Sloviansk

Sloviansk

Слов'янськ | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates: 48°51′12″N 37°37′30″E / 48.85333°N 37.62500°E | |

| Country | |

| Oblast | Donetsk Oblast |

| Raion | Kramatorsk Raion |

| Hromada | Sloviansk urban hromada |

| Founded | 1645 |

| City status | 1784 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Vadym Liakh[1] (Opposition Bloc[1]) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 58.9 km2 (22.7 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 74 m (243 ft) |

| Population (1 January 2022)[2] | |

| • Total | 105,141 |

| • Density | 1,800/km2 (4,600/sq mi) |

| In June 2022, the population was estimated less than 24,000.[3] | |

| Postal code | 84100—84129 |

| Area code | +380-6262 |

| Climate | Warm summer subtype |

| KATOTTH | UA14120210010032554 |

| Website | http://www.slavrada.gov.ua/ |

| |

Sloviansk[a] is a city in Donetsk Oblast, northern part of the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine. The city was known as Tor until 1784.[6] While it did not actually belong to the raion itself, Sloviansk served as the administrative center of the Sloviansk Raion (district) until its abolition on 18 July 2020.

Sloviansk was one of the focal points in the early stages of the war in Donbas, in 2014, as it was one of the first cities to be seized and controlled by Russian-backed rebels (separatists), in mid-April 2014.[7][8] Ukrainian forces then retook control of the city in July 2014, and since then, Sloviansk has been under Ukrainian control.

The 2001 population of Sloviansk was 141,066. Largely due to the ongoing war in Donbas, by early 2022 this was down to 105,141.[9] Following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the city's population fell markedly, to around 24,000 by July 2022, due to shelling, and ongoing war, according to Ukrainian authorities.[10] In April 2023, The Financial Times estimated the population to have recovered to 40-50,000.[11]

History

[edit]Founding and early history

[edit]The history of Sloviansk dates back to 1645 when Russian Tsar Alexei Romanov founded a border fortress named Tor[12] against the Crimean attacks and slave raids on the southern suburbs of modern Ukraine and Russia.[13] In 1664, the first salt plant for the extraction of salt was built, and workers began to settle in the area.[14] In 1676, a fortress named Tor was built at the confluence of the Kazenyy Torets and Sukhyy Torets River, where they form the Torets River, a tributary of Donets River.[15] Shortly thereafter, the town of Tor grew up next to the fortress.[13]

As several salt lakes were located close by, the town soon became a major producer of salt. During the sixteenth century, salt production was the principal local industry. In 1784, the city was renamed Slovenske, and a decade later, Sloviansk (Slavyansk). [16]

In 1827, military doctor A. Yakovlev was the first to use mud treatment and bathing in Lake Ropne to treat sick soldiers. Four years later, a military hospital of 200 beds was opened near the lake, where mud therapy was used. In 1832, the first resort was established on the shores of Lake Ropne.[17] With the construction of a railway line in 1869, the town grew rapidly, from a population of 5,900 in 1847 to 15,700 by 1897.[16]

20th century

[edit]

In April 1918, troops loyal to the Ukrainian People's Republic briefly took control of Sloviansk.[18] Sloviansk was then, along with the rest of Ukraine, incorporated into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

In World War II, the city was occupied by Nazi Germans on 28 October 1941. In December 1941, the SS Einsatzkommando 4b murdered more than a thousand Jews who lived in Sloviansk.[19] The Red Army temporarily expelled the Nazi occupiers on 17 February 1943. Germans retook it on 1 March 1943. The Red Army finally liberated Sloviansk on 6 September 1943.

Salt extraction in Sloviansk in turn gave rise to salt refining and packaging, soda and other chemical manufacturing. By 1972 there were 18 related enterprises in the city, including plastics and the making of vinyl records.[16] Sloviansk reached its peak population of 143,000 in 1987. Sloviansk would remain as part of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic until its dissolution in 1991, after which the city became part of an independent Ukraine.[16]

