Stone Mountain Memorial half dollar

United States | |

| Value | 50 cents (0.50 US dollars) |

|---|---|

| Mass | 12.5 g |

| Diameter | 30.61 mm (1.20 in) |

| Thickness | 2.15 mm (0.08 in) |

| Edge | Reeded |

| Composition |

|

| Silver | 0.36169 troy oz |

| Years of minting | 1925 |

| Mint marks | None, all coins struck at the Philadelphia Mint without mint mark |

| Obverse | |

| |

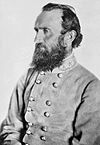

| Design | Portrait of Confederate Generals Robert E. Lee (right) and Stonewall Jackson (left) |

| Designer | Gutzon Borglum |

| Design date | 1925 |

| Reverse | |

| |

| Design | Eagle perched on a mountain crag; inscription to the bravery of the soldiers of the South |

| Designer | Gutzon Borglum |

| Design date | 1925 |

The Stone Mountain Memorial half dollar was an American fifty-cent piece struck in 1925 at the Philadelphia Mint. Its main purpose was to raise money on behalf of the Stone Mountain Confederate Monumental Association for the Stone Mountain Memorial near Atlanta, Georgia. Designed by sculptor Gutzon Borglum, the coin features a depiction of Confederate generals Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson on the obverse and the caption: "Memorial to the Valor of the Soldier of the South" on the reverse. The piece was also originally intended to be in memory of the recently deceased president, Warren G. Harding, but no mention of him appears on the coin.

In the early 20th century, proposals were made to carve a large sculpture in memory of General Lee on Stone Mountain, a huge rock outcropping. The owners of Stone Mountain agreed to transfer title on condition the work was completed within 12 years. Borglum, who was, like others involved, a Ku Klux Klan member, was engaged to design the memorial, and proposed expanding it to include a colossal monument depicting Confederate warriors, with Lee, Jackson, and Confederate President Jefferson Davis leading them.

The work proved expensive, and the Association advocated the issuance of a commemorative half dollar as a fundraiser for the memorial. Congress approved it, though to appease Northerners, the coin was also made in honor of Harding, under whose administration work had commenced. Borglum designed the coin, which was repeatedly rejected by the Commission of Fine Arts. All reference to Harding was removed from the design by order of President Calvin Coolidge.

The Association sponsored extensive sales efforts for the coin throughout the South, though these were hurt by the firing of Borglum in 1925, which alienated many of his supporters, including the United Daughters of the Confederacy. A 1928 audit of the fundraising showed excessive expenses and misuse of money, and construction halted the same year; a scaled-down sculpture was eventually completed in 1970. Because of the large quantities issued—over a million remain extant—the Stone Mountain Memorial half dollar remains inexpensive compared with other U.S. commemoratives.

Background

[edit]The first European-descended settlers inhabited the land around Stone Mountain, Georgia, today in the east Atlanta suburbs, around 1790. They called the large outcropping, about 2 miles (3.2 km) long and 1,686 feet (514 m) high, "Rock Mountain". Rev. Adrel Sherwood of Macon, Georgia, first named it Stone Mountain in 1825. The town of New Gibraltar was founded nearby in 1839; its name would be changed to Stone Mountain by the Georgia Legislature in 1947. From about the time of the American Civil War, the mountain was used as a quarry; this would not entirely cease until the 1970s.[1]

John Gutzon de la mothe Borglum (usually called Gutzon Borglum) was born in Idaho Territory in 1867, to one of several wives of a Dane who had converted to Mormonism. As a boy, Borglum lived in various places in the Far West. Turning to art as a career, he attended the San Francisco Art Academy, the Académie Julian, and the École des Beaux-Arts. Greatly influenced by Rodin, whom he met, Borglum switched from painting to sculpture in 1901. His Mares of Diomedes won a gold medal at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, and became the first work of sculpture to be purchased by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[2]

Inception

[edit]

