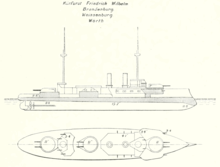

SMS Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm

An 1899 lithograph of SMS Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm |

| Namesake | Friedrich Wilhelm |

| Builder | Kaiserliche Werft Wilhelmshaven |

| Laid down | 1890 |

| Launched | 30 June 1891 |

| Commissioned | 29 April 1894 |

| Fate | Sold to the Ottoman Empire in 1910 |

| Name | Barbaros Hayreddin |

| Namesake | Hayreddin Barbarossa |

| Acquired | 12 September 1910 |

| Fate | Sunk by the British submarine HMS E11, 8 August 1915 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Brandenburg-class battleship |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 115.7 m (379 ft 7 in) loa |

| Beam | 19.5 m (64 ft) |

| Draft | 7.9 m (25 ft 11 in) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 16.5 knots (30.6 km/h; 19.0 mph) |

| Range | 4,300 nmi (8,000 km; 4,900 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement |

|

| Armament |

|

| Armor | |

SMS Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm ("His Majesty's Ship Prince-elector Friedrich Wilhelm")[a] was one of the first ocean-going battleships[b] of the German Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial Navy). The ship was named for Prince-elector (Kurfürst) Friedrich Wilhelm, 17th-century Duke of Prussia and Margrave of Brandenburg. She was the fourth pre-dreadnought of the Brandenburg class, along with her sister ships Brandenburg, Weissenburg, and Wörth. She was laid down in 1890 in the Imperial Dockyard in Wilhelmshaven, launched in 1891, and completed in 1893. The Brandenburg-class battleships carried six large-caliber guns in three twin turrets, as opposed to four guns in two turrets, as was the standard in other navies.

Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm served as the flagship of the Imperial fleet from her commissioning in 1894 until 1900. She saw limited active duty during her service career with the German fleet due to the relatively peaceful nature of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. As a result, her career focused on training exercises and goodwill visits to foreign ports. These training maneuvers were nevertheless very important to developing German naval tactical doctrine in the two decades before World War I, especially under the direction of Alfred von Tirpitz. She, along with her three sisters, saw only one major overseas deployment, to China in 1900–1901, during the Boxer Uprising. The ship underwent a major modernization in 1904–1905.

In 1910, Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm was sold to the Ottoman Empire and renamed Barbaros Hayreddin. She saw heavy service during the Balkan Wars, primarily providing artillery support to Ottoman ground forces in Thrace. She also took part in two naval engagements with the Greek Navy—the Battle of Elli in December 1912, and the Battle of Lemnos the following month. Both battles were defeats for the Ottoman Navy. In a state of severe disrepair, the old battleship was partially disarmed after the Ottoman Empire joined the Central Powers early in World War I. On 8 August 1915 the ship was torpedoed and sunk off the Dardanelles by the British submarine HMS E11 with heavy loss of life.

Description

[edit]

The four Brandenburg-class battleships were the first pre-dreadnought battleships of the Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial Navy).[1] Prior to the ascension of Kaiser Wilhelm II to the German throne in June 1888, the German fleet had been largely oriented toward defense of the German coastline and Leo von Caprivi, chief of the Reichsmarineamt (Imperial Naval Office), had ordered a number of coastal defense ships in the 1880s.[2] In August 1888, the Kaiser, who had a strong interest in naval matters, replaced Caprivi with Vizeadmiral (VAdm—Vice Admiral) Alexander von Monts and instructed him to include four battleships in the 1889–1890 naval budget. Monts, who favored a fleet of battleships over the coastal defense strategy emphasized by his predecessor, cancelled the last four coastal defense ships authorized under Caprivi and instead ordered four 10,000-metric-ton (9,800-long-ton; 11,000-short-ton) battleships. Though they were the first modern battleships built in Germany, presaging the Tirpitz-era High Seas Fleet, the authorization for the ships came as part of a construction program that reflected the strategic and tactical confusion of the 1880s caused by the Jeune École (Young School).[3]

Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm was 115.7 meters (379 ft 7 in) long overall, had a beam of 19.5 m (64 ft) which was increased to 19.74 m (64 ft 9 in) with the addition of torpedo nets, and had a draft of 7.6 m (24 ft 11 in) forward and 7.9 m (25 ft 11 in) aft. She displaced 10,013 t (9,855 long tons) as designed and up to 10,670 t (10,500 long tons) at full combat load. She was equipped with two sets of 3-cylinder vertical triple expansion steam engines that each drove a screw propeller. Steam was provided by twelve transverse cylindrical Scotch marine boilers. The ship's propulsion system was rated at 10,000 metric horsepower (9,900 ihp) and a top speed of 16.5 knots (30.6 km/h; 19.0 mph). She had a maximum range of 4,300 nautical miles (8,000 km; 4,900 mi) at a cruising speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). Her crew numbered 38 officers and 530 enlisted men.[1]

The ship was unusual for her time in that she possessed a broadside of six heavy guns in three twin gun turrets, rather than the four-gun main battery typical of contemporary battleships.[2] The forward and aft turrets carried 28-centimeter (11 in) K L/40 guns,[c] and the amidships turret mounted a pair of 28 cm guns with shorter L/35 barrels. Her secondary armament consisted of eight 10.5 cm (4.1 in) SK L/35 and eight 8.8 cm (3.5 in) SK L/30 quick-firing guns mounted in casemates. Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm's armament suite was rounded out with six 45 cm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes, all in above-water swivel mounts.[1]

Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm was protected with nickel-steel Krupp armor, a new type of stronger steel. Her main belt armor was 400 millimeters (15.7 in) thick in the central citadel that protected the ammunition magazines and machinery spaces. The deck was 60 mm (2.4 in) thick. The main battery barbettes were protected with 300 mm (11.8 in) thick armor.[1]

Service history

[edit]

In German service

[edit]Construction to 1895

[edit]Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm was the fourth and final ship of her class. She was ordered as battleship D,[1] and was laid down at the Kaiserliche Werft (Imperial Shipyard) in Wilhelmshaven in 1890. She was the first ship of the class to be launched, on 30 June 1891.[5] The ceremony was attended by Kaiser Wilhelm II and his wife, Augusta Victoria.[6] She was commissioned into the German fleet on 29 April 1894, the same day as her sister Brandenburg.[5] While on sea trials, the ship suffered from several problems with her propulsion system. She was therefore decommissioned for repairs to the machinery, before being recommissioned on 1 November 1894.[6] Construction of Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm cost the German navy 11.23 million marks.[7] Upon her commissioning, Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm was assigned to I Division of I Battle Squadron alongside her three sisters.[8] She replaced the ironclad Bayern as the Squadron flagship on 16 November, under the command of VAdm Hans von Koester. Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm would remain the flagship for the next six years.[6] I Division was accompanied by the four older Sachsen-class ironclads in II Division, though by 1901–1902, the Sachsens were replaced by the new Kaiser Friedrich III-class battleships.[9] The ship was a training ground for later commanders in chief of the High Seas Fleet, including Admirals Reinhard Scheer and Franz von Hipper, who both served aboard the ship as navigation officers during 1897 and October 1898 to September 1899, respectively.[10][11]

After entering active service, Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm and the rest of the squadron attended ceremonies for the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal at Kiel on 3 December 1894. The squadron thereafter began a winter training cruise in the Baltic Sea; this was the first such cruise by the German fleet. In previous years, the bulk of the fleet was deactivated for the winter months. During this voyage, I Division anchored in Stockholm from 7 to 11 December, during the 300th anniversary of the birth of Swedish king Gustavus Adolphus. King Oscar II held a reception for the visiting German delegation, which included Prince Heinrich, the younger brother of Wilhelm II and the commander of the battleship Wörth. Thereafter, further exercises were conducted in the Baltic before the ships had to put into their home ports for repairs. During this dockyard period, Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm had her funnels extended in height.[12]

1895 began with what became the normal trips to Heligoland and then to Bremerhaven, with Wilhelm II on board. This was followed by individual ship and divisional training, which was interrupted by a voyage to the northern North Sea. On this trip, Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm was accompanied by her sister ship Brandenburg; the two battleships stopped in Lerwick in Shetland from 16 to 23 March. This was the first time units of the main German fleet had left home waters. The purpose of the exercise was to test the ships in heavy weather; both vessels performed admirably. In May, more fleet maneuvers were carried out in the western Baltic, and they were concluded by a visit of the fleet to Kirkwall in Orkney. The squadron returned to Kiel in early June, where preparations were under way for the opening of the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal. Tactical exercises were carried out in Kiel Bay in the presence of foreign delegations to the opening ceremony.[13]

On 28 June, an explosion occurred on one of the ship's pinnaces killing seven crewmen and badly injuring the future VAdm Wilhelm Starke. Further training exercises lasted until 1 July, when I Division began a voyage into the Atlantic Ocean. This operation had political motives; Germany had only been able to send a small contingent of vessels—the protected cruiser Kaiserin Augusta, the coastal defense ship Hagen, and the screw frigate Stosch—to an international naval demonstration off the Moroccan coast at the same time. The main fleet could therefore provide moral support to the demonstration by steaming to Spanish waters. Rough weather again allowed Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm and her sister ships to demonstrate their excellent seakeeping. The fleet departed Vigo and stopped in Queenstown, Ireland. Wilhelm II, aboard his yacht Hohenzollern, attended the Cowes Regatta while the rest of the fleet stayed off the Isle of Wight.[14]

On 10 August, the fleet returned to Wilhelmshaven and began preparations for the autumn maneuvers later that month. The first exercises began in the Heligoland Bight on 25 August. The fleet then steamed through the Skagerrak to the Baltic; heavy storms caused significant damage to many of the ships and the torpedo boat S41 capsized and sank in the storms—only three men were saved. The fleet stayed briefly in Kiel before resuming exercises, including live-fire exercises, in the Kattegat and the Great Belt. The main maneuvers began on 7 September with a mock attack from Kiel toward the eastern Baltic. Subsequent maneuvers took place off the coast of Pomerania and in Danzig Bay. A fleet review for Wilhelm II off Jershöft concluded the maneuvers on 14 September. Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm went into drydock for periodic maintenance on 1 October. The ironclad Baden temporarily replaced her as flagship until the work was completed on 20 October. The rest of the year was spent on individual ship training, with the exception of a short trip to Gothenburg from 5 to 9 November. Only three other ships accompanied Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm on this visit: the ironclads Sachsen and Württemberg and the aviso Pfeil. On 9 December, the squadron commander shifted his flag to Württemberg while Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm went into drydock for an overhaul.[15]