Siege of Sloviansk

[edit]The 2014 Ukrainian revolution for the most part passed Sloviansk by, with no large-scale gatherings or events in the city, and polls showing people in the east of Ukraine to be largely opposed to the Maidan movement in Kyiv.[20] However, Sloviansk would quickly become the epicentre of events following the fallout of the revolution. On 12 April 2014, in the crisis and chaos which gripped the country following the revolution's installing of the First Yatsenyuk government, a reported 55 armed men, led by Russian military veteran Igor Girkin, known as 'Igor Strelkov' stormed Sloviansk, quickly capturing the executive committee building, the police department, and the SBU office of the city.[21][22][23] Ukrainian Interior Minister Arsen Avakov described the gunmen as "terrorists" and vowed to use the Ukrainian special forces to retake the buildings.[24][25] On 13 April 2014, there were reports of fighting between the gunmen and Ukrainian troops, with casualties reported on both sides.[26][27] The BBC's David Stern described the pro-Russian forces as carrying Russian weapons and resembling the soldiers that took over Crimean installations at the start of the 2014 Crimean crisis.[26][28]

Initially, the pro-Russia rebels enjoyed strong support, with the New York Times reporting: "Thousands of residents thronged a large square in front of City Hall to welcome the pro-Russian putsch, chanting “Russia, Russia” and posing for photographs with gunmen they hailed as their saviors from the fascists who had seized power in Kiev with the February ouster of President Victor F. Yanukovych, a Russian-speaker from Donetsk."[29]

Elected mayor of Sloviansk Nelya Shtepa gave a series of contradictory statements on her support for the pro-Russia side, and was then taken captive by the pro-Russia side. Shtepa would be one of several high-profile detainments during rebel control of Sloviansk. [30] On 14 April the pro-Russia side installed their own 'people's mayor' Vyacheslav Ponomarev, to deal with civilian matters, and press, while Strelkov / Girkin took charge of military matters.[31] Throughout April, and May, Ponomarev would hold near daily press conferences in the city's admininstrative building.[32] On 9 May, Victory Day, there was a parade, and large gathering of people in the central Square of Sloviansk. Nelya Shtepa appeared, the first time she had been seen in public since mid-April, and gave a pro-Russian speech on stage, urging people to vote in the referendum scheduled for 11 May. Recently freed rebel leader Pavel Gubarev also appeared on stage.[33] Referendums went ahead across Donbas on 11 May, including Sloviansk, with the pro-Russia side reporting a turnout of near 75%, with over 90% voting for self rule as part of the Donetsk/Luhansk People's Republics. However, the referendums were not monitored, or endorsed, by any international observers, or organisations, and their results almost universally unrecognised in the west. Russia issued a statement saying they 'respected' the results of the referendums, but stopped short of recognising them.[34][35]

Fighting intensified throughout May, as Ukrainian forces escalated their 'ATO' (Anti-Terror Operation) to retake the city, with a Ukrainian military helicopter shot down at the start of the month, and multiple casualties reported in fighting on both sides.[36] May would also see escalating civilian casualties in Sloviansk, as Ukrainian forces began their assault on the city. On 5 May, 30-year-old Irina Boevets was killed by a stray Ukrainian bullet, as she stepped out on her balcony. The Guardian at the time reported these civilian deaths as "fuelling pro-Russian sentiment".[37] Fighting between sides would wage in May, with increasing intensity. A follow-up referendum to the referendum on 11 May had been planned for 18 May, giving voters the option of joining Russia, however this was abandoned due to the escalation of fighting. On 29 May 2014, a Ukrainian helicopter carrying fourteen Ukrainian special service soldiers, including General Serhiy Kulchytskiy – the head of combat and special training for Ukraine's National Guard, crashed after being shot down by militants near Sloviansk. Ukraine's outgoing President Olexander Turchynov described the downing as a "terrorist attack," and blamed pro-Russian militants.[38]

As June went on, it became clear that the pro-Russia side were losing the battle for Sloviansk, beset by a number of problems, including infighting, with enmity between 'people's mayor' Ponomarev, and Strelkov/Girkin, resulting in Strelkov/Girkin having Ponomarev arrested, and dismissed from his duties, on 12 June.[31] Ukrainian forces further stepped up their shelling of Sloviansk in June.[39] Sloviansk was ultimately held by Russian-backed rebels for nearly three months, from mid-April until 5 July 2014, during which time fighting between the rebels and the Ukrainian army escalated, along with shelling of civilian areas of the city, with both military and civilian casualties.[40] In late June, the Ukrainian army started advancing on Sloviansk, taking strategically significant locationed, including the Karachun Mountains. This, combined with Strelkov's videos decrying a lack of support, made the rebel retreat an inevitability.[41][42] A 10-day ceasefire, not entirely observed by either side, ended on 30 June, and in early July, faced with a full-on Ukrainian offensive, Strelkov co-ordinated the retreat of his forces from Sloviansk.[43] Initially they had planned to go to nearby Kramatorsk, however when it became clear that the Ukrainian army would also take Kramatorsk, which they duly did, most headed to Donetsk, which would then become their stronghold.[44]

