Qalaherriaq

Erasmus Augustine Kallihirua | |

|---|---|

| Qalaherriaq | |

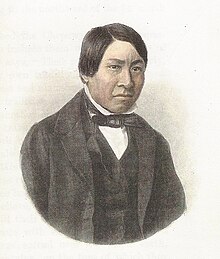

1855 drawing, based on a now-lost photograph | |

| Born | c. 1834 |

| Died | June 14, 1856 St. John's, Newfoundland Colony |

| Other names | Erasmus York, Kalli |

| Signature | |

Qalaherriaq (Inuktun pronunciation: [qalahəχːiɑq], c. 1834 – June 14, 1856), baptized as Erasmus Augustine Kallihirua,[a] was an Inughuit hunter from Cape York, Greenland. He was recruited in 1850 as an interpreter by the crew of the British survey barque HMS Assistance during the search for John Franklin's lost Arctic expedition. He guided the ship to Wolstenholme Fjord to investigate rumors of a massacre of Franklin's crew, but only found the corpses of local Inughuit and crew from an unrelated British vessel. With the help of the crew of the vessel, he produced accurate maps of his homeland. Although Assistance initially planned to return him to his family after the expedition, poor sea conditions made landing at Cape York impossible, and he was taken to England and placed under the care of the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge (SPCK).

Enrolled at St Augustine's College in Canterbury, England, Qalaherriaq studied English and Christianity for several years. He was appointed by the Bishop of Newfoundland Edward Feild to accompany him on religious missions to the Inuit of Labrador. He arrived at St. John's in October 1855, and began studying at the Theological Institute. Plagued by illness since his time aboard Assistance, he died from complications of long-term tuberculosis in June 1856, shortly before he was scheduled to travel to Labrador. A posthumous biography, Kalli, the Esquimaux Christian, was published by the SPCK shortly after his death. Inughuit oral histories, collected by Knud Rasmussen in the early 20th century, describe him as the victim of an abduction by the British, and relate that his mother mourned him without learning of his fate.

Name

[edit]Qalaherriaq was known by various names. Qalaherriaq or Qalaherhuaq are approximations of his name's pronunciation in his native dialect of Inuktun, rendered as Qalasirsuaq ([qalasəsːuɑq]) in standard Greenlandic. This was rendered as Kallihirua in contemporary sources, and frequently abbreviated "Kalli".[1] He was named Erasmus York (after Captain Erasmus Ommanney and Cape York),[2] before his baptism in 1853 as Erasmus Augustine Kallihirua. Other spellings of his name include Caloosa, Calahierna, Kalersik, Ka'le'sik, Qalaseq, and Kalesing.[1]

Early life and background

[edit]

Qalaherriaq was born around 1834[b] to Qisunnguaq and Saattoq,[c] members of an Inughuit band near Cape York and Wolstenholme Fjord in northwestern Greenland.[4] He had a younger sister, and perhaps another younger sibling, both of whose names are unknown.[5] His band, situated near auk-hunting grounds,[6] was encountered by various ships searching for a lost British exploring mission.[7]

Search for Franklin's expedition

[edit]In 1845, Sir John Franklin commanded an expedition attempting to transit the final uncharted sections of the Northwest Passage in what is now western Nunavut. The two warships under Franklin's command, HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, were trapped by ice in the Victoria Strait. The ships were abandoned in April 1848, and all remaining crew members presumably died while attempting to traverse the Canadian Arctic mainland. In March 1848, when the expedition had been out of contact for several years, the Royal Navy's Board of Admiralty launched a series of expeditions to locate whatever remained of Franklin's expedition and determine their fate.[8]

Four concurrent search expeditions were outfitted in 1850 following lobbying by Franklin's widow, Jane, who refused to accept that her husband was almost certainly dead.[8][7] The first of these expeditions were headed by the barques HMS Resolute and HMS Assistance, accompanied by the steam tenders HMS Pioneer and HMS Intrepid. The second involved only two ships, the brigs HMS Lady Franklin and HMS Sophia. Privately funded expeditions of the schooners Prince Albert (commanded by Commander Charles Forsyth) and Felix (commanded by Sir John Ross) joined those funded by the Admiralty.[7]