1896–1900

[edit]

The year 1896 followed much the same pattern as the previous year. On 10 March 1896, Koester once again raised his flag aboard Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm. Individual ship training was conducted through April, followed by squadron training in the North Sea in late April and early May. This included a visit to the Dutch ports of Vlissingen and Nieuwediep. Further maneuvers, which lasted from the end of May to the end of July, took the squadron further north in the North Sea, frequently into Norwegian waters. The ships visited Bergen from 11 to 18 May. During the maneuvers, Wilhelm II and the Chinese viceroy Li Hongzhang observed a fleet review off Kiel. On 9 August, the training fleet assembled in Wilhelmshaven for the annual autumn fleet training. Following the conclusion of the maneuvers, Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm again went into dock for maintenance, and while she was out of service, Koester transferred his flag to Sachsen from 16 September to 3 October. Koester again flew his flag aboard Sachsen from 15 December to 1 March 1897.[16]

Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm and the rest of the fleet operated under the normal routine of individual and unit training in the first half of 1897. Early in the year, the naval command considered deploying I Division, including Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm, to another naval demonstration off Morocco to protest the murder of two German nationals there, but a smaller squadron of sailing frigates was sent instead. The typical routine was interrupted in early August when Wilhelm II and Augusta went to visit the Russian imperial court at Kronstadt; both divisions of I Squadron were sent to accompany the Kaiser. They had returned to Neufahrwasser in Danzig on 15 August, where the rest of the fleet joined them for the annual autumn maneuvers. These exercises reflected the tactical thinking of the new State Secretary of the Reichsmarineamt, Konteradmiral (KAdm—Rear Admiral) Alfred von Tirpitz, and the new commander of I Squadron, VAdm August von Thomsen. These new tactics stressed accurate gunnery, especially at longer ranges, though the necessities of the line-ahead formation led to a great deal of rigidity in the tactics. Thomsen's emphasis on shooting created the basis for the excellent German gunnery during World War I. The maneuvers were completed by 22 September in Wilhelmshaven.[17]

In early December, I Division conducted maneuvers in the Kattegat and the Skagerrak, though they were cut short due to shortages in officers and men. The fleet followed the typical routine of individual and fleet training in 1898 without incident, though a voyage to the British Isles was also included. The fleet stopped in Queenstown, Greenock, and Kirkwall. The fleet assembled in Kiel on 14 August for the annual autumn exercises. The maneuvers included a mock blockade of the coast of Mecklenburg and a pitched battle with an "Eastern Fleet" in the Danzig Bay. While steaming back to Kiel, a severe storm hit the fleet, causing significant damage to many ships and sinking the torpedo boat S58. The fleet then transited the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal and continued the maneuvers in the North Sea. Training finished on 17 September in Wilhelmshaven. In December, I Division conducted artillery and torpedo training in Eckernförde Bay, followed by divisional training in the Kattegat and Skagerrak. During these maneuvers, the division visited Kungsbacka, Sweden, from 9 to 13 December. After returning to Kiel, the ships of I Division went into dock for their winter repairs.[18]

On 5 April 1899, the ship participated in the celebrations commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Eckernförde during the First Schleswig War. In May, I and II Divisions, along with the Reserve Division from the Baltic, went on a major cruise into the Atlantic. On the voyage out, I Division stopped in Dover and II Division went into Falmouth to restock their coal supplies. I Division then joined II Division at Falmouth on 8 May, and the two units then departed for the Bay of Biscay, arriving at Lisbon on 12 May. There, they met the British Channel Fleet of eight battleships and four armored cruisers. The Portuguese king, Carlos I came aboard Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm to inspect the German flagship. The German fleet then departed for Germany, stopping again in Dover on 24 May. There, they participated in the naval review celebrating Queen Victoria's 80th birthday. The fleet returned to Kiel on 31 May.[19]

In July, the fleet conducted squadron maneuvers in the North Sea, which included coast defense exercises with soldiers from X Corps. On 16 August, the fleet assembled in Danzig once again for the annual autumn maneuvers. The exercises started in the Baltic and on 30 August the fleet passed through the Kattegat and Skagerrak and steamed into the North Sea for further maneuvers in the German Bight, which lasted until 7 September. The third phase of the maneuvers took place in the Kattegat and the Great Belt from 8 to 26 September, when the maneuvers concluded and the fleet went into port for annual maintenance. The year 1900 began with the usual routine of individual and divisional exercises. In the second half of March, the squadrons met in Kiel, followed by torpedo and gunnery practice in April and a voyage to the eastern Baltic. From 7 to 26 May, the fleet went on a major training cruise to the northern North Sea, which included stops in Shetland from 12 to 15 May and in Bergen from 18 to 22 May. On 8 July, the ships of I Division were reassigned to II Division, and the role of fleet flagship was transferred to the recently commissioned battleship Kaiser Wilhelm II.[20]