Sloviansk was one of several territories taken by Ukrainian forces at this time, including the nearby cities of Kramatorsk, and Kostiantynivka.[45] Although Sloviansk's capture was a military victory for Ukrainian forces, the successful co-ordinated retreat of the rebel forces, and fall back to a fortified Donetsk, led to accusations, and recriminations, from the Ukrainian side.[46]

General Serhiy Krivonos, Deputy Secretary of the National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine, said in 2020 that the Ukrainian Army was aware of the movement of Girkin's columns out of Sloviansk but did not attack the columms:

Having some information from our sources from Sloviansk and Kramatorsk, we understood that they [the separatists] would come out. This understanding was clearly formed between 2 and 3 July. And already on the 4th it was clear that they would leave that night from 4 to 5 July. We actively conducted reconnaissance and gave coordinates directly on the night movement of the column, and on the daytime location of the enemy in Kramatorsk, and then on the exit of Girkin's columns from Kramatorsk. These coordinates were given. There was no implementation of [an attack on] these coordinates.[47]

A series of incidents, and a difficult ongoing living situation had resulted in support for the pro-Russian rebels eroding in the near three months that Sloviansk was under their control. The New York Times reported that 'many of the same people' who had once supported the pro-Russia rebels 'rushed into the same square to greet Ukrainian military trucks as soldiers handed out free food. Virtually nobody now admits to having supported the separatists.' Konstantin Batozsky, an aide to the Kyiv-appointed governor of the Donetsk region, which included Sloviansk, stated of the people of Sloviansk: “They are happy to welcome whoever gives them food.” [29]

Aftermath of the siege and decommunization

[edit]Following Ukraine's recapture of Sloviansk in July 2014, Ukrainian authorities began a 'hunt' for collaborators, setting up a hotline encouraging residents of the city to inform on those who had 'collaborated with pro-Russian rebels'. There were further discoveries of 'mass graves'. The New York Times reported at this time "There is no mood of joyous celebration at what Ukrainian officials trumpet as the city’s “liberation.” Anger and animosity bubbles just below the calm surface. In each workplace, everyone knows who did what during rebel rule, creating poisonous currents of suspicion."[29] The population of Sloviansk had fallen to around 80,000 at this time.

In 2015, as part of Ukraine's process of decommunization, the fate of Sloviansk's statue of Lenin, in the city's central square, became a topic of heated debate at council meetings. Large factions from Ukrainian ultra-national groups Svoboda and the Right Sector attended these meetings, in support of the removal / destruction of the statue. There were also locals in favour of keeping the statue, with a petition of 4,500 signatures supporting the Lenin statue remaining. No consensus had been reached, when in the early hours of June 3, Right Sector militants tore the statue down.[48] Also in 2015, a plaque to the memory of Volodymyr Rybak, a Ukrainian politician killed by pro-Russian rebels in 2014, was placed in the town center.[49]

Although war continued in parts of Donbas, there were no notable incidents in Sloviansk following its recapture by Ukrainian forces in July 2014, until 2022. In 2016, the city was visited by Orlando Bloom in his role as a UNICEF goodwill ambassador.[50] The population of Sloviansk would recover in the years up to 2022, to pre-2014 level.[16]

Russian invasion of Ukraine

[edit]

Sloviansk has been affected from the start of the 2022 Invasion of Ukraine, without becoming a central theatre of war.[11] Sloviansk has been described as being a "crucial part Moscow’s objective of capturing all of the Donbas region".[51]

The city has several times fallen under shelling, with the loss of civilian life.[52][53][54] An April 2023 profile of Sloviansk by the Financial Times described the city as being like a 'ghost town', with mayor Vadym Lyakh having given an order to evacuate. The population of Sloviansk at this time was estimated at 40-50,000, up from 2022's estimate of 24,000, but significantly down from the pre-Russian invasion population of over 100,000.[11] In September 2023, The Guardian reported from a Sloviansk still on a war footing.[55]