In 1914, editor John Temple Graves wrote in the Atlanta Georgian, suggesting the establishment of a memorial to Confederate General Robert E. Lee on Stone Mountain, "from this godlike eminence let our Confederate hero calmly look history and the future in the face!"[3] Others who called for the establishment of a Confederate memorial there included William H. Terrell, an Atlanta attorney who believed that while the North had spent millions of dollars on monuments to the Union, the South had not sufficiently honored Confederate heroes. Also active in the early days of the Stone Mountain proposal was Helen Plane (1829–1925), who had been a belle from Atlanta before the war, and whose husband had given his life at the Battle of Antietam in 1862. She devoted the remainder of her life to preserving the memory of the Southern cause.[4]

The release of the film The Birth of a Nation in 1915 sparked increased interest in the Confederate cause in the South.[5] Plane, who was lifetime honorary president of the Georgia organization of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), asked Borglum to carve the image of General Lee on the mountain. The Stone Mountain project was initially a UDC endeavor.[4][6] Officials originally contemplated a monument of perhaps 20 feet (6.1 m) by 20 feet (6.1 m). Putting that on Stone Mountain, Borglum supposedly stated, would be like putting a postage stamp on a barn. He proposed a much larger sculpture, 200 feet (61 m) high and 1,300 feet (400 m) long, and drew up plans in his Stamford, Connecticut, studio.[7] He envisioned a huge depiction of the Confederate army, including artillery and infantry, as well as 65 Confederate generals, five to be nominated by the governor of each Southern state.[6] In 1917, the Stone Mountain Confederate Monumental Association (the Association) was founded to publicize and raise funds for a colossal sculpture at Stone Mountain.[8] Samuel H. Venable and his family, owners of the land, agreed to deed it over for a monument, on condition that if the project was not completed in 12 years, title would revert to them. A formal dedication took place in May 1916;[7] the preliminary work was interrupted by the US entry into World War I in 1917.[9]

Another organization which took an interest in the Stone Mountain work was the recently revived Ku Klux Klan, of which both Venable and Borglum were members. The Klan, through much of the 20th century, held regular encampments on or near Stone Mountain.[6] Plane, in a 1915 letter to Borglum, stated that the original Klan had saved the South from "Negro domination" in the Reconstruction era, and suggested that the design include a small group of Klansmen in robes, seen in the distance, approaching.[10]

Beginning in 1920, the project slowly came under the control of Atlanta businessmen, brought in to aid with the massive fundraising, and the UDC became marginalized.[11] The work on the sculpture resumed on June 18, 1923, when Borglum began carving Lee's figure into the mountainside; he planned for General Stonewall Jackson and Confederate President Jefferson Davis to be close by Lee. Borglum's plans were for a huge sculpture depicting the Confederates, a memorial hall hewn from the granite at the base of the mountain in which artworks and artifacts could be displayed (as well as rolls of honor listing the contributors) and a giant amphitheater nearby. He estimated the total cost at $3.5 million. Instead, the scope of the project was scaled back, though different sources give varying cost estimates and dimensions. Borglum signed a contract to complete the group of Lee, Jackson, and Davis within three years for a cost of $250,000.[7]

The work was expensive and by November 1923, the Association decided to advocate for a commemorative coin which it could buy from the government at face value and sell at a premium as a fundraiser.[7] Two men each sought credit for coming up with the idea for a coin. Daniel W. Webb, executive secretary of the Association, said he had thought of it after finding an Alabama Centennial half dollar at home; journalist Harry Stillwell Edwards made a similar claim and apparently collected a reward from the Association.[7]

On November 16, 1923, Edwards wrote to Bascom Slemp, secretary to President Calvin Coolidge (the previous president, Warren G. Harding, had recently died). Edwards arranged a meeting between the President and himself, association president Hollins N. Randolph (an Atlanta lawyer and direct descendant of early president Thomas Jefferson), and Borglum.[12][13] President Coolidge agreed to support authorizing legislation for a Stone Mountain coin.[7]