Boxer Uprising

[edit]Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm saw her first major operation in 1900, when I Division was deployed to China during the Boxer Uprising.[2] Chinese nationalists laid siege to the foreign embassies in Beijing and murdered the German minister.[21] At the time, the East Asia Squadron consisted of the protected cruisers Kaiserin Augusta, Hansa, Hertha, the small cruisers Irene, Gefion, and the gunboats Jaguar and Iltis,[22] but the Kaiser decided that an expeditionary force was necessary to reinforce the Eight Nation Alliance that had formed to defeat the Boxers. The expeditionary force consisted of Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm and her three sisters, six cruisers, 10 freighters, three torpedo boats, and six regiments of marines, under the command of Generalfeldmarschall (Field Marshal) Alfred von Waldersee.[23] Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm served as the flagship of KAdm Richard von Geißler, who took command on 6 July.[24]

On 7 July, Geißler reported that his ships were ready for the operation, and they left two days later. The four battleships and the aviso Hela transited the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal and stopped in Wilhelmshaven to rendezvous with the rest of the expeditionary force. On 11 July, the force steamed out of the Jade Bight, bound for China. They stopped to coal at Gibraltar on 17–18 July and they passed through the Suez Canal on 26–27 July. More coal was taken on at Perim in the Red Sea, and on 2 August, the fleet entered the Indian Ocean. On 10 August, the ships reached Colombo, Ceylon, and on 14 August they passed through the Strait of Malacca. They arrived in Singapore on 18 August and departed five days later, reaching Hong Kong on 28 August. Two days later, the expeditionary force stopped in the outer roadstead at Wusong, downriver from Shanghai. From there, Wörth was detached to cover the disembarkation of the German expeditionary corps outside the Taku Forts, while Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm and her other two sister ships joined the blockade of the Yangtze River, which also included a British contingent of two battleships, three cruisers, four gunboats, and one destroyer. A small Chinese fleet stationed upriver did not even clear their ships for action, owing to the strength of the Anglo-German fleet.[25]

By the time the German fleet had arrived, the siege of Beijing had already been lifted by forces from other members of the Eight-Nation Alliance that had formed to deal with the Boxers.[26] In early September, Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm and the rest of the German fleet was moved to the Yellow Sea, where Waldersee, who had been given command of all ground forces of the Eight-Nation Alliance, planned stronger actions against the harbors of northern China. On 3–4 September, the flagship of the East Asia Squadron, Fürst Bismarck reconnoitered the harbors of Shanhaiguan and Qinhuangdao. Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm then went to Shanhaiguan and sent a landing party of 100 men ashore while her torpedo crew cleared the Chinese minefields. She then returned to the Wusong roads while the ships of the East Asia Squadron remained off both ports. Since the situation had calmed, Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm and her sisters were sent to Hong Kong or Nagasaki, Japan in early 1901 for overhauls; Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm went to Nagasaki from 4 to 23 January. In March, the expeditionary fleet reassembled in Qingdao for gunnery and tactical exercises.[27]

On 26 May, the German high command recalled the expeditionary force to Germany. The fleet took on supplies in Shanghai and departed Chinese waters on 1 June. The fleet stopped in Singapore from 10 to 15 June and took on coal before proceeding to Colombo, where they stayed from 22 to 26 June. Steaming against the monsoons forced the fleet to stop in Mahé, Seychelles to take on more coal. The fleet then stopped for a day each to take on coal in Aden and Port Said. On 1 August they reached Cádiz, and then met with I Division and steamed back to Germany together. They separated after reaching Heligoland, and on 11 August after reaching the Jade roadstead, the ships of the expeditionary force were visited by Koester, who was now the Inspector General of the Navy. The following day, Geißler lowered his flag aboard Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm and the expeditionary fleet was dissolved.[28] In the end, the operation cost the German government more than 100 million marks.[29]

1901–1910

[edit]Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm went to Kiel after returning from the expedition to China, where on 14 August KAdm Fischel raised his flag aboard the ship. She was assigned to I Squadron as the second command flagship for the annual autumn maneuvers.[d] These exercises were interrupted by the visit from Nicholas II of Russia, who came aboard Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm. After the maneuvers, Fischel was replaced by KAdm Curt von Prittwitz und Gaffron on 24 October. In late 1901, the fleet went on a cruise to Norway, during which Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm stopped in Oslo. During the months of December, January, and February, the ship was in drydock for major repair work.[33]

The pattern of training for 1902 remained unchanged from previous years; I Squadron went on a major training cruise that started on 25 April. The squadron initially steamed to Norwegian waters, then rounded the northern tip of Scotland, and stopped in Irish waters. The ships returned to Kiel on 28 May. Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm then participated in the annual autumn maneuvers, after which she was decommissioned, with the new battleship Wittelsbach taking her place as second command flagship. The four Brandenburg class battleships were taken out of service for a major reconstruction.[33] The work to Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm was done at the Kaiserliche Werft shipyard in Wilhelmshaven.[1] The work included increasing the ship's coal storage capacity and adding a pair of 10.5 cm guns. The plans had initially called for the center 28 cm turret to be replaced with an armored battery of medium-caliber guns, but this proved to be prohibitively expensive. Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm was the last ship of her class to complete her reconstruction, which was finished on 14 December 1905.[34]

