Third Battle of Winchester

| Third Battle of Winchester (Battle of Opequon) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

Battle of Opequon, chromolithograph by Kurz & Allison, 1893. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 40,000 | 15,514 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 5,018 | 4,015 | ||||||

The Third Battle of Winchester, also known as the Battle of Opequon or Battle of Opequon Creek, was an American Civil War battle fought near Winchester, Virginia, on September 19, 1864. Union Army Major General Philip Sheridan defeated Confederate Army Lieutenant General Jubal Early in one of the largest, bloodiest, and most important battles in the Shenandoah Valley. Among the 5,000 Union casualties were one general killed and three wounded. The casualty rate for the Confederates was high: about 4,000 of 15,500. Two Confederate generals were killed and four were wounded. Participants in the battle included two future presidents of the United States, two future governors of Virginia, a former vice president of the United States, and a colonel whose grandson, George S. Patton, became a famous general in World War II.

After learning that a large Confederate force loaned to Early left the area, Sheridan attacked Confederate positions along Opequon Creek near Winchester, Virginia. Sheridan used one cavalry division and two infantry corps to attack from the east, and two divisions of cavalry to attack from the north. A third infantry corps, led by Brigadier General George Crook, was held in reserve. After difficult fighting where Early made good use of the region's terrain on the east side of Winchester, Crook attacked Early's left flank with his infantry. This, in combination with the success of Union cavalry north of town, drove the Confederates back toward Winchester. A final attack by Union infantry and cavalry from the north and east caused the Confederates to retreat south through the streets of Winchester.

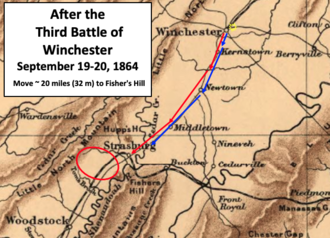

Sustaining significant casualties and substantially outnumbered, Early retreated south on the Valley Pike to a more defendable position at Fisher's Hill. Sheridan considered Fisher's Hill to be a continuation of the September 19 battle and followed Early up the pike, where he defeated Early again. Both battles are part of Sheridan's Shenandoah Valley campaign that occurred in 1864 from August through October. After Sheridan's successes at Winchester and Fisher's Hill, Early's Army of the Valley suffered more defeats and was eliminated from the war in the Battle of Waynesboro, Virginia on March 2, 1865.

Background and plan

[edit]

In August 1864, the American Civil War was in its fourth year, and the exploits of Confederate Lieutenant General Jubal Early caused considerable consternation among leaders of the federal government of the United States.[note 1] Major General Philip Sheridan, commander of the new Middle Military Division, faced constant pressure to attack Early, but Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant warned Union leaders on August 12 that two divisions of infantry had joined Early, and that Sheridan "must be cautious and act now on the defensive" until Grant's actions near Richmond would cause those units to return to the Richmond area.[6] The impending presidential election of 1864 made it necessary to avoid any military disaster that might hamper the re-election of President Abraham Lincoln.[7] Sheridan kept his troops between Early's army and Washington, and fought several small battles—including the Battle of Berryville that ended September 4. After that battle, Early withdrew during the night to the west side of Opequon Creek between Berryville and Winchester, Virginia[8]Sheridan's troops kept their same positions for the next few weeks, with daily cavalry probes including the capture of the 8th South Carolina Infantry Regiment by a cavalry brigade led by Brigadier General John B. McIntosh.[9] Sheridan's tentativeness caused Early to believe Sheridan was a timid commander.[7]

Sheridan's plan

[edit]

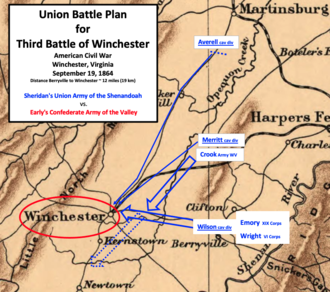

During September 1864, Sheridan sought information about Early's troop strength. His scouts discovered Thomas Laws, a slave with a permit to enter Winchester to sell produce, who agreed to carry messages.[10] A schoolteacher named Rebecca Wright, who was living in Winchester, agreed to provide information on Early's troops.[10] From a message written on September 16, Sheridan learned from Wright through Laws that a division of infantry and battalion of artillery, commanded by Major General Joseph B. Kershaw, had left the area to rejoin General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia near Richmond or Petersburg.[11] Given the information, Sheridan planned to send his infantry to Newtown on the next day, which would prevent a retreat south by Early. His plan was delayed when Grant directed Sheridan to meet him at Charlestown, and upon returning he changed his plan to accommodate Early sending two divisions to Martinsburg, West Virginia.[12]

In Martinsburg, Early became aware of Grant's visit on the morning of September 18, and sent one division to Bunker Hill (slightly north of the halfway point between Winchester and Martinsburg) and the other division (with Early) further south to Stephenson's Depot on the north side of Winchester.[13] Sheridan's final plan was to have cavalry divisions led by Brigadier General Wesley Merritt and Brigadier General William W. Averell attack from the north. From the east, a cavalry division led by Brigadier General James H. "Harry" Wilson would lead two infantry corps from Berryville eastward to attack Early's vastly-outnumbered force between Opequon Creek and Winchester. Crook's two divisions would be held in reserve until later, when they would occupy the Valley Pike on the south side of Winchester.[14][note 2]