Borglum later stated that the Association asked him to write to people in Washington because of his contacts in the Republican Coolidge administration.[14] He wrote to the powerful Republican Massachusetts senator, Henry Cabot Lodge, urging him to support legislation for a Stone Mountain commemorative coin; the appeal apparently worked, as late in 1923 the committee chairmen having jurisdiction over coinage, Reed Smoot in the Senate and Louis Thomas McFadden in the House of Representatives, introduced legislation for a Stone Mountain Memorial half dollar. McFadden later wrote that he sponsored the legislation because of his friendship with Borglum. With the threat of sectional opposition if the coin only honored the South, the bill's sponsors included language making the new half dollar also in memory of the recently deceased Harding (an Ohioan), during whose presidency the renewed work had begun. The bill passed by unanimous consent in the House on March 6, 1924, and in the Senate five days later; Coolidge signed it on March 17.[15][16] The bill authorizing the coin read:

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That in commemoration of the commencement on June 18, 1923, of the work of carving on Stone Mountain, in the State of Georgia, a monument to the valor of the soldiers of the South, which was the inspiration of their sons and daughters and grandsons and granddaughters in the Spanish-American and World Wars, and in memory of Warren G. Harding, President of the United States of America, in whose administration the work was begun ...[17]

Preparation and design

[edit]

Borglum was busy between the passage of the bill and the end of May 1924, first working on the Children's Founders Roll medal, and then the half dollar. The Children's Founders Roll was open to white children up to the age of 18 who contributed one dollar to the building of the monument. Borglum must still have been fine-tuning the monument's design; Jackson's posture on the medal differs from that on the coin.[18] Unlike the issued coin, Borglum's models showed the front part of Davis's horse, although the Confederate president is unseen, and marching soldiers appear in the background.[19] Borglum met with Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon who questioned first why "In God We Trust" appeared directly over Lee's head; Borglum responded that it was to pay tribute to the Confederates' faith. Mellon then asked what the thirteen stars on the obverse represented; Borglum replied that those on the north side of the Mason–Dixon line could consider them to represent the thirteen original colonies (those south of it, the implication was, could consider them to be a tribute to the Southern states). Mellon laughed and gave preliminary approval.[20] On July 2, Mellon showed the designs to President Coolidge; they were then sent to the Commission of Fine Arts for its members' opinions.[18]

According to numismatists William D. Hyder and R.W. Colbert, "Borglum, to put it mildly, was a temperamental artist who managed to offend most everyone with whom he worked".[8] They note that "Borglum's past insolence had not left him in the good graces of the art community" and his designs met a hostile reception at the commission.[18] Sculptor member James Earle Fraser, designer of the Buffalo nickel, rejected Borglum's initial design on July 22, eight days after they were received. The inscription on the reverse included a tribute to Harding; Fraser deemed it inartistic. Borglum submitted a second set on August 14, this was again rejected; the commission criticized the design, which seemed to be only a segment of a larger one, rather than specifically designed to fit a half dollar. Borglum wanted to ignore what he deemed "damn fool suggestions", but the Association threatened to fire him if he did not complete the coin. Borglum was concerned the reverse was still too crowded, and proposed leaving off the eagle,[21] but space was saved when Coolidge did not like the reference to Harding, and it was omitted.[22] With the eagle still in place on the reverse, Fraser finally approved the designs on October 10, 1924.[23] In all, Borglum made nine plaster models for the design.[20]

Even though all necessary approvals had been received, the Philadelphia Mint refused to proceed with preparations because of the lack of the mention of Harding, which it believed was congressionally mandated. Borglum wired Coolidge on October 31, notifying him of the problem; the President confirmed his approval of the design the following day.[24] Despite the support of the federal government for the coin, the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), an organization of Union Civil War veterans, tried to prevent the issuance of a coin they believed honored treason by lobbying in late 1924 and early 1925.[25] Work on the sculpture slowed (the head of Jackson was then being carved) because of the sculptor being distracted by designing the coin, flaws in the rock on Stone Mountain, and the fact that the Association had ceased fundraising efforts in anticipation of a campaign to sell the coin. Revenues from the medal were not sufficient to meet expenses.[25]