On 1 January 1906 she was assigned to II Squadron and served as the flagship of first KAdm Henning von Holtzendorff, and then during the autumn maneuvers of KAdm Adolf Paschen. The fleet conducted its normal routine of individual and unit training, interrupted only by a cruise to Norway from mid-July to early August. The annual autumn maneuvers occurred as usual. Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm served as the second command flagship in I Squadron of the newly created High Seas Fleet, but at the end of the 1906 training year, she was removed from active duty and her place was taken by the new battleship Pommern.[35]

Beginning on 1 October 1907, Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm was assigned to the Reserve Squadron in the North Sea, which had been created in early 1907 to train new crews. Her three sister ships joined her in this unit; their duties typically consisted of training cruises in the North Sea. From 5 to 25 April, she operated with the Training Squadron with its flagship Vineta. In September, the Reserve Squadron contributed vessels to the autumn maneuvers; Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm served as the Reserve Squadron flagship, with the coastal defense ships Ägir and Frithjof, the minelaying cruisers Nautilus and Albatross, and the old avisos Blitz, Pfeil, and Zieten. The Squadron was organized in Cuxhaven and joined the High Seas Fleet in the German Bight on 8 September. They participated in the main series of exercises off Heligoland, and the squadron was dissolved when the maneuvers ended on 12 September.[35]

After completing her annual winter overhaul, Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm returned to the Reserve Squadron in January 1909. Starting on 27 March, she operated with the Training Squadron again, the flagship of which was now the armored cruiser Friedrich Carl. Between 30 March and 24 April, she cruised in the central Baltic and in the waters around Rügen. She and the rest of the Reserve Squadron joined the autumn maneuvers in August and the battleship Schwaben replaced Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm as the flagship of the Reserve Squadron. Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm was then transferred to the VII Division in the Reserve Squadron. She continued in this routine in early 1910; she operated with the Training Squadron from 4 to 29 April and cruised in the Skagerrak and the western Baltic. The battleship was scheduled to take part in the autumn maneuvers, but shortly before the fleet assembled for the exercises, both she and Weissenburg were sold to the Ottoman Empire.[36]

In Ottoman service

[edit]In late 1909, the German military attache to the Ottoman Empire began a conversation with the Ottoman Navy about the possibility of selling German warships to the Ottomans to counter Greek naval expansion. After lengthy negotiations, including Ottoman attempts to buy one or more of the new battlecruisers Von der Tann, Moltke, and Goeben, the Germans offered to sell the four ships of the Brandenburg class at a cost of 10 million marks. The Ottomans chose to buy Kurfürst Friedrich Wilhelm and Weissenburg, since they were the more advanced ships of the class.[37] The two battleships were renamed after the famous 16th-century Ottoman admirals, Hayreddin Barbarossa and Turgut Reis.[38][39][40] They were transferred on 1 September 1910, and German crews took the ships to Constantinople, along with four new destroyers also purchased from Germany.[41] The Ottoman navy, however, had great difficulty equipping the Barbaros Hayreddin and Turgut Reis; the navy had to pull trained enlisted men from the rest of the fleet just to put together crews for them.[42] Both vessels suffered from condenser troubles after they entered Ottoman service, which reduced their speed to 8 to 10 knots (15 to 19 km/h; 9 to 12 mph).[41]

A year later, in September 1911, Italy declared war on the Ottoman Empire. The two battleships and the ancient central battery ironclad Mesudiye—which had been built in the mid-1870s—had been on a summer training cruise since July, and so were prepared for the conflict.[40] On 1 October, shortly after the outbreak of war, Barbaros Hayreddin and the rest of the Ottoman fleet was moored at Beirut. The following day, the fleet departed for Constantinople for repairs in preparation to engage the Italian fleet.[43] Nevertheless, the bulk of the Ottoman fleet, including Barbaros Hayreddin, remained in port for the duration of the war.[40] By the end of the war, Barbaros Hayreddin and her sister were in very poor condition. Their rangefinders and the ammunition hoists for their main battery guns had been removed, their telephones did not work, and the pipes for their pumps were badly rusted. Most of the watertight doors could not close, and the condensers remained problematic.[44]

Balkan Wars

[edit]The First Balkan War broke out in October 1912, when the Balkan League attacked the Ottoman Empire after the war with Italy had revealed the scale of Ottoman weakness. The condition of Barbaros Hayreddin, as with most ships of the Ottoman fleet, had deteriorated significantly. During the war, Barbaros Hayreddin conducted gunnery training along with the other capital ships of the Ottoman navy, escorted troop convoys, and bombarded coastal installations.[39] On 17 October, Barbaros Hayreddin and Turgut Reis steamed to İğneada. Two days later, the two battleships bombarded Bulgarian artillery positions near Varna. On 30 October, Barbaros Hayreddin was back outside Varna to blockade the port along with the destroyer Nümune-i Hamiyet.[44] On 17 November, Barbaros Hayreddin and Mesudiye bombarded Bulgarian positions in support of I Corps, with the aid of artillery observers ashore.[45] The battleships' gunnery was poor, though it provided a morale boost for the defending Ottoman army dug in at Çatalca.[46] From 15 to 20 November, the ship was stationed at Büyükçekmece along with her sister ship and several other warships, but they saw no action against the small Bulgarian navy.[47]

