Sheikhdom of Kuwait

Sheikhdom of Kuwait | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1752–1961 | |||||||||

Flag

(1940–1961) Coat of Arms

(1956–1961) | |||||||||

| Anthem: Al-Salam al-Emiri "Emiri Salute" (Arabic: السلام الأميري) | |||||||||

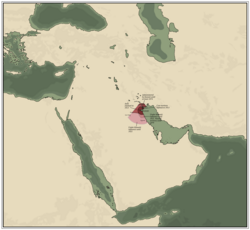

Territorial evolution of Kuwait | |||||||||

| Status | Vassal of The Ottoman Empire (1871–1899)[1][2] British Protectorate (1899–1961) | ||||||||

| Capital | Kuwait City | ||||||||

| Common languages | Kuwaiti Arabic Kuwaiti Persian | ||||||||

| Religion | Islam Christianity, Judaism | ||||||||

| Government | Absolute[citation needed] sheikhdom | ||||||||

| Sheikh | |||||||||

• 1752–1776 | Sabah I bin Jaber (first) | ||||||||

• 1950–1961 | Abdullah al-Salim al-Sabah (last) | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Independence from Bani Khalid | 1752 | ||||||||

| 23 July 1783 | |||||||||

| 5 May 1871 | |||||||||

| 23 January 1899 | |||||||||

| 17 December 1900 | |||||||||

| 29 July 1913 | |||||||||

| 18 May 1920 | |||||||||

| 10 October 1920 | |||||||||

| 28 January 1928 | |||||||||

• Independence from the United Kingdom | 19 June 1961 | ||||||||

| Currency | Dirham, gold dinar Rupee Gulf rupee (1959–61) | ||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | KW | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Kuwait | ||||||||

The Sheikhdom of Kuwait (Arabic: مشيخة الكويت, romanized: Mashīkhat al-Kuwayt) was a sheikhdom from 1752 to 1961. The sheikhdom became a British protectorate between 1899 and 1961 following the Anglo-Kuwaiti agreement of 1899. This agreement was made between Sheikh Mubarak Al-Sabah and the British Government in India, primarily as a defensive measure against threats from the Ottoman Empire. After 1961, the sheikdom became the state of Kuwait.

Foundation

[edit]Early settlement

[edit]In the early to mid 1700s, Kuwait was a small fishing village known as Grane (Kureyn). The region originally came under the rule of the Bani Khalid Emirate in 1670 after the expulsion of the Ottomans from Eastern Arabia (Lahsa Eyalet) by Barrack bin Ghurayr, Emir of the Bani Khalid, who successfully besieged the Ottoman governor Umar Pasha who surrendered and gave up his rule as the fourth Ottoman governor of al-Hasa.[3][4][5] After Al-Hasa Expedition 1871 Kuwait become nominal vassal of the Ottoman Empire in 1875 and was included in the Basra Vilayet.[6]

The families of the Bani Utbah arrived in Kuwait sometime in the mid-1700s and settled after receiving permission from the Emir of Bani Khalid Sa'dun bin Muhammad. The Utubs did not immediately settle in Kuwait, however, roaming for half a century before finally settling in Kuwait. They first left the region of central Arabia and settled in what is now Qatar. After a quarrel between them and some inhabitants of the region, they departed and settled near Umm Qasr in December 1701, living as brigands, raiding passing caravans and levying taxes over the shipping of the Shatt al-Arab.[7] Due to these practices, they were driven out of the area by the Ottoman Mutasallim of Basra and later lived in Sabiyya, an area bordering the north of Kuwait Bay, until finally requesting permission from the Bani Khalid to settle in Kuwait.[8]

The head of each family in the village of Kuwait gathered and chose Sabah I bin Jaber as the Sheikh of Kuwait, a governor of sorts under the Emir of Al Hasa. During this time as well, the power in governance was split between the Al Sabah, Al Khalifa, and Al Jalahma families in which the Al Sabah will have control over the reins of power whereas the Al Khalifa were in charge of trade and the flow of money, and the Jalahma would be in charge over work in the sea.