The obverse of the half dollar depicts Confederate generals Lee and Jackson, the latter with head bare, mounted on horseback. Although both Lee and Jackson were respected in the North, Davis would not have been acceptable on a federal coin, and he was omitted, although he appears on the Children's Founders Roll medal which Borglum adapted for the obverse of the half dollar.[26] There are thirteen stars in the upper field of the obverse; they represent the thirteen states which either joined the Confederacy or had Confederate factions. Borglum's initials, "GB", are found on the extreme right of the piece, near the horses' tails. The reverse depicts an eagle with wings stretched, representative of liberty, perched upon a mountaintop. There are 35 stars in the field, supposedly to represent the number of states at the start of the Civil War, although there were in fact 34 in 1861, and there were 35 states only from 1863 to 1864, between the admissions of West Virginia and Nevada.[5][27]

Art historian Cornelius Vermeule, writing in 1971, noted that the half dollar represents an unusual circumstance in American art, where a designer uses a coin as a bozzetto or small-scale model of a work to be completed. Vermeule considered the children's medal a better work of art, due to the inclusion of Davis. He believed that Borglum's original design, before its rejection by the Commission of Fine Arts, was superior, as it included a sense of motion through the depiction of marching soldiers in the background, balanced by the inclusion of the head of Davis's horse, though the Confederate president himself is unseen. According to Vermeule, the original design "would have made a magnificent coin, an unusual compression of monumentality and power into a limited and unorthodox historical space".[28]

Production and conflict

[edit]

The Medallic Art Company of New York converted Borglum's models to coinage dies.[22] The first 1,000 Stone Mountain Memorial half dollars were struck on a medal press at the Philadelphia Mint on January 21, 1925, the 101st anniversary of General Jackson's birth; Borglum and officials of the Association were present. The first piece struck was mounted on a plate made of gold mined in Georgia for presentation to President Coolidge.[29] The second was mounted on a silver plaque, and presented to Secretary Mellon.[30] The remainder of the first thousand were placed in numbered envelopes; some were presented to officials or those involved in the Stone Mountain project.[31] Between January and March 1925, that mint struck 2,310,000 of the authorized mintage of 5,000,000, plus 4,709 pieces reserved for inspection by the 1926 Assay Commission.[22] Except for the first thousand, for which Randolph paid in gold, the pieces were sent to the Federal Reserve Bank in Atlanta, which advanced the funds to purchase them from the government.[32]

Although the Association unveiled the completed head of Lee on January 19, 1924 (the general's birthday), within months, its relations with Borglum had become strained. Technical problems over the medal and the work on the mountain caused tensions, and political differences between Borglum, a Republican, and Randolph, an active Democrat, led to poor relations between the two. Borglum, Venable, and Randolph backed different KKK members for national leadership.[33] Both Borglum and the Association accused each other of graft; the sculptor proposed that he form a syndicate to purchase the half dollars from the Mint and sell them with the profits to be applied directly to construction costs. Randolph ridiculed the suggestion, stating that it would allow Borglum to carve "whatever he pleased on the mountain".[24] Borglum accused Randolph of using donations for his own benefit, and spending freely on an expense account.[5] These dissensions became public, and in February 1925, the Association fired Borglum.[33] Randolph stated, as one reason for dismissing the sculptor, that Borglum had taken seven months to design the coin, when, he said, any competent artist could have done it in three weeks.[a][18] He accused Borglum of delaying so that the Association would be embarrassed.[34] According to Freeman, "despite all the points of conflict between Borglum and the committee, it was actually the commemorative coin that ended his career at Stone Mountain."[35]