On August 12, 1850, HMS Lady Franklin and HMS Sophia, commanded by whaler and explorer William Penny, reached the coast of Cape York. Upon sighting an approaching Inughuit kayak, Sophia anchored. The three men aboard the kayak were invited on deck to meet with Penny's interpreter, Johan Carl Petersen, a Dane from Upernavik. Petersen inquired for information relating to Franklin's expedition, but the relatively large number of European ships previously sighted in the region, coupled with the Inughuit's great excitement aboard the vessel, resulted in no useful information, and the Inughuit returned to shore.[7]

Cape York landing

[edit]

The following day, Prince Albert and HMS Assistance spotted the same group of Inughuit. A landing party including Charles Forsyth and Captain Erasmus Ommanney went to shore aboard HMS Intrepid, followed by the other ships. They were greeted by two young men, including Qalaherriaq.[9][10] However, none of the landing party could speak Inuktun, and were unable to communicate with the band ashore. Shortly afterwards, the party was joined by Sir John Ross and his Kalaallit interpreter Adam Beck, who had arrived aboard Felix.[11] After a long conversation, the only ship that could be readily identified from the Inughuit accounts was North Star, a supply ship which had passed through the region during another search for Franklin's expedition.[11]

Upon the officers' return to their ships, Beck became noticeably distressed. He explained that the Inughuit mentioned an additional ship that had passed through the area in 1846 staffed by naval officers, which was massacred by another Inughuit band while camping ashore at Wolstenholme Fjord. After Ommanney and Petersen were informed of the story, they had Beck repeat the story to various officers. Ommanney boarded Lady Franklin and relayed the story to Penny. Ommanney, Penny and Petersen travelled back to Cape York aboard Intrepid, intending to confirm the story and acquire a local interpreter. When the Inughuit repeated the same information about North Star to the explorers and denied any violence against the British, Petersen was convinced that Beck had confused the information about North Star with Franklin's expedition. Ommaney recruited Qalaherriaq to serve as an interpreter.[5][10][12]

Interpreter service

[edit]

Ommanney's diary described Qalaherriaq as readily volunteering to go with the expedition, without even returning to camp to gather his possessions. Nineteenth century sources state that he was fully ready to "remain under the captain's own personal care, and be with him always", and that he had stoically accepted his role as an interpreter due to a lack of surviving family. However, this account has been heavily disputed by later scholarship.[13] Significant contradictions exist between period descriptions of Qalaherriaq's decision to volunteer. Explorer William Parker Snow's 1851 account, Voyage of the Prince Albert in Search of Sir John Franklin, describes him as a "young man without father or mother", while Petersen's 1857 Erindringer Fra Polarlandene describes him as being unbothered by leaving his mother.[5][13] Petersen's account claims that Qalaherriaq agreed to a brief term of service, and was originally supposed to be returned to his family after guiding the mission to Wolstenholme Fjord.[14]

After Qalaherriaq and the explorers boarded Intrepid, they were joined by Beck, Ross, and Forsyth, alongside Horatio Austin of HMS Resolute and Sherard Osborn of HMS Pioneer. Upon cross-questioning, Beck repeated what he claimed the Inughuit had told him, but Qalaherriaq insisted that he was lying. Communication between the two was limited due to linguistic differences between Qalaherriaq's Inuktun and Beck's Greenlandic. Qalaherriaq was able to communicate with Petersen much easier than with Beck. The officers eventually became convinced that Beck was incorrect, but continued towards Wolstenholme Fjord.[10]

When asked by Captain Ommanney to sketch the coast, he took up a pencil, a thing he had never seen before, and delineated the coast-line from Pikierlu to Cape York, with astonishing accuracy, making marks to indicate all the islands, remarkable cliffs, glaciers, and hills, and giving all their native names.