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1897 | 15,792 | — |

| 1926 | 28,385 | +79.7% |

| 1939 | 77,842 | +174.2% |

| 1959 | 82,784 | +6.3% |

| 1970 | 124,183 | +50.0% |

| 1979 | 140,256 | +12.9% |

| 1989 | 135,300 | −3.5% |

| 2001 | 124,829 | −7.7% |

| 2011 | 118,602 | −5.0% |

| 2022 | 105,141 | −11.3% |

| Source: [56] | ||

According to the 2001 Ukrainian Census:[57]

| Ethnicity | ||

|---|---|---|

| Ukrainians | 104,423 | 73.1% |

| Russians | 33,649 | 23.6% |

| Turks | 829 | 0.6% |

| Belarusians | 766 | 0.5% |

| Armenians | 592 | 0.4% |

| Greeks | 320 | 0.2% |

| Roma people | 279 | 0.2% |

| Azerbaijanis | 208 | 0.1% |

Total 2001 population: 141,066

Geography

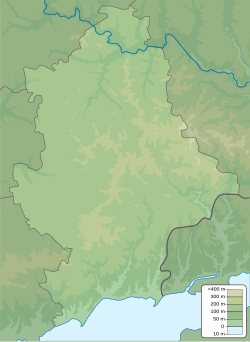

[edit]Sloviansk is in the valley of the Kazennyi Torets River, a right tributary of the Donets, in the Donbas region.

Karachun Mountains are the highest point of Sloviansk, situated to the south of the city.[58]

Climate

[edit]The climate in Sloviansk is a mild to warm summer subtype (Köppen: Dfb) of the humid continental climate.

| Climate data for Sloviansk | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −5.9 (21.4) |

−5.4 (22.3) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

9.4 (48.9) |

16.2 (61.2) |

20.0 (68.0) |

21.7 (71.1) |

20.8 (69.4) |

15.5 (59.9) |

8.4 (47.1) |

1.8 (35.2) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

8.3 (46.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 45 (1.8) |

34 (1.3) |

27 (1.1) |

39 (1.5) |

42 (1.7) |

57 (2.2) |

51 (2.0) |

40 (1.6) |

39 (1.5) |

30 (1.2) |

42 (1.7) |

44 (1.7) |

490 (19.3) |

| Source: Climate-Data.org[59] | |||||||||||||

Economy and Industry

[edit]

- Before the war in 2014, Sloviansk was an important industrial and health resort center, providing spa treatments and mud baths using mud from the bottom of salt lakes located nearby, and attracting tourists from across Ukraine and beyond. After sustaining damage in 2014, some of the city's resort facilities were repaired, and operated until active war broke out in Sloviansk again in 2022. As of 2023, none of Sloviansk's spa resorts or tourist facilities are in operation.[60]

- The Slovvazhmash heavy-machinery production plant, specialised in chemical equipment for coke production.[16]

- The Betonmash machine-building factory, specialised in concrete mixing plants, spare parts for mining equipment and metal works, parts for coke ovens.[61]

- The Sloviansk mechanical plant, specialised in coke production as well as overhead cranes and other machinery.[62]

Transport

[edit]

Sloviansk is a nexus of a number of railways and roads. The city is served by three railway passenger stations: Slovianskyi Resort (in the northeast), ‘Mashchormet’ (at the junction), and 'Sloviansk' (the main station, west of the junction, on the southwest side of the city). Three railway lines leave the city in directions of Lozova, Lyman and Kramatorsk. The local population is served by a trolleybus network consisting of two permanent routes and one summer route. Marshrutkas are widely used.

The M03 goes by the edge of Sloviansk. In early 2015, Ukraine lost control of the section of this from Debaltsevo on, then in early 2023 Ukraine lost control of the section from Soledar to Debaltsevo. H20 leaves from the city toward Mariupol, via Kramatorsk, Kostiantynivka, Donetsk, and Volnovakha. Ukraine lost control of part of this highway, around Donetsk, in 2014. The first part of 2022 saw fierce fighting on or around the highway, and by summer of 2022, Ukraine had lost control of the H20 highway, from around Donetsk onto Mariupol.