Upon being dismissed, Borglum wrecked his models for the monument; the Association sought to have him jailed for destruction of property.[33] Borglum was addressing the ladies of the Atlanta chapter of the UDC when his assistant, Jesse Tucker, burst in and hurried him out the door with a minimum of explanation, only moments before a sheriff's deputy arrived to serve the warrant.[36] He left the state, but was arrested in Greensboro, North Carolina, though quickly allowed bail, and the Association abandoned extradition proceedings.[37] Freed, the sculptor soon took up a project in South Dakota, Mount Rushmore.[26] The publicity surrounding these events hurt the Association's fundraising, as did allegations that the Association had misused hundreds of thousands of dollars put aside for the project.[38]

Marketing and distribution

[edit]The Association hired Augustus H. Lukeman as replacement sculptor;[39] all of Borglum's work was eventually blasted away.[40] Despite the dispute with Borglum, the Association proceeded to market the half dollars; it hired New York publicist Harvey Hill to run the campaign.[16] The Association hoped for the opportunity to present the first coin to President Coolidge in person as a means of overcoming the bad publicity; White House officials warily declined, writing that "no good purpose would be served by a formal presentation".[41] The half dollars were officially released on July 3, 1925 (though some were displayed as early as May);[22] they were sold at a price of one dollar.[16] They were sent to 3,000 banks by the Federal Reserve, with the proceeds from sales credited to the Association.[32] White Southerners applauded the piece as symbolizing sectional reconciliation, the federal government paying homage to the South's Confederate heritage.[42]

The coins were to be distributed through banks, and the Federal Reserve System cooperated by moving coins as needed, though at the Association's expense. The Association set up local affiliates, with organizations throughout the South, as well as Oklahoma and the District of Columbia. Each state's governor served as nominal head of the organization within his jurisdiction; on July 20, 1925, at a meeting of the Conference of Southern Governors called for the purpose, they (or their representatives) resolved that the Association allocate sales quotas among the states on the "basis of white population and bank deposits".[43][44] The pieces were to be sold at the price of one dollar, and local organizations were to generate promotions for selling them. The overall drive to sell half dollars was dubbed the "Harvest Campaign"[43][45] and began with the governors' meeting in July 1925. Georgia Governor Clifford Walker told his colleagues that the "South would be eternally disgraced if it failed to accept the challenge" of meeting the sales goal of 2,500,000 coins; nevertheless, the governors devoted little time to the campaign.[44]

Although volunteer enthusiasm was essential to the Association's plans in the Harvest Campaign, it did not rely on it at the higher levels; the state chairs were compensated, both by salary and commission. J.W. Gibbes, clerk of the South Carolina House of Representatives, was hired as that state's executive director; he undertook to sell 100,000 coins and received just under $3,500 in salary and commissions, all paid in 1926. Local volunteers organized Chamber of Commerce luncheons to sell coins throughout the South; chapters of the UDC purchased pieces to present to surviving Civil War veterans.[46] The quota for Florida was 175,000 coins, with each town and city apportioned its share. Often, Kiwanis or Rotary groups underwrote local quotas.[47] Mrs. N. Burton Bass of Atlanta was reported to be the leading seller, once disposing of 233 coins in an afternoon. A series of dance balls honored the UDC members who sold large numbers of pieces. Nevertheless, Hyder and Colbert suggested that there was "a general lack of more ladies such as Mrs. Bass"; many municipalities had trouble finding local chairs.[48] Outside the South, sales were promoted by three professional publicists hired by the Association.[49] To keep public interest high, the Association released Lukeman's conceptions for Stone Mountain, which were on a smaller scale than Borglum's.[50] Lukeman conceived a scaled-down concept, of the three Confederate leaders on horseback.[5] Despite the campaign, sales were slower than expected.[51] In late 1925, the Association offered Northern banks a commission of seven cents a coin; it is uncertain if any took up the offer.[52] The continuing opposition of the GAR to the coins dampened sales in the North,[53] and there was considerable criticism of the coin issue in newspapers.[54]