Sometime in the 1750s, the sheikdom of Kuwait emerged after an agreement between the Sheikh of Kuwait and the Emir of Bani Khalid in which Al Hasa recognised Sabah I bin Jaber's independent rule over Kuwait and in exchange Kuwait would not ally itself or support the enemies of Bani Khalid or interfere in the internal affairs of Bani Khalid in any way.

Economic growth

[edit]

After the arrival of the Bani Utbah, Kuwait gradually became a principal commercial centre for the transit of goods between India, Muscat, Baghdad, Persia, and Arabia.[9][10] By the late-1700s, Kuwait had already established itself as a trading route from the Persian Gulf to Aleppo.[11]

During the Persian siege of Basra in 1775–1779, Iraqi merchants took refuge in Kuwait and were partly instrumental in the expansion of Kuwait's boatbuilding and trading activities.[12] As a result, Kuwait's maritime commerce boomed.[12] Between the years 1775 and 1779, the Indian trade routes with Baghdad, Aleppo, Smyrna and Constantinople were diverted to Kuwait.[11] The English Factory was diverted to Kuwait in 1792, which consequently expanded Kuwait's resources beyond fishing and pearling.[11] The English Factory secured the sea routes between Kuwait, India and the east coasts of Africa.[11] This allowed Kuwaiti vessels to venture all the way to the pearling banks of Sri Lanka and trade goods with India and East Africa.[11] Kuwait was also the center for all caravans carrying goods between Basra, Baghdad and Aleppo during 1775–1779.[13]

Kuwait's strategic location and regional geopolitical turbulence helped foster economic prosperity in Kuwait in the second half of the 18th century.[14] Kuwait became wealthy due to Basra's instability in the late 18th century.[13] In the late 18th century, Kuwait partly functioned as a haven for Basra's merchants fleeing Ottoman government persecution.[15] Economic prosperity in the late 18th century attracted many immigrants from Iran and Iraq to Kuwait.[11] By 1800, it was estimated that Kuwait's sea trade reached 16 million Bombay rupees, a substantial amount at that time.[11] Kuwait's pre-oil population was ethnically diverse.[16] The population consisted of Arabs, Persians, Africans, Jews and Armenians.

Kuwait was the center of boat building in the Persian Gulf region in the nineteenth century until the early twentieth century.[17] Ship vessels made in Kuwait carried the bulk of international trade between the trade ports of India, East Africa, and Red Sea.[18][19][20] Boats made in Kuwait were capable of sailing up to China.[21] Kuwaiti ship vessels were renowned throughout the Indian Ocean for quality and design.[21][22] Kuwaitis also developed a reputation as the best sailors in the Persian Gulf.[23]

Kuwait was divided into three areas: Sharq, Jibla and Mirqab.[24] Sharq and Jibla were the most populated areas.[24] Sharq was mostly inhabited by Persians (Ajam).[24] Jibla was inhabited by immigrants from Saudi Arabia, Iraq and Bahrain.[24] Mirgab was lightly populated by butchers.

Kuwait was a central part of the trade in frankincense from Oman, textiles from China, and Indian spices, all destined for lucrative European markets.[25] Kuwait was also significant in the horse trade,[26] horses were regularly shipped by the way of sailing boats from Kuwait.[26] In the mid 19th century, it was estimated that Kuwait was exporting an average of 800 horses to India annually.[14]

Assassination of Muhammad Bin Sabah

[edit]In the 1870s, Ottoman officials were reasserting their presence in the Persian Gulf, with a military intervention in 1871—which was not effectively pursued—where family rivalries in Kuwait were breeding chaos.[1] The Ottomans were bankrupt and when the European banks took control of the Ottoman budget in 1881, additional income was required from Kuwait. Midhat Pasha, the governor of Iraq, demanded that Kuwait submit financially to Ottoman rule. The al-Sabah found diplomatic allies in the British Foreign Office. However, under Abdullah II Al-Sabah, Kuwait pursued a general pro-Ottoman foreign policy, formally taking the title of Ottoman provincial governor, this relationship with the Ottoman Empire did result in Ottoman interference with Kuwaiti laws and selection or rulers.[2]

In May 1896, Shaikh Muhammad Al-Sabah was assassinated by his half-brother, Mubarak, who, in early 1897, was recognized, by the Ottoman sultan, as the qaimmaqam (provincial sub-governor) of Kuwait.[1]

Mubarak the Great

[edit]

Mubarak's seizure of the throne via murder left his brother's former allies as a threat to his rule, especially as his opponents gained the backing of the Ottomans.[2] In July, Mubarak invited the British to deploy gunboats along the Kuwaiti coast. Britain saw Mubarak's desire for an alliance as an opportunity to counteract German influence in the region and so agreed.[2] This led to what is known as the First Kuwaiti Crisis, in which the Ottomans demanded that the British stop interfering within what they believed to be was their sphere of influence. In the end, the Ottoman Empire backed down, rather than go to war.