In December 1912, the Ottoman fleet was reorganized into an armored division, which included Barbaros Hayreddin as flagship, two destroyer divisions, and a fourth division composed of warships intended for independent operations.[48] Over the next two months, the armored division attempted to break the Greek naval blockade of the Dardanelles, which resulted in two major naval engagements.[49]

Battle of Elli

[edit]

At the Battle of Elli on 16 December 1912, the Ottomans attempted to launch an attack on Imbros.[50] The Ottoman fleet sortied from the Dardanelles at 9:30; the smaller craft remained at the mouth of the straits while the battleships sailed north, hugging the coast. The Greek flotilla, which included the armored cruiser Georgios Averof and three Hydra-class ironclads, sailing from the island of Lemnos, altered course to the northeast to block the advance of the Ottoman battleships.[51] The Ottoman ships opened fire on the Greeks at 9:40, from a range of about 15,000 yd (14,000 m). Five minutes later, Georgios Averof crossed over to the other side of the Ottoman fleet, placing the Ottomans in the unfavorable position of being under fire from both sides. At 9:50 and under heavy pressure from the Greek fleet, the Ottoman ships completed a 16-point turn, which reversed their course, and headed for the safety of the straits. The turn was poorly conducted, and the ships fell out of formation, blocking each other's fields of fire.[50]

By 10:17, both sides had ceased firing and the Ottoman fleet withdrew into the Dardanelles. The ships reached port by 13:00 and transferred their casualties to the hospital ship Resit Paşa.[50] The battle was considered a Greek victory, because the Ottoman fleet remained blockaded.[49] During the battle, Barbaros Hayreddin was hit twice. The first shell struck the afterdeck and killed five men assigned to a damage control party. The second shell jammed the rear turret, placing it out of action. Shell fragments from this hit damaged several boilers and caused a fire in one of the coal bunkers.[50]

On 4 January 1913, the Ottoman Navy and Army attempted a landing at Bozca Ada (Tenedos) to retake the island from the Greeks. Barbaros Hayreddin and the rest of the fleet supported the operation, but the appearance of the Greek fleet forced the Ottomans to break off the operation. The Greeks also withdrew, and several Ottoman cruisers opened fire as both sides departed, but no damage was done. By 15:30, Barbaros Hayreddin was back at Çanakkale inside the safety of the Dardanelles. On 10 January, the fleet conducted a patrol outside the Dardanelles. They encountered several Greek destroyers and forced them to withdraw, but inflicted no damage on the Greek ships.[52]

Battle of Lemnos

[edit]

The Battle of Lemnos resulted from an Ottoman plan to lure the faster Georgios Averof away from the Dardanelles. The protected cruiser Hamidiye evaded the Greek blockade and broke out into the Aegean Sea in an attempt to draw the Greek cruiser into pursuit. Despite the threat posed by the cruiser, the Greek commander refused to detach Georgios Averof.[51] By mid-January, however, the Ottomans had learned that Georgios Averof remained with the Greek fleet, and so Kalyon Kaptanı (Captain) Ramiz Numan Bey, the Ottoman fleet commander, decided to attack the Greeks regardless.[52]

Barbaros Hayreddin, Turgut Reis, and other units of the Ottoman fleet departed the Dardanelles at 8:20 on the morning of 18 January, and sailed toward the island of Lemnos at a speed of 11 knots (20 km/h; 13 mph). Barbaros Hayreddin led the line of battleships, with a flotilla of torpedo boats on either side of the formation.[52] Georgios Averof, with the three Hydra-class ironclads and five destroyers trailing behind, intercepted the Ottoman fleet approximately 12 nautical miles (22 km; 14 mi) from Lemnos.[51] At 10:55, the Ottoman cruiser Mecidiye spotted the Greeks, and the fleet turned south to engage them.[52]

A long range artillery duel that lasted for two hours began at around 11:55, when the Ottoman fleet opened fire at a range of 8,000 m (26,000 ft). They concentrated their fire on the Greek Georgios Averof, which returned fire at 12:00. At 12:50, the Greeks attempted to cross the T of the Ottoman fleet, but Barbaros Hayreddin turned north to block the Greek maneuver. The Ottoman commander detached Mesudiye after a serious hit at 12:55. At around the same time, a shell hit Barbaros Hayreddin on her amidships turret, killing the entire gun crew. She was thereafter hit several times in the superstructure; these hits did relatively little damage, but they created significant smoke that was sucked into the boiler rooms and caused the ship's speed to fall to 5 knots (9.3 km/h; 5.8 mph). As a result, Turgut Reis took the lead of the formation and Bey decided to break off the engagement.[53]

Toward the end of the engagement, Georgios Averof closed to within 5,000 yd (4,600 m) and scored several hits on the fleeing Ottoman ships.[51] At 14:00, the Ottoman warships had come close enough to the shore to be protected by coastal batteries, forcing the Greeks to withdraw and ending the battle.[54] During the battle, both Barbaros Hayreddin and her sister had a barbette disabled by gunfire, and both caught fire as a result. Between Barbaros Hayreddin and Turgut Reis, the ships fired some 800 rounds, mostly of their main battery 28 cm (11 in) ammunition but without success.[55]