One means of fundraising that Harvest Campaign administrators decided on was to counterstamp some of the coins for sale at premium prices. The letters and numbers are believed to have been punched by the Association, as they are almost entirely uniform. Some were given a state abbreviation and a number, and were sent to be auctioned in various towns. Gibbes reported that the counterstamped pieces sent to South Carolina sold for an average of $23, ranging from $10 to $110, and recommended that the auctions be preceded with the account of the sale of one in Bradenton, Florida, for $1,300.[55] Which town got which number was the luck of the draw.[56] Others were marked with "U.D.C." and a state abbreviation, together with a number which probably represents a membership or chapter number. These were intended for presentation to members deserving of special honor, such as an outgoing president. They did not sell well, as the Association had alienated many UDC members over the firing of Borglum. The Association also announced a program for sale to the Sons of Confederate Veterans, although whether any coins were sold under this program is unclear, as none have been identified.[57] Pieces marked "G.L." and "S.L." were puzzled over by collectors for many years; A. Steve Deitert in the January 2011 edition of The Numismatist identified the markings as "Gold Lavalier" and "Silver Lavalier". These coins were given to county winners and runners-up in a selling competition for young women.[58]

The Association sold coins through other means. They asked companies to purchase them: the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad [B&O], the Southern Fireman's Fund Insurance Company, the Coca-Cola Company, and a number of banks, purchased thousands of pieces, many of which were given away as promotions.[59] Those outside the South could obtain coins by orders passed through local banks.[60] A bank in St. Louis gave away the half dollars to those who opened an account with at least $5; the B&O used them in making change.[47]

The Association called an end to the Harvest Campaign as of March 31, 1926, most likely because the sales did not justify the continued salary expenses. Coins remaining at banks were to be sent to the Federal Reserve, and any credit balances remitted to the Association. Thereafter, coins were available either through the Association or the Federal Reserve at an increased price of $2. With a price increase and the end to the campaign, sales plummeted. Total sales from the Harvest Campaign were about 430,000 pieces. One exception to the drop in sales was a drive in New York under the sponsorship of Mayor Jimmy Walker, which succeeded in selling 250,000 coins in 1926, though at the original price of one dollar. Bernard Baruch, then a prominent investor and later a counselor of presidents, was honorary chairman of the organizing committee, and personally subscribed for some of the pieces.[60][61]

Aftermath

[edit]

The Atlanta chapter of the UDC in 1927 published a brochure accusing the Association of wrongfully firing Borglum and wasting between a quarter and a half million dollars.[62] An audit of the Association's books was performed in 1928; the examiners found its records in good order, excepting those regarding the Harvest Campaign, which were inadequate. The audit found that for every three dollars of revenue brought in from the half dollars, two were paid out in expenses, a ratio Hyder and Colbert called "incredible".[63] Of the total sum raised by the Association, only 27 cents of each dollar went to the carving.[64] Venable stated that the Stone Mountain monument had "developed into the most colossal failure in history".[62][65]

The Association was discredited by the results of the audit; the Georgia Senate voted to accuse it of gross mismanagement of funds. Randolph resigned when Venable made it clear he would not negotiate an extension of the twelve-year deadline unless he did. The Atlanta lawyer had begun a political career; the scandal finished it. With funds drying up, the Association stopped work on Stone Mountain on May 31, 1928, and when negotiations failed, the Venable family successfully sued to regain the property. Borglum was now a folk hero in Atlanta; he was called upon to return to Stone Mountain in the early 1930s, but busy with Mount Rushmore, he did not. At the time of Borglum's death in 1941, no work was being done on Stone Mountain. The State of Georgia voted funds to purchase Stone Mountain in 1958 and five years later selected Walker Kirkland Hancock as architect. The sculpture, which depicts Lee, Jackson and Davis, and bears only a resemblance to Borglum's original design, was dedicated in 1970.[65][66][67] At 90 feet (27 m) by 190 feet (58 m), it is the largest relief sculpture in the world.[5]