Religious organizations

[edit]

Christian churches:

- Cathedral of New Martyrs and Confessors of the Russian Orthodox Church

- Church of the Resurrection of Christ

- Church of the Andrew the Apostle

- Church of Oleksandr Nevskyi

- Church of Seraphim Sarovsky

- The "Kind New" Christian Center Church

- Church of Jesus Christ of the Protestant Church of Ukraine

Notable people

[edit]- Yuri Bogatikov (1932-2002), Soviet-Ukrainian singer

- Viktor Fomin (1929-2007), Soviet-Ukrainian football player

- Vsevolod Kovalchuk (born 1978), Ukrainian businessman

- Ivan Maistrenko (1899-1984), Ukrainian revolutionary

- Maksym Marchenko (born 1983), Ukrainian colonel, former governor of Odesa Oblast (March 2022 to March 2023)

- Oleksandr Mashchenko (born 1985), Ukrainian paralympic swimmer

- Dmytro Miliutenko (1899-1966), Soviet-Ukrainian actor

- Mykhailo Petrenko (1817-1863), Ukrainian poet

- Nikolai Semeyko (1923-1945), Soviet aviator

- Viktor Smyrnov (born 1986), Ukrainian paralympic swimmer

- Mykhaylo Sokolovsky (born 1951), a Soviet-Ukrainian footballer, record holder of the games played for Shakhtar Donetsk

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Ukrainian: Слов'янськ, IPA: [slou̯ˈjɑnʲsʲk] ; Russian: Славянск, romanized: Slavyansk,[4] IPA: [slɐˈvʲansk] or [ˈslavʲɪnsk][5]

References

[edit]- ^ a b CEC names winners of mayoral elections in Uzhgorod, Berdiansk, Sloviansk, Interfax-Ukraine (23 November 2020)

- ^ Чисельність наявного населення України на 1 січня 2022 [Number of Present Population of Ukraine, as of January 1, 2022] (PDF) (in Ukrainian and English). Kyiv: State Statistics Service of Ukraine.

- ^ "80% of the population of Slovyansk have evacuated". 7 June 2022.

- ^ "Slavyansk: Ukraine". Geographical Names. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ^ Словарь географических названий СССР [Dictionary of geographical names of the USSR] (in Russian).

- ^ "СЛОВ'ЯНСЬК, МІСТО ДОНЕЦЬКОЇ ОБЛ". resource.history.org.ua. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^ "'Casualties' in Ukraine gun battles". BBC News. 13 April 2014. Retrieved 9 December 2018.

- ^ "Семнадцать километров мы шли маршем через границу". Svpressa. 11 November 2014. Archived from the original on 13 April 2022. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ^ "Sloviansk population in 2022".

- ^ "80% of the population of Slovyansk have evacuated".

- ^ a b c "'Like a ghost town': Slovyansk locals live in fear of Russia's return". Financial Times. 26 April 2023. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ Горбунов-Посадов, М.М. (2020). "БОЛЬШАЯ СОЮЗНАЯ ЭНЦИКЛОПЕДИЯ". Проектирование цифрового будущего. Научные подходы. АО "РИЦ "ТЕХНОСФЕРА": 82–87. doi:10.22184/978.5.94836.575.6.82.87. ISBN 9785948365756. S2CID 226479750.

- ^ a b "Города и области Украины. Справочник по Украине". Ukrainian.SU. Archived from the original on 16 August 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2010.

- ^ "Славянск - город Тор, курорт и воин". sotok.net. Archived from the original on 23 January 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ "Slov'yansk (Ukraine) - Encyclopædia Britannica". Britannica.com. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f "Encyclopedia of Ukraine". Retrieved 6 December 2023.

- ^ Славянск // Курорты: энциклопедический словарь / редколл., гл. ред. Е. И. Чазов. М., «Советская энциклопедия», 1983. стр.313

- ^ (in Ukrainian) 100 years ago Bakhmut and the rest of Donbass liberated, Ukrayinska Pravda (18 April 2018)

- ^ "Yahad - in Unum".

- ^ "70% жителей Донбасса по-прежнему считают Евромайдан государственным переворотом" [70 % of the residents of Donbass still think Euromaidan was an overthrow of government] (in Russian). 20 November 2014. Retrieved 6 December 2023.

- ^ "Igor Girkin was one of three convicted of murder over the MH17 attack and is the elusive figure behind Vladimir Putin's war in Ukraine". ABC Australia. 19 November 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- ^ Rachkevych, Mark (12 April 2014). "Armed pro-Russian extremists launch coordinated attacks in Donetsk Oblast, seize buildings and set up checkpoints". Kyiv Post.

- ^ "Where to go on Independence Weekend: places where free Ukraine was being born".