In January 1899, Mubarak signed an agreement with the British which pledged that Kuwait would never cede any territory nor receive agents or representatives of any foreign power without the British Government's consent. In essence, this policy gave Britain control of Kuwait's foreign policy.[2] The treaty also gave Britain responsibility for Kuwait's national security. In return, Britain agreed to grant an annual subsidy of 15,000 Indian rupees (£1,500) to the ruling family. In 1910, Mubarak raised taxes. Therefore, three wealthy business men Ibrahim Al-Mudhaf, Helal Al-Mutairi, and Shamlan Ali bin Saif Al-Roumi (brother of Hussain Ali bin Saif Al-Roumi), led a protest against Mubarak by making Bahrain their main trade point, which negatively affected the Kuwaiti economy. However, Mubarak went to Bahrain and apologised for raising taxes and the three business men returned to Kuwait. In 1915, Mubarak the Great died and was succeeded by his son Jaber II Al-Sabah, who reigned for just over one year until his death in early 1917. His brother Sheikh Salim Al-Mubarak Al-Sabah succeeded him.

Under the rule of Mubarak, Kuwait was dubbed the "Marseille of the Gulf" because its economic vitality attracted a large variety of people.[27] In a good year, Kuwait's annual revenue actually came up to 100,000 riyals,[15] the governor of Basra considered Kuwait's annual revenue an astounding figure.[15] A Western author's account of Kuwait in 1905:[28]

Kuwait was the Marseilles of the Persian Gulf. Its population was good natured, mixed, and vicious. As it was the outlet from the north to the Gulf and hence to the Indies, merchants from Bombay and Tehran, Indians, Persians, Syrians from Aleppo and Damascus, Armenians, Turks and Jews, traders from all the East, and some Europeans came to Kuwait. From Kuwait, the caravans set out for Central Arabia and for Syria. H. C. Armstrong, Lord of Arabia[28]

Anglo-Ottoman convention

[edit]

Despite the Kuwaiti government's desire to either be independent or under British protection, in the Anglo-Ottoman Convention of 1913, the British concurred with the Ottoman Empire in defining Kuwait as an autonomous kaza of the Ottoman Empire and that the Sheikhs of Kuwait were independent leaders as well as kaymakams (provincial sub-governors) of the Ottoman government.

The independence of Kuwait was also highlighted by the statement made by Sheikh Mubarak Al-Sabah to the German team who requested an audience with him over the extension of the Berlin–Baghdad railway to Kuwait. Mubarak said he would not sell or rent any piece of his land to a foreigner and that he did not acknowledge the authority of the Ottomans over Kuwait.[29]

The convention ruled that Sheikh Mubarak had independent authority over an area extending out to a radius of 80 kilometres (50 mi) from the capital. This region was marked by a red circle and included the islands of Auhah, Bubiyan, Failaka, Kubbar, Mashyan, and Warba. A green circle designated an area extending out an additional 100 kilometres (62 mi) in radius, within which the kaymakam was authorised to collect tribute and taxes from the natives.