In 1930, Secretary Mellon reported that although no Stone Mountain Memorial half dollars were held by the Mint, it was his understanding that large quantities of the piece were in the possession of banks. Eventually, arrangements were made to return a million half dollars to the Mint for melting. In spite of this, the State of Georgia still had Stone Mountain half dollars for sale at its exhibit at the 1933 Century of Progress Exposition.[60] Many more were dumped into circulation in the 1930s.[5] A quantity of half dollars once owned by Baruch were sold for $3.25 each through a Georgia bank in the 1950s to finance a building in honor of Baruch's mother, a Southerner, in Richmond, Virginia.[68] A total of 1,314,709 Stone Mountain Memorial half dollars were distributed, after deducting those pieces melted.[69]

Due to the large quantities extant, Stone Mountain Memorial half dollars remain inexpensive in comparison with other commemoratives. The 2014 edition of A Guide Book of United States Coins lists the piece at $65 in Almost Uncirculated condition (AU-50) with pieces in near-pristine MS-66 at $335.[69]

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Hyder and Colbert point out that few commemorative coins have been designed in as short a span of time as three weeks. Hyder & Colbert, p. 4

References and bibliography

[edit]- ^ LaMarre, p. 34.

- ^ LaMarre, p. 35.

- ^ LaMarre, pp. 34–35.

- ^ a b Freeman, pp. 56–57.

- ^ a b c d e f Flynn, p. 175.

- ^ a b c LaMarre, p. 36.

- ^ a b c d e f Bowers Encyclopedia, Part 47.

- ^ a b Hyder & Colbert, p. 2.

- ^ Swiatek & Breen, p. 227.

- ^ Freeman, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Freeman, pp. 66, 72.

- ^ Hyder & Colbert, p. 3.

- ^ Freeman, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Freeman, p. 81.

- ^ Hyder & Colbert, pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b c Slabaugh, p. 63.

- ^ Flynn, p. 350.

- ^ a b c d Hyder & Colbert, p. 4.

- ^ Taxay, pp. 75–76.

- ^ a b Freeman, p. 82.

- ^ Taxay, pp. 74–77.

- ^ a b c d Swiatek & Breen, p. 228.

- ^ Taxay, p. 77.

- ^ a b Hyder & Colbert, p. 5.

- ^ a b Freeman, p. 83.

- ^ a b Slabaugh, p. 64.

- ^ Swiatek, p. 177.

- ^ Vermeule, pp. 169–170.

- ^ Bowers Encyclopedia, Part 48.

- ^ Hyder & Colbert, p. 6.

- ^ Flynn, p. 176.

- ^ a b Freeman, p. 99.

- ^ a b c Hale, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Freeman, p. 93.

- ^ Freeman, p. 84.

- ^ Freeman, p. 86.

- ^ "Lukeman is dead; a noted sculptor" (PDF). The New York Times. April 4, 1935. Retrieved March 18, 2013.(subscription required)

- ^ Hale, p. 34.

- ^ Bowers Encyclopedia, Part 49.

- ^ Freeman, p. 111.

- ^ Hyder & Colbert, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Hale, p. 30.

- ^ a b Hyder & Colbert, p. 7.

- ^ a b Freeman, p. 100.

- ^ Swiatek & Breen, p. 229.

- ^ Hyder & Colbert, p. 9.

- ^ a b Jones, p. 396.

- ^ Hyder & Colbert, p. 12.

- ^ Freeman, p. 101.

- ^ Freeman, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Freeman, p. 103.

- ^ Freeman, p. 104.

- ^ Freeman, p. 107.

- ^ Jones, p. 395.

- ^ Swiatek, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Deitert, p. 39.