- ^ "Armed men seize police department in east Ukraine: minister". Reuters. 12 April 2014. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- ^ "Gunmen seize Ukraine police station in Sloviansk". BBC News. 12 April 2014. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Ukraine crisis: Casualties in Sloviansk gun battles". BBC News. 13 April 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine Army Launches 'Anti-Terror' Operation". Sky News via Yahoo! News. 13 April 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine crisis: Rebels abandon Sloviansk stronghold". BBC News. 5 July 2014. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ a b c "A Test for Ukraine in a City Retaken From Rebels". NY Times. 1 August 2014. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ^ "In Ukraine's east, mayor held hostage by insurgent". Yahoo News. Associated Press. 22 April 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- ^ a b "Pro-Russian mayor of Slavyansk sacked and arrested". Guardian. 12 June 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ^ "Vyacheslav Ponomarev: the 'people's mayor' who runs Slavyansk". Guardian. 25 April 2014. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ^ "На Параде в Славянске выступила Штепа и Губарев" [At the Parade in Slavyansk, Shtepa and Gubarev gave speeches] (in Russian). 9 May 2023. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- ^ "Ukraine rebels hold referendums in Donetsk and Luhansk". BBC News. 11 May 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- ^ "Russia respect decision to split from Ukraine". 12 May 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- ^ "Ukraine soldiers killed in renewed Sloviansk fighting". BBC News. 5 May 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2023.

- ^ "Ukraine soldiers killed in renewed Sloviansk fighting". Guardian. 7 May 2014. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ "General, 13 soldiers killed as militants down military helicopter". Russia Herald. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ "Shelling in Slaviansk". Reuters. 18 June 2014. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- ^ "Obama: Ukraine 'Vulnerable' To Russian 'Military Domination'". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. 11 March 2016. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- ^ Tsvetkova, Maria (5 July 2014). "Ukraine government forces recapture separatist stronghold". Reuters. Archived from the original on 4 February 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ AFP (20 April 2011). "Pro-Russia rebels and commander flee Slavyansk". Yahoo News. Archived from the original on 15 July 2014. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ "Pushed from Slaviansk, Ukraine rebels barricade Donetsk". Reuters. 8 July 2014. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ "Ukraine President Poroshenko hails 'turning point'". BBC. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine marks 7th anniversary of Kramatorsk, Sloviansk liberation". Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ Свобода, Радіо (6 July 2020). "Був шанс завершити АТО раз і назавжди – Забродський про втечу бойовиків Гіркіна зі Слов'янська". Радіо Свобода (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ Свобода, Радіо (6 July 2020). "Ми давали координати колон, реалізації не було – Кривонос про вихід бойовиків Гіркіна зі Слов'янська". Радіо Свобода (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ "Goodbye, Lenin: how a weighty symbol of the Soviet past divided a Ukrainian city". 21 June 2015. Retrieved 2 June 2023.

- ^ "Remembering Volodymyr Rybak: a year since the murder". EMPR: Russia - Ukraine war news, latest Ukraine updates. 18 April 2015. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ "Orlando Bloom makes surprise visit to Ukraine". 29 April 2016. Retrieved 21 November 2023.

- ^ Rob Picheta (6 April 2022). "The fight for Sloviansk may be 'the next pivotal battle' of Russia's war in Ukraine". CNN. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ "At least 2 killed in Russian shelling of Sloviansk". 5 July 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ "v". 27 March 2023. Retrieved 17 December 2023.

- ^ Pfaffenbach, Kai (15 April 2023). "Eleven killed in Russian strike, Ukraine rescue teams sift through wreckage". Reuters. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

- ^ "'It felt like the beginning of the third world war … It still does' – Mstyslav Chernov on 20 Days in Mariupol". 29 September 2023. Retrieved 17 March 2024.

- ^ "Cities & Towns of Ukraine".

- ^ Національний склад та рідна мова населення Донецької області [Ethnic and linguistic composition of Donetsk Oblast] (in Ukrainian). Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- ^ "KARACHUN MOUNTAIN, SLOVYANSK". Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ "Climate: Sloviansk". Climate-Data.org. Retrieved 2 May 2014.

- ^ "Discover Ukraine". Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ "Betonmash". Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ "Kompass". Retrieved 8 December 2023.

External links

[edit]- (in Russian, Ukrainian, and English) Official website

- (in Russian) Unofficial website of Slavjansk Trolleybus system

- Marble sculpture of Nicolai Shmatko

- Sloviansk

- Cities in Donetsk Oblast

- Izyumsky Uezd

- Populated places established in 1645

- Populated places established in 1676

- Cities of regional significance in Ukraine

- 1676 establishments in Ukraine

- Holocaust locations in Ukraine

- Cities and towns built in the Sloboda Ukraine

- Populated places established in the 17th century

- Sloviansk urban hromada