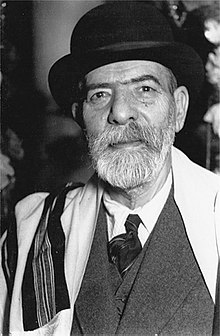

Sidi Fredj Halimi

This article relies largely or entirely on a single source. (May 2019) |

Sidi Fredj Halimi (1876 – 1957) was the Chief Rabbi of Constantine during about sixty years at the beginning of the 20th century. The meaning of his name, Fredj, in English is "consolation". Sidi Fredj is called by his relatives "Baba Laaziz", meaning "beloved father" in English.[1]

Sidi Fredj Halimi was born on October 23, 1876, in Constantine, shortly after all the Jews of Algeria received French nationality following the Crémieux Decree in 1870. He died on September 25, 1957, the eve of Jewish New Year, and was buried in the Jewish cemetery in this city. His death occurred a short time before the massive emigration of virtually all Algerian Jews, following the events of Algerian war (1961–63).

Sidi Fredj Halimi was the spiritual father of the Jews living in Constantine, and his reputation spread during his life far beyond that city, in Algeria as well in the neighboring countries of North Africa and in the Jewish community of France. He also maintained a correspondence with famous rabbis from different European countries. So far he is still one of the most revered figures of Algerian Judaism in France and in Israel. In recognition for his work for the nation, Sidi Fredj Halimi received from the French government the order of Knight of the Legion of Honour.

Biography

[edit]Fredj Halimi was the son of Rabbi Sidi Abraham Halimi (called by his relatives "Sidi Baha") and Bendkia Zerbib, called by her family "Ma Bendkia", daughter of Rabbi Shimon Zerbib. By his father's side Sidi Fredj comes from an illustrious line of rabbis, including his father Sidi Benjamin Halimi and his grandfather Rabbi Khalfalah Halimi. By his mother's side too, he comes from an illustrious line of rabbis going back to the famous Rabbi Messa'oud (also known as "El Hasid", author of Zerah Haemeth) of the 18th century.

Sidi Fredj's parents were poor, and the situation even worsened when Rabbi Abraham Halimi died when Sidi Fredj reached the age of 13. As teenager, he studied thoroughly at the Yeshiva Jewish studies: the Torah, both Talmuds, the Halakha and the Haggadah, but at the same time he had to work to support his family (his mother, his brother, Sidi Khai and his sisters, Clara and Esther). In a few years he acquired an excellent knowledge in Judaism, and this was noticed by the community leaders. He was appointed as Dayan (simple judge) at the age of 18, Rosh Beth Din (rabbinical court president) at the age of 21, and finally he was appointed as the Chief-Rabbi of Constantine at the age of 24.

Personality and influence

[edit]He was a rabbi with a boundless devotion to his community. He was in good relation with all the Jews of the community without distinction, whatever their religious or political views. He succeeded by his influence to preserve the unity of the community, that at a period of profound social and cultural upheavals due to the francization of the Algerian Jews. He also worked tirelessly to improve the plight of the poor, and was the president of many associations working in the framework of the community, such as the charity association, the Talmud Torah, etc.. An event illustrating his great fame is that the position of Chief Rabbi of Tunisia was proposed to him during the Algerian war. He refused, saying that a rabbi must be familiar with his community and this since a young age, so by attachment to his own community. We can describe his personality in this way: "His erudition and wisdom were matched by his dedication and humility".

Family

[edit]Sidi Fredj Halimi married Tefakha Bitoun (called by her relatives "Ma Tefakha") and had eight children, seven daughters (Myriam, Turkia, Pauline, Georgette, Blanche, Julie and Suzanne) as well as one son, Abner Shalom. His daughter Myriam, divorced only a few years after her wedding, died young, leaving her son Gilbert Mordechai Achour orphan at the age of 9. Then his grandparents adopted him and raised him as one of their own children. All his children left Algeria in the early sixties following Algeria's independence, settling mostly in the Paris and Marseilles regions. Some if his descendants later emigrated to Israel.

References

[edit]- ^ Simon, Reeva Spector; Laskier, Michael Menachem; Reguer, Sara (2003-04-30). The Jews of the Middle East and North Africa in Modern Times. Columbia University Press. p. 462. ISBN 978-0-231-50759-2.