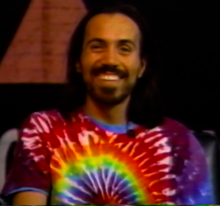

Ray Navarro

Ray Navarro | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Raymond Navarro November 6, 1964 |

| Died | November 9, 1990 (aged 26) New York City, New York, US |

| Education | Otis College of Art and Design (BFA) California Institute of the Arts (MFA) |

| Known for | HIV/AIDS activism Diva TV |

Raymond Robert Navarro (November 6, 1964 – November 9, 1990) was an American video artist, filmmaker, and HIV/AIDS activist. Navarro was an active member of ACT UP and a founder of Diva TV. His activism was featured in the documentary How to Survive a Plague. Navarro's art was exhibited at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, Tacoma Art Museum, Bronx Museum of the Arts, and Museum of Contemporary Art, Cleveland, among others. Navarro's papers, videos, and artworks are held at the ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries in Los Angeles.

Early life and education

[edit]Raymond Navarro was born in 1964 to Patricia Navarro.[1] He was raised in Simi Valley, California, and attended Otis Art Institute before graduating from the California Institute of the Arts.[2] He moved to New York City in 1988 to attend the Whitney Museum independent study program.[3] Navarro identified as a Mexican-American and a Chicano activist.[2]

Career

[edit]After moving to New York City, Navarro became an active member of ACT UP, an advocacy group working to impact the lives of people with AIDS.[3] He was one of nine founding members of Diva TV, which documented much of the work of ACT UP.[2] Activist Debra Levine called Navarro a "dazzling, outspoken, proudly queer ... Chicano-American AIDS activist".[4]

To protest the Roman Catholic Church's position on abortion rights, gay rights, and safe sex education, Navarro dressed as Jesus during an ACT UP event held on December 10, 1989, at Fifth Avenue and St. Patrick's Cathedral. The protest targeted Cardinal John O'Connor who promoted conservative[clarification needed] positions on sexual and public health issues in local and national political debates. At the event, Navarro interviewed demonstrators on the street. He protested with the chants: "We're here to say, we want to go to heaven, too!", and "Make sure your second coming is a safe one. Use condoms." The demonstration was included in the documentary Like a Prayer. In 2017, professor and author Anthony Michael Petro called Navarro the "camp superstar" of the documentary. Diva TV founder member Jean Carlomusto remarked in 2002 that Navarro's performance:

... was also really powerful because Ray, whose own illness was progressing very quickly, dressed as Jesus Christ that day outside was sort of leading chants outside of St. Pat's. And in his own way, as someone who had grown up Catholic, too, was sort of reclaiming this Christ figure as a revolutionary—use of Christ as someone saying, "Use condoms".[2]

In a 2014 "Revolution" issue of ART21 Magazine, film director Jim Hubbard stated that Navarro exuded "warmth and human connection. He had a great sense of political theater, a wonderful eye, and a mischievous smile that lit up the universe."[5]

In February 1990, Navarro presented an AIDS program at the CineFestival in San Antonio, Texas.[6]

After Navarro lost his vision due to cytomegalovirus retinitis, an AIDS-related complication, he and Zoe Leonard created a photographic series, Equipped. The series was a triptych of black-and-white photographs each showing a mobility device. Below each framed photograph, a plaque etched with a provocative phrase was displayed[3]—stud walk, hot butt, and third leg. Levine and Calkins believe that the piece is a type of self portrait of Navarro.[7][4] The frames are painted the same color as many prosthetic devices to reinforce the link between the device and the disabled body. Equipped addresses complexities of disease and its relation to race, sexuality, and class.[3] Levine wrote that the exhibit, "tantalizingly engages issues of sexual fetishism and desirability in disability".[4]

Navarro was one of the activists featured in the 2012 film How to Survive a Plague.[8]

Navarro's work was exhibited in the exhibition Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A. organized by ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives in collaboration with the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles for Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA in 2017. His work has also been displayed at Self Help Graphics & Art.[9]

Personal life

[edit]Navarro was dating Anthony Ledesma. Ledesma had been diagnosed with AIDS after becoming sick in 1988 or 1989. Navarro was diagnosed with AIDS in January 1990.[2] Before his death, Navarro had become deaf and blind.[8] He died in November 1990 at the age of 26.[2][1]

Legacy

[edit]Navarro's mother, Patricia speaks about her son's experiences. As of December 2009. she works to shape public policy related to HIV/AIDS and serves on the Ventura County Board of Supervisors HIV/AIDS Committee.[1] In memory of Navarro and Gerardo Velázquez, Harry Gamboa Jr. wrote the chapter "Light at the End of Tunnel Vision" for the 2018 book Latinx Writing Los Angeles: Nonfiction Dispatches from a Decolonial Rebellion.[10]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Mcgrath, Rachel (December 2, 2009). "County residents talk about their experiences living with HIV, AIDS". Ventura County Star. Retrieved 2020-10-21.

- ^ a b c d e f Petro, Anthony M. (December 2017). "Ray Navarro's Jesus Camp, AIDS Activist Video, and the "New Anti-Catholicism"". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 85 (4): 920–956. doi:10.1093/jaarel/lfx011. ISSN 0002-7189.

- ^ a b c d "Ray Navarro". Visual AIDS. Retrieved 2019-01-03.

- ^ a b c Levine, Debra (December 12, 2004). "Another Kind of Love: A Performance of Prosthetic Politics" (PDF). Hemispheric Institute of Performance & Politics. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- ^ Hubbard, Jim (December 1, 2014). "1989—What We Lost". Art21 Magazine. Retrieved 2019-01-03.

- ^ Palomares, Hortensia (February 1, 1990). "New York artist to present AIDS program". Austin American-Statesman. Retrieved 2019-01-03 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Calkins, Hannah (Fall 2014). "Art is Not Enough: The Artist's Body as Protest" (PDF). Gnovis. 15 (1).

- ^ a b Franke-Ruta, Garance (2013-02-24). "The Plague Years, in Film and Memory". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2019-01-03.

- ^ Durón, Maximilíano (January 2, 2018). "Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A." Artillery Magazine. Retrieved 2019-01-03.

- ^ Gamboa, Harry (2018), "Light at the End of Tunnel Vision", Latinx Writing Los Angeles, UNP - Nebraska, pp. 143–154, doi:10.2307/j.ctt21kk1rh.15, ISBN 9781496206176

External links

[edit]- Ray Navarro at IMDb

- 1964 births

- 1990 deaths

- American HIV/AIDS activists

- AIDS-related deaths in New York (state)

- 20th-century American artists

- American video artists

- LGBTQ Hispanic and Latino American people

- American artists of Mexican descent

- California Institute of the Arts alumni

- American film directors of Mexican descent

- Catholics from California

- LGBTQ people from California

- People from Simi Valley, California

- American gay artists

- Artists from California

- Members of ACT UP

- 20th-century American LGBTQ people