- ^ Hyder & Colbert, pp. 14–16.

- ^ Deitert, pp. 37–39.

- ^ Swiatek & Breen, pp. 228–229.

- ^ a b c Bowers Encyclopedia, Part 50.

- ^ Freeman, pp. 106–107.

- ^ a b Bowers Encyclopedia, Part 51.

- ^ Hyder & Colbert, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Freeman, p. 119.

- ^ a b Bowers Encyclopedia, Part 52.

- ^ Hyder & Colbert, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Freeman, pp. 116–119.

- ^ Hyder & Colbert, p. 19.

- ^ a b Yeoman, p. 291.

Books

- Flynn, Kevin (2008). The Authoritative Reference on Commemorative Coins 1892–1954. Roswell, Ga.: Kyle Vick. ASIN B001P1OOH8.

- Freeman, David B. (1997). Carved in Stone: A History of Stone Mountain. Macon, Ga.: Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0-86554-547-2.

- Hyder, William D.; Colbert, R.W. (1985). The Selling of the Stone Mountain half dollar. Colorado Springs, Col.: American Numismatic Association (pamphlet with reprint from March 1985 The Numismatist).

- Jones, John F. (May 1937). "The Series of United States Commemorative Coins". The Numismatist. American Numismatic Association: 393–396.

- Slabaugh, Arlie R. (1975). United States Commemorative Coinage (second ed.). Racine, Wis.: Whitman Publishing (then a division of Western Publishing Company, Inc.). ISBN 978-0-307-09377-6.

- Swiatek, Anthony (2012). Encyclopedia of the Commemorative Coins of the United States. Chicago: KWS Publishers. ISBN 978-0-9817736-7-4.

- Swiatek, Anthony; Breen, Walter (1981). The Encyclopedia of United States Silver & Gold Commemorative Coins, 1892 to 1954. New York: Arco Publishing. ISBN 978-0-668-04765-4.

- Taxay, Don (1967). An Illustrated History of U.S. Commemorative Coinage. New York: Arco Publishing. ISBN 978-0-668-01536-3.

- Vermeule, Cornelius (1971). Numismatic Art in America. Cambridge, Mass.: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-62840-3.

- Yeoman, R.S. (2013). A Guide Book of United States Coins 2014 (67th ed.). Atlanta, Ga.: Whitman Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7948-4180-5.

Other sources

- Bowers, Q. David. "Chapter 8: Silver commemoratives (and clad too), Part 47". Commemorative Coins of the United States: A Complete Encyclopedia. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- Bowers, Q. David. "Chapter 8: Silver commemoratives (and clad too), Part 48". Commemorative Coins of the United States: A Complete Encyclopedia. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- Bowers, Q. David. "Chapter 8: Silver commemoratives (and clad too), Part 49". Commemorative Coins of the United States: A Complete Encyclopedia. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- Bowers, Q. David. "Chapter 8: Silver commemoratives (and clad too), Part 50". Commemorative Coins of the United States: A Complete Encyclopedia. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- Bowers, Q. David. "Chapter 8: Silver commemoratives (and clad too), Part 51". Commemorative Coins of the United States: A Complete Encyclopedia. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- Bowers, Q. David. "Chapter 8: Silver commemoratives (and clad too), Part 52". Commemorative Coins of the United States: A Complete Encyclopedia. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- Deitert, A. Steve (January 2011). "Unraveling the mystery of the counterstamped half dollars". The Numismatist. Colorado Springs, Col.: American Numismatic Association: 36–39.

- Hale, Grace Elizabeth (Spring 1998). "Granite stopped time: The Stone Mountain memorial and the representation of white Southern identity". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. 82 (1). Lincoln, Neb.: Georgia Historical Society: 22–44. JSTOR 40583695.

- LaMarre, Tom (June 2002). "The Many Faces of Stone Mountain". Coins. Iola, Wis.: Krause Publications, Inc.: 34–36, 38, 40, 69.