Clements Markham, Arctic Geography and Ethnology, 1875[15]

Upon transfer to Assistance, Qalaherriaq was washed and dressed in European clothing. He was given the name Erasmus York, although continued to be called variations of his birth name while aboard. He was seen as a curiosity by the crew, who recruited him to participate in the "Royal Arctic Theatre", a trope of theatrical performances. Ommanney described him as "an interesting specimen of uncivilised life".[16][17] Qalaherriaq was the subject of a satirical article published in the Northern Lights, a ship newspaper published aboard Assistance, where he is depicted as praising European civilization, while making various naïve and childlike statements about ship life, including a joke about him misidentifying sailors cross-dressing during a masquerade as shamanic spirits.[18][19]

While on board Assistance, Qalaherriaq was said to have drawn several detailed maps of the surrounding fjords. While he was described as drawing them single-handedly, biographer Peter Martin states that Qalaherriaq "certainly did not do so alone".[20] The maps were drawn according to European cartography, and do not reflect Inuit geography or mapping, such as the Ammassalik wooden maps. Geographer Clements Markham, the Assistance midshipman, heavily praised the map in his 1875 Arctic Geography and Ethnology, echoing earlier European praise of Inuit geographical knowledge.[21]

Wolstenholme Fjord

[edit]

Qalaherriaq guided Assistance to Wolstenholme Fjord where the Europeans investigated the claims of a massacre of the Franklin expedition.[22] The area was devastated due to a recent epidemic. When the crew encountered several abandoned igloos at the site of Uummannaq (now Pituffik), they found a heaped pile of seven bodies. The survivors were assumed to have fled the area without burying the dead due to the disease outbreak. The crew excavated several graves, finding the bodies of both Inuit and British seamen from North Star who had contracted the disease.[6][22]

An officer examined a grave and removed a narwhal tusk spear placed atop the grave, a type of Inughuit grave artifact commonly looted by British explorers for the collections of anthropological museums. Qalaherriaq cried and begged him to put the spear back, recognizing the grave as being that of his father, Qisunnguaq. The grave was repaired by another officer and the spear, considered in Inughuit customs to be used by the dead for protection in the afterlife, was returned.[6][22]

With sea conditions rendering return to Cape York impossible, Assistance crossed Baffin Bay and wintered at Griffith Island, near the present location of Resolute.[4] Icebergs continued to pose a threat the following spring, and the ship began the return trip to England without returning Qalaherriaq to his family.[6]

Early 20th century Inughuit oral histories, recorded by Knud Rasmussen, describe Qalaherriaq as being abducted by the explorers, with his mother mourning his disappearance without ever learning of his fate.[23] The loss of an adolescent son, expected to hunt for the family, would place a great material burden on his mother and siblings. This was especially true during an era marked by severe hardship for the Inughuit, characterized by population decline, widespread disease outbreaks, and extreme isolation from outside trade or contact.[3][24][25]

England

[edit]

Qalaherriaq arrived in England in the autumn of 1851 aboard Assistance, and was brought to the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.[4] In October 1851, he visited the Great Exhibition in London alongside Reverend George Murray, secretary of the Society, one of a small group of clergy and officers who served as caretakers to Qalaherriaq.[26][27]

In around late 1851,[28] Qalaherriaq sat for a life-size double portrait by an unknown artist, which some decades later was donated for display at the Royal Navy College in Greenwich.[29] The double portrait was made according to contemporary European race science, and features emphasis on phrenological and racialized features such as his cranial anatomy and skin tone. Biographers Ingeborg Høvik and Axel Jeremiassen described the portrait as appearing to Victorians as a "visual embodiment of a lower race" which associates the Inuit with the theorized "Mongolian race".[30] He also sat for a photograph while in England, now lost. An illustration based on it is featured in an 1855 edition of James C. Prichard's The Natural History of Man.[31]

I be in England long time none very well – very bad weather ... very bad cough – I very sorry – very bad. Weather dreadful. Country very different – another day cold another day [h]ot. I miserable.

