensive thirty-seven-volume work covering a vast array of topics on human knowledge and the natural world, which became an editorial model for encyclopedias. He spent most of his spare time studying, writing, and investigating natural and geographic phenomena in the field.

Among Pliny's greatest works was the twenty-volume Bella Germaniae ("The History of the German Wars"), which is no longer extant. Bella Germaniae, which began where Aufidius Bassus' Libri Belli Germanici ("The War with the Germans") left off, was used as a source by other prominent Roman historians, including Plutarch, Tacitus, and Suetonius. Tacitus may have used Bella Germaniae as the primary source for his work, De origine et situ Germanorum ("On the Origin and Situation of the Germans"). (Full article...) -

Image 9

Alfred Des Cloizeaux

Alfred Louis Olivier Legrand Des Cloizeaux (17 October 1817 – 6 May 1897) was a French mineralogist.

Des Cloizeaux was born at Beauvais, in the department of Oise. He studied with Jean-Baptiste Biot at the Collège de France. He became professor of mineralogy at the École Normale Supérieure and afterwards at the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle in Paris. He studied the geysers of Iceland, and wrote also on the classification of some of the eruptive rocks. (Full article...) -

Image 10

Anders Jahan Retzius (3 October 1742 – 6 October 1821) was a Swedish chemist, botanist and entomologist. (Full article...) -

Image 11

Arthur Aikin (19 May 1773 – 15 April 1854) was an English chemist, mineralogist and scientific writer, and was a founding member of the Chemical Society (now the Royal Society of Chemistry). He first became its treasurer in 1841, and later became the society's second president. (Full article...) -

Image 12

George Gibbs (January 7, 1776 – August 6, 1833) was an American mineralogist and mineral collector. The mineral gibbsite is named after him. (Full article...) -

Image 13Konrad Oebbeke (2 November 1853, Hildesheim – 1 February 1932) was a German geologist and mineralogist.

He studied at the Universities of Heidelberg and Erlangen, obtaining his doctorate at the University of Würzburg in 1877. Afterwards he worked as an assistant to the Geological Survey of Bavaria. He served as privat-docent at the University of Munich, later becoming a professor of mineralogy and geology at Erlangen (1887).

From 1895 to 1927 he was a professor at the Technische Hochschule of Munich. (Full article...) -

Image 14

University of Michigan faculty portrait

Edward Henry Kraus (1875–1973) was a professor of mineralogy at the University of Michigan and also served as Dean of the Summer Session, 1915–1933, Dean of the College of Pharmacy, 1923–1933, and Dean of the College of Literature, Science and the Arts, 1933–1945. (Full article...) -

Image 15Dr. E-An Zen (任以安) was born in Peking, China, May 31, 1928, and came to the U.S. in 1946. He became a citizen in 1963. Since 1990 he was adjunct professor at the University of Maryland. He died on March 29, 2014, at the age of 85.

He has contributed articles to professional journals and is a fellow of the Geological Society of America (Councillor, 1985–88, 1990–93; President, 1991–92); the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, the Mineralogical Society of America (Council, 1974–77;Pres., 1975–76). He is a member of the Geological Society of Washington (Pres. 1973), the National Academy of Sciences, and the Mineralogical Association of Canada. Zen has been active in programs to bring geological knowledge to the general public. (Full article...) -

Image 16

Wilhelm Karl Ritter von Haidinger (or Wilhelm von Haidinger, or most often Wilhelm Haidinger) (5 February 1795 – 19 March 1871) was an Austrian mineralogist. (Full article...) -

Image 17Adolarius Jacob Forster (1739–1806) was a Prussian mineralogist and dealer in display specimen minerals. The Forster family left Yorkshire in 1649 and settled in Prussia. Adolarius Jacob Forster began dealing in mineral specimens around 1766, at the age of 27. He continued in that profession for 40 years and travelled widely. He had premises in London, Paris and St. Petersburg. The Covent Garden, London shop and one in Soho was run by his wife. His brother, Ingham Henry Forster (1725–1782) ran the business in Paris. Auction catalogues for sales in Paris were written by Romé de l'Isle.

He was related to Johann Georg Adam Forster and Johann Reinhold Forster and his sister married the London dealer naturalist George Humphrey at St-Martin-in-the-Fields, London on August 16, 1768. In 1802 Forster sold a collection to the museum of the St Petersburg Mining Institute, under the auspices of the Emperor of All Russia Alexander I. He spent the last ten years of his life in Russia, and died in St. Petersburg in 1806. The dealership was taken over by his nephew John Henry Heuland. (Full article...) -

Image 18Anselmus de Boodt or Anselmus Boetius de Boodt (Bruges, 1550 - Bruges, 21 June 1632) was a Flemish humanist naturalist, Rudolf II physician's gemologist. Along with the German known as Georgius Agricola with mineralogy, de Boodt was responsible for establishing modern gemology. De Boodt was an avid gems and minerals collector who travelled widely to various mining regions in Belgium, Germany, Bohemia and Silesia to collect samples. His definitive work on the subject was the Gemmarum et Lapidum Historia (1609).