History as a Protected State of Britain

[edit]Collapse of economy

[edit]

In the first decades of the twentieth century, Kuwait had a well-established elite: wealthy trading families who were linked by marriage and shared economic interests.[30] The elite were long-settled, urban, Sunni families, the majority of which claim descent from the original 30 Bani Utubi families.[30] The wealthiest families were trade merchants who acquired their wealth from long-distance commerce, shipbuilding and pearling.[30] They were a cosmopolitan elite, they traveled extensively to India, Africa and Europe.[30] The elite educated their sons abroad more than other Gulf Arab elite.[30] Western visitors noted that Kuwait's elite used European office systems, typewriters and followed European culture with curiosity.[30] The richest families were involved in general trade.[30] The merchant families of Al-Ghanim and Al-Hamad were estimated to be worth millions before the 1940s.[30]

However, Kuwait immensely declined in regional economic importance,[21] mainly due to many trade blockades and the world economic depression.[31] Before Mary Bruins Allison visited Kuwait in 1934, Kuwait lost its prominence in long-distance trade.[21] During World War I, the British Empire imposed a trade blockade against Kuwait because Kuwait's ruler (Salim Al-Mubarak Al-Sabah) supported the Ottoman Empire, who was in the Central Powers.[31][32][33] The British economic blockade heavily damaged Kuwait's economy.[33]

The Great Depression negatively impacted Kuwait's economy starting in the late 1920s.[34] International trading was one of Kuwait's main sources of income before oil.[34] Kuwaiti merchants were mostly intermediary merchants.[34] As a result of European decline of demand for goods from India and Africa, the economy of Kuwait suffered. The decline in international trade resulted in an increase in gold smuggling by Kuwaiti ships to India.[34] Some Kuwaiti merchant families became rich due to gold smuggling to India.[35]

Kuwait's pearling industry also collapsed as a result of the worldwide economic depression.[35] At its height, Kuwait's pearling industry led the world's luxury market, regularly sending out between 750 and 800 ship vessels to meet the European elite's need for luxuries pearls.[35] During the economic depression, luxuries like pearls were in little demand.[35] The Japanese invention of cultured pearls also contributed to the collapse of Kuwait's pearling industry.[35]

Following the Kuwait–Najd War of 1919–1920, Ibn Saud imposed a tight trade blockade against Kuwait from the years 1923 until 1937.[31][34] The goal of the Saudi economic and military attacks on Kuwait was to annex as much of Kuwait's territory as possible.[31] At the Uqair conference in 1922, the boundaries of Kuwait and Najd were set.[31] Kuwait had no representative at the Uqair conference.[31] After the Uqair conference, Kuwait was still subjected to a Saudi economic blockade and intermittent Saudi raiding.[31]

In 1937, Freya Stark wrote about the extent of poverty in Kuwait at the time:[34]

Poverty has settled in Kuwait more heavily since my last visit five years ago, both by sea, where the pearl trade continues to decline, and by land, where the blockade established by Saudi Arabia now harms the merchants.

Some prominent merchant families left Kuwait in the early 1930s due to the prevalence of economic hardship. At the time of the discovery of oil in 1937, most of Kuwait's inhabitants were impoverished.

Kuwait–Najd War (1919–1920)

[edit]The Kuwait–Najd War erupted in the Aftermath of World War I, when the Ottoman Empire was defeated and the British invalidated the Anglo-Ottoman Convention, declaring Kuwait to be an "independent sheikhdom under British protectorate". The power vacuum, left by the fall of the Ottomans, sharpened the conflict between Kuwait and Najd (Ikhwan). The war resulted in sporadic border clashes throughout 1919–1920. Several hundreds of Kuwaitis died.

The border of the Najd and Kuwait was finally established by the Uqair Protocol of 1922. Kuwait was not permitted any role in the Uqair agreement, the British and Al Saud decided modern-day Kuwait's borders. After the Uqair agreement, relations between Kuwait and Najd remained hostile.

Battle of Jahra

[edit]The Battle of Jahra was a battle during the Kuwait-Najd Border War. The battle took place in Al Jahra, west of Kuwait City on October 10, 1920, between Salim Al-Mubarak Al-Sabah ruler of Kuwait and Ikhwan followers of Ibn Saud of Saudi Arabia, king of Saudi Arabia.[36]

A force of 4,000 Saudi Ikhwan, led by Faisal Al-Dawish, attacked the Kuwait Red Fort at Al-Jahra, defended by 2,000 Kuwaiti men. The Kuwaitis were largely outnumbered by the Ikhwan of Najd.