Qalaherriaq, letter, April 1853[30]

In November, at the recommendation of the Admiralty and the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, Qalaherriaq was placed in St Augustine's College, a Church of England missionary college in Canterbury. Here he learned to read and write while receiving a religious education, and served as an apprentice to a local tailor. From 1852 to 1853 he was interviewed by Captain John Washington for a revised edition of his Greenlandic linguistics text, Eskimaux and English Vocabulary, for the Use of the Arctic Expeditions.[4] By September 1852, he had made some progress in English but struggled with reading. He was reported to greatly enjoy writing, and made friendships with the children in his spelling classes.[32] Qalaherriaq had suffered from a chronic illness since his time on Assistance. He coughed frequently, and by the spring of 1853 was bedridden for several days during a period of poor weather.[30] On November 27, 1853, he was baptized as Erasmus Augustine Kallihirua at St. Martin's Church in Canterbury, in a ceremony attended by Ommanney and various ministers and clergy, alongside various members of "the poorer class to whom Kalli is well known".[33]

Newfoundland and death

[edit]Appointed by Edward Feild, the Bishop of Newfoundland and the Warden of St Augustine's, Qalaherriaq was sent to the Newfoundland Colony to assist missionary efforts among the Inuit of Labrador. To support this, he was given a £25 per year stipend (equivalent to £3,000 in 2023).[34] He arrived at St John's, Newfoundland, on October 2, 1855. Although all were Inuit languages, Qalaherriaq's dialect of Greenlandic was a distinct language from the Nunatsiavummiutitut dialect of Eastern Canadian Inuktitut, and Qalaherriaq struggled to communicate with a Moravian missionary from Labrador.[35] He attended the Theological Institute (now Queen's College, part of the Memorial University).[4] While in Newfoundland, he practiced ice skating, but continued to suffer from chronic illness.[36]

Qalaherriaq planned to accompany the Bishop of Newfoundland on missionary work to Labrador in the summer of 1856. However, after he went swimming in cold water at St. John's, his health declined rapidly. Bedridden for a week, he died on June 14, 1856.[4] An autopsy done at St. John's in the following weeks concluded that he died of heart failure associated with long-term tuberculosis. His body displayed common symptoms of the disease, including inflamed lymph nodes, blackened lungs, and an "enormously enlarged" heart.[37]

A short biography, Kalli, the Esquimaux Christian, was written by Reverend Murray in 1856 and published by the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. Murray based the book off his personal experiences alongside contributions from Qalaherriaq's other British caretakers. As the secretary of the Society, he had previously worked to organize Qalaherriaq's life and education in England. The memoir became the main primary source on Qalaherriaq's life, alongside the various accounts of the 1850 search expeditions.[26][38]

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Høvik & Jeremiassen 2023, pp. 976–977.

- ^ Harper, Kenn (June 17, 2005). "Taissumani: A Day in Arctic History June 14, 1856 – Erasmus Augustine Kallihirua dies in St. John's". Nunatsiaq News. Archived from the original on December 5, 2023. Retrieved December 5, 2023.

- ^ a b Høvik & Jeremiassen 2023, p. 991.

- ^ a b c d e f Holland, Clive (1985). "Kallihirua". Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. 8. University of Toronto. Archived from the original on January 10, 2024. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ a b c Høvik & Jeremiassen 2023, pp. 990–991.

- ^ a b c d Malaurie 2003, p. 58.

- ^ a b c d Martin 2023, pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b Marsh, James H.; Beattie, Owen; de Bruin, Tabitha (March 8, 2018). "Franklin Search". Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on January 10, 2024. Retrieved January 10, 2024.

- ^ Snow 1851, p. 192.