De Boodt was also a gifted draughtsman who made many natural history illustrations and developed a natural history taxonomy. (Full article...) -

Image 19Charles Louis Christ (March 12, 1916 – June 29, 1980) was an American scientist, geochemist and mineralogist. (Full article...)

-

Image 20Vittorio Simonelli (May 1860, in Arezzo – 9 February 1929, in San Quirico d'Orcia) was an Italian geologist and paleontologist. (Full article...)

-

Image 21

Friedrich Rinne

Friedrich Wilhelm Berthold Rinne (16 March 1863 in Osterode am Harz – 12 March 1933 in Freiburg im Breisgau) was a German mineralogist, crystallographer and petrographer. (Full article...) -

Image 22Westgarth Forster (1772–1835) was a geologist and mining engineer, mine agent at Allenheads and Coalcleugh (Northumberland) over two decades and then a consultant surveyor and author. He was the son of a mining engineer (Westgarth Forster the elder, 1738–1797), and was born in Coalcleugh, Northumberland. (Full article...)

-

Image 23

James Smithson FRS (c. 1765 – 27 June 1829) was a British chemist and mineralogist. He published numerous scientific papers for the Royal Society during the early 1800s as well as defining calamine, which would eventually be renamed after him as "smithsonite". He was the founding donor of the Smithsonian Institution, which also bears his name.

Born in Paris, France, as the illegitimate child of Elizabeth Hungerford Keate Macie and Hugh Percy (born Hugh Smithson), the 1st Duke of Northumberland, he was given the French name Jacques-Louis Macie. His birth date was not recorded and the exact location of his birth is unknown; it is possibly in the Pentemont Abbey. Shortly after his birth he naturalized to Britain where his name was anglicized to James Louis Macie. He adopted his father's original surname of Smithson in 1800, following his mother's death. He attended university at Pembroke College, Oxford in 1782, eventually graduating with a Master of Arts in 1786. As a student he participated in a geological expedition to Scotland and studied chemistry and mineralogy. Highly regarded for his blowpipe analysis and his ability to work in miniature, Smithson spent much of his life traveling extensively throughout Europe; he published some 27 papers in his life. (Full article...) -

Image 24Haldor Frederik Axel Topsøe (29 April 1842 in Skælskør, Slagelse Municipality, Denmark – 31 December 1935 in Frederiksberg, Denmark) was a Danish chemist and crystallographer. He is grandfather of the engineer Haldor Topsøe (1913–2013) who has got his name from his grandfather, and great-grandfather of the mathematician Flemming Topsøe (born 25 August 1938) and the engineer Henrik Topsøe (born 10 August 1944).

Topsøe took Magisterkonferens in chemistry in 1866 and doctorate for a chemical-crystallographical work of selenium-sour salts. He worked as assistant at the Natural History Museum 1863–1867 and at the chemistry laboratory of University of Copenhagen 1867–1873. In 1872, he received a gold medal of Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters, of which he was member from 1877, for a great crystallographical-optical work together with the physicist Christian Christiansen (1843–1917). He worked as chemistry teacher at the Royal Danish Military Academy 1876–1902 where he founded a new laboratory where he continued his science works. In 1884 he participated in the oceanographic expedition to west Greenland on the gunboat HDMS Fylla. He was member of the Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters from 1892. (Full article...) -

Image 25William "Bill" Wallace Pinch (August 15, 1940 – April 1, 2017) was a mineralogist from Rochester, New York. The Mineralogical Association of Canada has an award named after him, the Pinch Medal, "to recognize major and sustained contributions to the advancement of mineralogy by members of the collector-dealer community."

The Pinch Medal has been awarded to a deserving mineralogist every other year since it was first awarded to Pinch in 2001, and is given at the Tucson Mineral Show in February.

Pinch was also a notable mineral collector. His collection was sold in 1989 to the Canadian Museum of Nature for $US 3.5 million, and will be documented in a book to be published in 2018. (Full article...)

Related portals

Get involved

For editor resources and to collaborate with other editors on improving Wikipedia's Minerals-related articles, see WikiProject Rocks and minerals.