Subsequent operations

[edit]On 8 February 1913, the Ottoman navy supported an amphibious assault at Şarköy. Barbaros Hayreddin and Turgut Reis, along with several cruisers weighed anchor at 5:50 and arrived off the island at around 9:00.[47] The Ottoman fleet provided artillery support, from about a kilometer off shore.[56] The ships supported the left flank of the Ottoman army once it was ashore. The Bulgarian army provided stiff resistance that ultimately forced the Ottoman army to withdraw, though the withdrawal was successful in large part due to the gunfire support from Barbaros Hayreddin and the rest of the fleet. During the battle, Barbaros Hayreddin fired 250 rounds from her 10.5 cm (4.1 in) SK L/35 guns and 180 shells from her 8.8 cm (3.5 in) SK L/30 guns.[57]

In March 1913, the ship returned to the Black Sea to resume support of the Çatalca garrison, which was under renewed attacks by the Bulgarian army. On 26 March, the 28 cm (11 in) and 10.5 cm (4.1 in) shells fired by Barbaros Hayreddin and Turgut Reis helped to turn back the advance of the 2nd Brigade of the Bulgarian 1st Infantry Division.[58] On 30 March, the left wing of the Ottoman line turned to pursue the retreating Bulgarians. Their advance was supported by both field artillery and the heavy guns of Barbaros Hayreddin; the assault gained the Ottomans about 1,500 m (1,600 yd) by nightfall. In response, the Bulgarians brought the 1st Brigade to the front, which beat the Ottoman advance back to its starting position.[59]

World War I

[edit]

In the summer of 1914, World War I broke out in Europe, though the Ottomans initially remained neutral. On 3 August 1914, Barbaros Hayreddin began a refit at Constantinople—German engineers inspected her and other Ottoman warships in the dockyard and found them to be in a state of severe disrepair. Owing to the state of tension, repairs could not be effected, and only ammunition, coal, and other supplies were loaded.[60] By early November, the actions of the German battlecruiser Goeben, which had been transferred to the Ottoman Navy, resulted in declarations of war by Russia, France, and Great Britain.[61] Between 1914–1915, some of the ship's guns were removed and employed as coastal guns to shore up the defenses protecting the Dardanelles.[55] In the meantime, she was used as a floating artillery battery at the Nara naval base, along with her sister Turgut Reis. Early during this stint, the ships were immobilized, but as the threat from British submarines grew, steam was kept up in their boilers to allow them to move quickly.[62]

Barbaros Hayreddin returned to Constantinople on 11 March 1915; the Ottoman high command had decided that both ships were not needed at all times. Over the next several months, the two ships alternated trips to Constantinople. On 25 April, the two battleships bombarded the British landings on the first day of the Gallipoli Campaign. After firing fourteen shells, the fifteenth detonated in the right gun barrel in the center turret, destroying the gun. After a shell exploded inside one of Turgut Reis's guns in early June, both battleships were withdrawn. On 7 August, the British landed more troops at Suvla Bay, prompting the high command to send Barbaros Hayreddin to support the Ottoman defenses there. In addition, she was loaded with a large quantity of ammunition to resupply the Fifth Army fighting in the Gallipoli Campaign.[63] The next day, while she was en route to the area with only a single torpedo boat as escort, she was intercepted by the British submarine HMS E11[64] off Bolayır in the Sea of Marmara.[55] The submarine hit Barbaros Hayreddin with a single torpedo;[2] she capsized seven minutes later, but remained afloat for a few minutes before she slipped below the waves. The ship sank with the loss of 21 officers and 237 men. The rest of the crew were picked up by her escort and a second torpedo boat patrolling the area.[60]

Footnotes

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "SMS" stands for "Seiner Majestät Schiff", or "His Majesty's Ship" in German.

- ^ At the time she was laid down, the German navy referred to the ship as an "armored ship" (Panzerschiffe in German), instead of "battleship" (Schlachtschiff).[1]

- ^ In Imperial German Navy gun nomenclature, "K" stands for Kanone (cannon), while the L/40 denotes the length of the gun. In this case, the L/40 gun is 40 caliber, meaning that the length of the gun barrel is 40 times the bore diameter.[4]

- ^ The German Navy typically organized its battleships in eight-ship squadrons,[30] subdivided into two 4-ship divisions, each of which had its own flagship. The flagship for the first division also served as the squadron flagship, while the flagship for the second division served as the second command flagship.[31][32]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Gröner, p. 13.

- ^ a b c d Hore, p. 66.

- ^ Sondhaus Weltpolitik, pp. 179–181.

- ^ Grießmer, p. 177.

- ^ a b Lyon, p. 247.

- ^ a b c Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 174.

- ^ Weir, p. 23.

- ^ Campbell & Sieche, p. 141.

- ^ Herwig, p. 45.

- ^ Sweetman, p. 401.

- ^ Philbin, p. 94.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 175.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 175–176.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 75, 176.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 176–178.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 181–183.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 183.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 183–186.

- ^ Holborn, p. 311.

- ^ Perry, p. 28.

- ^ Herwig, p. 106.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 186.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 186–187.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 187.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 188–189.

- ^ Herwig, p. 103.

- ^ Campbell & Sieche, p. 135.

- ^ Gröner, p. xii.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 41.

- ^ a b Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 189.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 189–190.