- ^ a b c Cyriax 1962, pp. 37–42.

- ^ a b Martin 2023, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Martin 2023, pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b Martin 2023, pp. 6–8.

- ^ Høvik & Jeremiassen 2023, pp. 977–978.

- ^ Martin 2022, pp. 247–248.

- ^ Martin 2023, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Snow 1851, p. 201.

- ^ Martin 2023, p. 13.

- ^ Høvik & Jeremiassen 2023, p. 992.

- ^ Martin 2022, pp. 247–249.

- ^ Martin 2022, pp. 240, 247–249.

- ^ a b c Høvik & Jeremiassen 2023, p. 998.

- ^ Høvik & Jeremiassen 2023, pp. 992–993.

- ^ Martin 2023, p. 7.

- ^ LeMoine & Darwent 2016, pp. 889–892.

- ^ a b Høvik & Jeremiassen 2023, p. 979.

- ^ Murray 1856, pp. 26–27.

- ^ "Qalasirssuaq (Erasmus Augustine Kallihirua), circa 1832/5–1856". Royal Museums Greenwich. Archived from the original on May 20, 2024. Retrieved May 20, 2024.

- ^ Høvik & Jeremiassen 2023, p. 981.

- ^ a b c Høvik & Jeremiassen 2023, p. 994.

- ^ Høvik & Jeremiassen 2023, p. 986.

- ^ Murray 1856, pp. 29–39.

- ^ Murray 1856, pp. 36–39.

- ^ Murray 1856, p. 45.

- ^ Murray 1856, pp. 45–47.

- ^ Murray 1856, p. 51.

- ^ Høvik & Jeremiassen 2023, pp. 978, 994.

- ^ Murray 1856, p. 4.

Bibliography

[edit]- Cyriax, R. J. (1962). "Adam Beck and the Franklin Search". The Mariner's Mirror. 48 (1): 35–51. doi:10.1080/00253359.1962.10657679.

- Høvik, Ingeborg; Jeremiassen, Axel (February 9, 2023). "Traces of an Arctic Voice: The Portrait of Qalaherriaq". Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies. 25 (7): 975–1003. doi:10.1080/1369801X.2023.2169626. hdl:10037/30303. Archived from the original on January 10, 2024. Retrieved January 10, 2024 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- LeMoine, Genevieve; Darwent, Christyann (2016). "Development of Polar Inughuit Culture in the Smith Sound Region". In Friesen, Max; Mason, Owen (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Prehistoric Arctic. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199766956.013.43. ISBN 9780199766956.

- Malaurie, Jean (2003). Ultima Thule: Explorers and Natives of the Polar North. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-05150-6.

- Martin, Peter R. (July 14, 2023). "'Kalli in the ship': Inughuit abduction and the shaping of Arctic knowledge". History and Anthropology: 1–26. doi:10.1080/02757206.2023.2235383.

- Martin, Peter R. (2022). "The Cartography of Kallihirua?: Reassessing Indigenous Mapmaking and Arctic Encounters". Cartographica. 57 (3): 247–249. doi:10.3138/cart-2021-0012. S2CID 253661275.

Primary sources

[edit]- Murray, Thomas Boyles (1856). Kalli, the Esquimaux Christian. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. Archived from the original on January 11, 2024. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- Snow, William Parker (1851). Voyage of the 'Prince Albert' in search of Sir John Franklin. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. ISBN 978-0-665-40695-9.

- 1830s births

- 1856 deaths

- Interpreters

- Inughuit people

- 19th-century translators

- 19th-century indigenous people of the Americas

- Alumni of St Augustine's College, Canterbury

- Greenlandic Christians

- Inuit drawing artists

- 19th-century deaths from tuberculosis

- Tuberculosis deaths in Newfoundland and Labrador

- Converts to Anglicanism

- Anglican missionaries in Canada

- Hunters

- 19th-century cartographers

- Cartographers of North America

- Greenlandic artists