General images

-

Image 2Mohs hardness kit, containing one specimen of each mineral on the ten-point hardness scale (from Mohs scale)

-

Image 3Red cinnabar (HgS), a mercury ore, on dolomite. (from Mineral)

-

Image 5Muscovite, a mineral species in the mica group, within the phyllosilicate subclass (from Mineral)

-

Image 7Sphalerite crystal partially encased in calcite from the Devonian Milwaukee Formation of Wisconsin (from Mineral)

-

Image 8Gypsum desert rose (from Mineral)

-

Image 10Asbestiform tremolite, part of the amphibole group in the inosilicate subclass (from Mineral)

-

Image 11Pink cubic halite (NaCl; halide class) crystals on a nahcolite matrix (NaHCO3; a carbonate, and mineral form of sodium bicarbonate, used as baking soda). (from Mineral)

-

Image 12When minerals react, the products will sometimes assume the shape of the reagent; the product mineral is termed a pseudomorph of (or after) the reagent. Illustrated here is a pseudomorph of kaolinite after orthoclase. Here, the pseudomorph preserved the Carlsbad twinning common in orthoclase. (from Mineral)

-

Image 13An example of elbaite, a species of tourmaline, with distinctive colour banding. (from Mineral)

-

Image 14Perfect basal cleavage as seen in biotite (black), and good cleavage seen in the matrix (pink orthoclase). (from Mineral)

-

Image 16Schist is a metamorphic rock characterized by an abundance of platy minerals. In this example, the rock has prominent sillimanite porphyroblasts as large as 3 cm (1.2 in). (from Mineral)

-

Image 17Epidote often has a distinctive pistachio-green colour. (from Mineral)

-

Image 20Hübnerite, the manganese-rich end-member of the wolframite series, with minor quartz in the background (from Mineral)

-

Image 23Native gold. Rare specimen of stout crystals growing off of a central stalk, size 3.7 x 1.1 x 0.4 cm, from Venezuela. (from Mineral)

-

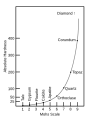

Image 24Mohs Scale versus Absolute Hardness (from Mineral)

-

Image 25Diamond is the hardest natural material, and has a Mohs hardness of 10. (from Mineral)

-

Image 26Black andradite, an end-member of the orthosilicate garnet group. (from Mineral)

Did you know ...?

- ... that the rare mineral Matlockite (PbFCl) (pictured) is named after a town in Derbyshire?

- ...that the amorphous phosphate mineral santabarbaraite was named after the Italian mining district Santa Barbara where it was discovered in 2003, but its name also honors Saint Barbara, the patron saint of miners?

- ...that when yellow crystals of mosesite, a very rare mineral found in deposits of mercury, are heated to 186 °C (367 °F), they become isotropic?

Subcategories

Topics

| Overview | ||

|---|---|---|

| Common minerals | ||

Ore minerals, mineral mixtures and ore deposits | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ores |

| ||||||||

| Deposit types | |||||||||

| Borates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbonates | |||||

| Oxides |

| ||||

| Phosphates | |||||

| Silicates | |||||

| Sulfides | |||||

| Other |

| ||||

| Crystalline | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cryptocrystalline | |||||||

| Amorphous | |||||||

| Miscellaneous | |||||||

| Notable varieties |

| ||||||

| Oxide minerals |

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silicate minerals | |||||

| Other | |||||

Gemmological classifications by E. Ya. Kievlenko (1980), updated | |||||||||

| Jewelry stones |

| ||||||||

| Jewelry-Industrial stones |

| ||||||||

| Industrial stones |

| ||||||||

Mineral identification | |

|---|---|

| "Special cases" ("native elements and organic minerals") |

|

|---|---|

| "Sulfides and oxides" |

|

| "Evaporites and similars" |

|

| "Mineral structures with tetrahedral units" (sulfate anion, phosphate anion, silicon, etc.) |

|

Associated Wikimedia

The following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

-

Commons

Free media repository -

Wikibooks

Free textbooks and manuals -

Wikidata

Free knowledge base -

Wikinews

Free-content news -

Wikiquote

Collection of quotations -

Wikisource

Free-content library -

Wikiversity

Free learning tools -

Wiktionary

Dictionary and thesaurus

References

- Pages using Template:Post-nominals with customized linking

- Manually maintained portal pages from May 2019

- All manually maintained portal pages

- Portals with triaged subpages from May 2019

- All portals with triaged subpages

- Portals with named maintainer

- Automated article-slideshow portals with 31–40 articles in article list

- Automated article-slideshow portals with 201–500 articles in article list

- Portals needing placement of incoming links