The Uqair protocol

[edit]In response to the various Bedouin raids, the British High Commissioner in Baghdad, Sir Percy Cox, imposed the Uqair Protocol of 1922 which defined the boundaries between Iraq, Kuwait and Nejd. On 1 April 1923, Shaikh Ahmad al-Sabah wrote the British Political Agent in Kuwait, Major John More, "I still do not know what the border between Iraq and Kuwait is, I shall be glad if you will kindly give me this information." Major More, upon learning on 4 April that al-Sabah claimed the outer green line of the Anglo-Ottoman Convention, relayed knowledge of the claim to Sir Percy.

On 19 April, Sir Percy stated that the British government recognised the outer line of the convention as the border between Iraq and Kuwait. This decision limited Iraq's access to the Persian Gulf at 58 km of mostly marshy and swampy coastline. As this would make it difficult for Iraq to become a naval power (the territory did not include any deepwater harbours), the Iraqi King Faisal I (whom the British installed as king of Iraq) did not agree to the plan. However, as his country was under British mandate, he had little say in the matter. Iraq and Kuwait would formally ratify the border in August. The border was re-recognised in 1932.

In 1913, Kuwait was recognised as a separate province from Basra Vilayet and given autonomy under Ottoman suzerainty in the draft Anglo-Ottoman Convention, however this was not signed before the outbreak of the first World War. The border was revisited by a memorandum sent by the British high commissioner for Iraq in 1923, which became the basis for Kuwait's northern border. In Iraq's 1932 application to the League of Nations it included information about its borders, including its border with Kuwait, where it accepted the boundary established in 1923.[37]

1920s–1940s

[edit]The 1920s and 1930s saw the collapse of the pearl fishery and with it Kuwait's economy. This is attributed to the invention of the artificial cultivation of pearls.

The discovery of oil in Kuwait, in 1938, revolutionised the sheikdom's economy and made it a valuable asset to Britain. In 1941 on the same day as the German invasion of the USSR (22 June) the British took total control over Iraq and Kuwait. (The British and Soviets would invade the neighbouring Iran in September of that year).

List of Rulers

[edit]Sheikhs of Kuwait (1752–1961)

[edit]| № | Portrait | Name | Reign start | Reign end |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sabah I bin Jaber | 1752 | 1776 | |

| 2 | Abdullah I al-Sabah | 1776 | 3 May 1814 | |

| 3 | Jaber I al-Sabah | 1814 | 1859 | |

| 4 | Sabah II al-Sabah | 1859 | November 1866 | |

| 5 | Abdullah II al-Sabah | November 1866 | 29 May 1892 | |

| 6 |

|

Muhammad bin Sabah Al-Sabah | 29 May 1892 | 17 May 1896 |

| 7 |

|

Mubarak al-Sabah | 17 May 1896 | 28 November 1915 |

| 8 |

|

Jaber II al-Sabah | 28 November 1915 | 5 February 1917 |

| 9 |

|

Salim al-Mubarak al-Sabah | 5 February 1917 | 22 February 1921 |

| 10 |

|

Ahmad al-Jaber al-Sabah | 29 March 1921 | 29 January 1950 |

| 11 |

|

Abdullah al-Salim al-Sabah | 29 January 1950 | 19 June 1961 |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Anscombe 1997, p. 6

- ^ a b c d e Crystal, Jill. "Kuwait: Ruling Family". Persian Gulf States: A Country Study. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- ^ Fattah, p. 83

- ^ Ibn Agil, p. 78

- ^ Abu-Hakima, Ahmad Mustafa. "Bani Khalid, Rulers of Eastern Arabia." The Modern History of Kuwait, 1750-1965. London: Luzac, 1983. 2-3. Print

- ^ Reidar Visser (2005). Basra, the Failed Gulf State: Separatism And Nationalism in Southern Iraq. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3-8258-8799-5. Retrieved 2013-06-08.

- ^ Gazetteer of the Persian Gulf, Oman, and Central Arabia, Geographical, Volume 1, Historical Part 1, John Gordon Lorimer,1905, p1000

- ^ Abu-Hakima, Ahmad Mustafa. "Arrival of the Utub in Kuwait." The Modern History of Kuwait, 1750-1965. London: Luzac, 1983. 3-5. Print.

- ^ Shadows on the Sand: The Memoirs of Sir Gawain Bell. 1983. p. 222.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ ʻAlam-i Nisvāṉ - Volume 2, Issues 1-2. p. 18.