- ^ a b Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 190.

- ^ Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Langensiepen & Güleryüz, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Gröner, p. 14.

- ^ a b Erickson, p. 131.

- ^ a b Langensiepen & Güleryüz, p. 17.

- ^ Childs, p. 24.

- ^ Langensiepen & Güleryüz, p. 15.

- ^ a b Langensiepen & Güleryüz, p. 20.

- ^ Hall, p. 36.

- ^ Erickson, p. 133.

- ^ a b Langensiepen & Güleryüz, p. 25.

- ^ Langensiepen & Güleryüz, p. 21.

- ^ a b Hall, pp. 64–65.

- ^ a b c d Langensiepen & Güleryüz, p. 22.

- ^ a b c d Fotakis, p. 50.

- ^ a b c d Langensiepen & Güleryüz, p. 23.

- ^ Langensiepen & Güleryüz, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Langensiepen & Güleryüz, p. 24.

- ^ a b c Mach, p. 390.

- ^ Erickson, p. 264.

- ^ Erickson, p. 270.

- ^ Erickson, p. 288.

- ^ Erickson, p. 289.

- ^ a b Langensiepen & Güleryüz, p. 28.

- ^ Staff, p. 19.

- ^ Langensiepen & Güleryüz, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Langensiepen & Güleryüz, p. 33.

- ^ Halpern, p. 119.

References

[edit]- Campbell, N. J. M. & Sieche, Erwin (1986). "Germany". In Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 134–189. ISBN 978-0-85177-245-5.

- Childs, Timothy (1990). Italo-Turkish Diplomacy and the War Over Libya, 1911–1912. New York: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09025-5.

- Erickson, Edward J. (2003). Defeat in Detail: The Ottoman Army in the Balkans, 1912–1913. Westport: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-97888-4.

- Fotakis, Zisis (2005). Greek naval strategy and policy, 1910–1919. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35014-3.

- Grießmer, Axel (1999). Die Linienschiffe der Kaiserlichen Marine: 1906–1918; Konstruktionen zwischen Rüstungskonkurrenz und Flottengesetz [The Battleships of the Imperial Navy: 1906–1918; Constructions between Arms Competition and Fleet Laws] (in German). Bonn: Bernard & Graefe Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7637-5985-9.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Hall, Richard C. (2000). The Balkan Wars, 1912–1913: prelude to the First World War. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-22946-3.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-352-7.

- Herwig, Holger (1998) [1980]. "Luxury" Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Amherst: Humanity Books. ISBN 978-1-57392-286-9.

- Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert & Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe: Biographien – ein Spiegel der Marinegeschichte von 1815 bis zur Gegenwart [The German Warships: Biographies − A Reflection of Naval History from 1815 to the Present] (in German). Vol. 5. Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7822-0456-9.

- Holborn, Hajo (1982). A History of Modern Germany: 1840–1945. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00797-7.

- Hore, Peter (2006). The Ironclads: An Illustrated History of Battleships From 1860 to the First World War. London: Southwater Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84476-299-6.

- Langensiepen, Bernd & Güleryüz, Ahmet (1995). The Ottoman Steam Navy 1828–1923. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-610-1.

- Lyon, Hugh (1979). "Germany". In Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger; Kolesnik, Eugene M. (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Greenwich: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Mach, Andrzej V. (1985). "Turkey". In Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal (eds.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. pp. 387–394. ISBN 978-0-87021-907-8.

- Perry, Michael (2001). Peking 1900: the Boxer rebellion. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-181-7.

- Philbin, Tobias R. III (1982). Admiral Hipper: The Inconvenient Hero. Amsterdam: B.R. Grüner. ISBN 978-90-6032-200-0.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (1997). Preparing for Weltpolitik: German Sea Power Before the Tirpitz Era. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-745-7.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (2001). Naval Warfare, 1815–1914. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-21478-0.

- Staff, Gary (2006). German Battlecruisers: 1914–1918. Oxford: Osprey Books. ISBN 978-1-84603-009-3.

- Sweetman, Jack (1997). The Great Admirals: Command at Sea, 1587–1945. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-229-1.

- Weir, Gary E. (1992). Building the Kaiser's Navy: The Imperial Navy Office and German Industry in the Tirpitz Era, 1890–1919. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-929-1.

Further reading

[edit]- Koop, Gerhard & Schmolke, Klaus-Peter (2001). Die Panzer- und Linienschiffe der Brandenburg-, Kaiser Friedrich III-, Wittlesbach-, Braunschweig- und Deutschland-Klasse [The Armored and Battleships of the Brandenburg, Kaiser Friedrich III, Wittelsbach, Braunschweig, and Deutschland Classes] (in German). Bonn: Bernard & Graefe Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7637-6211-8.

- Nottelmann, Dirk (2002). Die Brandenburg-Klasse: Höhepunkt des deutschen Panzerschiffbaus [The Brandenburg Class: High Point of German Armored Ship Construction] (in German). Hamburg: Mittler. ISBN 978-3-8132-0740-8.

- Weir, Gary E. (1992). Building the Kaiser's Navy: The Imperial Navy Office and German Industry in the Tirpitz Era, 1890–1919. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-929-1.

External links

[edit]- Barbaros Hayreddin, in Turkey in the First World War web site.