Kuwait became an important trading port for import and export of goods from India, Africa and Arabia.

- ^ a b c d e f g Constancy and Change in Contemporary Kuwait City. 2009. pp. 66–71. ISBN 978-1-109-22934-9.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Bennis, Phyllis; Moushabeck, Michel (31 December 1990). Beyond the Storm: A Gulf Crisis Reader. Interlink Publishing Group Incorporated. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-940793-82-8.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Hasan, Mohibbul (2007). Waqai-i manazil-i Rum: Tipu Sultan's mission to Constantinople. Aakar Books. p. 18. ISBN 9788187879565.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b Constancy and Change in Contemporary Kuwait City. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-109-22934-9.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Fattah, Hala Mundhir (1997). The Politics of Regional Trade in Iraq, Arabia, and the Gulf, 1745–1900. SUNY Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-7914-3113-9.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "The Hypothetical Population Pattern of the Population Growth of the State of Kuwait in the pre-oil era". Kuwait University. Archived from the original on 2013-10-02. Retrieved 2013-07-26.

- ^ Miriam Joyce (2006). Kuwait, 1945–1996: An Anglo-American Perspective. Routledge. p. XV. ISBN 978-1-135-22806-4.

- ^ Richard Harlakenden Sanger (1970). The Arabian Peninsula. Books for Libraries Press. p. 150. ISBN 9780836953442.

- ^ Kuwait Today: A Welfare State. 1963. p. 89.

- ^ M. Nijhoff (1974). Bijdragen tot de taal-, land- en volkenkunde, Volume 130. p. 111.

- ^ a b c d Mary Bruins Allison (1994). Doctor Mary in Arabia: Memoirs. University of Texas Press. p. 1.

- ^ Donaldson, Neil (2008). The Postal Agencies in Eastern Arabia and the Gulf. Lulu.com. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-4092-0942-3.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ ́Goston, Ga ́bor A.; Masters, Bruce Alan (2009). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. Infobase. p. 321. ISBN 978-1-4381-1025-7.

- ^ a b c d Two ethnicities, three generations: Phonological variation and change in Kuwait (PDF) (PhD). Newcastle University. pp. 13–14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-19. Retrieved 2014-05-16.

- ^ "Kuwait: A Trading City". Eleanor Archer. 2013. Archived from the original on 2014-01-01. Retrieved 2014-05-16.

- ^ a b Fattah, Hala Mundhir (1997). The Politics of Regional Trade in Iraq, Arabia, and the Gulf, 1745–1900. SUNY Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-7914-3113-9. Archived from the original on 2021-02-06. Retrieved 2016-09-25.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Potter, L. (2009). The Persian Gulf in History. Springer. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-230-61845-9.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Lord of Arabia" (PDF). H. C. Armstrong. 1905. pp. 18–19. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-05-12.

- ^ Kumar, India and the Persian Gulf Region, p.157.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Crystal, Jill (1995). Oil and Politics in the Gulf: Rulers and Merchants in Kuwait and Qatar. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-521-46635-6.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g Mary Ann Tétreault (1995). The Kuwait Petroleum Corporation and the Economics of the New World Order. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-89930-510-3. Archived from the original on 2023-01-13. Retrieved 2016-09-25.

- ^ David Lea (2001). A Political Chronology of the Middle East. p. 142. ISBN 978-1-85743-115-5.

- ^ a b Lewis R. Scudder (1998). The Arabian Mission's Story: In Search of Abraham's Other Son. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-8028-4616-7.

- ^ a b c d e f Mohammad Khalid A. Al-Jassar (2009). Constancy and Change in Contemporary Kuwait City: The Socio-cultural Dimensions of the Kuwait Courtyard and Diwaniyya. p. 80. ISBN 978-1-109-22934-9.

- ^ a b c d e Casey, Michael S.; Thackeray, Frank W.; Findling, John E. (2007). The History of Kuwait. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-57356-747-3.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ The blood red place of Jahra Archived 2012-06-05 at the Wayback Machine, Kuwait Times.

- ^ Crystal, Jill. "Kuwait – Persian Gulf War". The Persian Gulf States: A Country Study. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 5 March 2011.