Opposing forces

[edit]Union army commanded by Philip Sheridan

[edit]

The Union force in the Third Battle of Winchester was the Army of the Shenandoah, which was recreated August 1, 1864, and commanded by Major General Philip Sheridan. At its creation, the army had three objectives. First, it was to drive Early's army away from the Potomac River region and lower (northern) Shenandoah Valley, and pursue it southward. Second, it would destroy the valley's capacity to provide Lee's Army of Northern Virginia with food and other goods. Third, it was to disrupt the Virginia Central Railroad.[16]

In mid-September, the Army of the Shenandoah had ten divisions plus artillery units, totaling to about 40,000 men.[16]

- VI Corps had three divisions and an artillery brigade, and was commanded by Major General Horatio Wright. His fighters were considered reliable veterans.[17] Wright's artillery consisted of six four-gun batteries of Napoleons and 3-inch rifles, which totaled to half of the artillery assigned to Sheridan's infantry.[18]

- XIX Corps, consisting of two divisions, was commanded by Brigadier General William H. Emory.[19] Each of his divisions had its own artillery, plus more artillery was held in reserve.[16] The XIX Corps were considered behind the VI Corps in discipline and efficiency.[20]

- The Cavalry Corps, consisting of three divisions and a section of horse artillery, was commanded by Brigadier General Alfred Torbert.[16] Fifteen regiments of the cavalry were completely armed with the carbine version of the Spencer repeating rifle, which held seven cartridges in its magazine. Three more regiments were partially armed with the rifle version of the weapon, an advantage over single-shot firearms.[21][22]

- The Army of West Virginia functioned as an infantry corps in Sheridan's Army of the Shenandoah, and is sometimes incorrectly identified as the VIII Corps.[note 3] It was commanded by Brigadier General George Crook, and had two divisions plus an artillery brigade.[25] Crook was a professional soldier and Sheridan's roommate at West Point, and had a good grasp of military tactics.[26] One of Crook's brigade commanders, Colonel Rutherford B. Hayes, later became President of the United States.[27] A member of Crook's staff, Captain William McKinley, also became president two decades after Hayes.[28][29]

Confederate army commanded by Jubal Early

[edit]

The Confederate force was the Army of the Valley, which was created in June 1864 and commanded by Lieutenant General Jubal Early. This army was a detachment of the Army of Northern Virginia's Second Corps, and consisted of six divisions plus artillery.[30] Its purpose was to protect the Shenandoah Valley, which was a major source of food for eastern Confederate armies. Another objective was to threaten the Union's capital of Washington, and cause it to devote resources to protect the capital and northern states—which would relieve some of the pressure on the Army of Northern Virginia near the Confederate capital of Richmond.[31]

The division commanded by Kershaw was loaned to Early, but returned to the Richmond-Petersburg area over 120 miles (190 km) away. Without Kershaw's Division of about 3,400 men, Early's army had 15,514 men as of September 10, 1864.[32] The National Park Service uses a count of 15,200 for the battle.[33] The army had a large infantry corps and a cavalry corps, and many of the regiments were from Virginia and North Carolina.[34]

- Breckinridge's Corps was commanded by Major General John C. Breckinridge, who had been vice president of the United States from 1857 to 1861 as part of the administration of President James Buchanan.[35] His corps had four infantry divisions and an artillery unit.[34] Among his brigade commanders was Colonel George S. Patton, whose grandson became a well-known general in World War II.[36]

- The Cavalry Corps was commanded by Major General Fitzhugh Lee, a future governor of Virginia who was a grandson of Henry "Light-Horse Harry" Lee (of American Revolution fame) and nephew of the Army of Northern Virginia commander Robert E. Lee[37][38] The cavalry had two divisions, and each had its own horse artillery[34]

Union cavalry strikes first

[edit]Wilson's 3rd Cavalry Division advances from east

[edit]

On September 19, 1864, Wilson's Division began moving west at 2:00 am from Berryville on the Berryville Pike with McIntosh's Brigade as the vanguard.[39] The 1st Connecticut Cavalry Regiment departed hours earlier and secured Limestone Ridge, which overlooked the Spout Spring ford of Opequon Creek at the Berryville Pike.[40] That point is about five miles (8.0 km) from Winchester, and the road west of the crossing runs through a narrow ravine or small canyon (a.k.a. Berryville Canyon) for several miles (over 3.2 km).[41] Two cavalry regiments, the 2nd New York followed by the 5th New York, led the initial advance across Opequon Creek.[42] They pursued the 37th Virginia Cavalry Battalion on the pike to the west end of Berryville Canyon, where the Virginians fled past pickets from the 23rd North Carolina Infantry Regiment.[43] The North Carolinians fell back several hundred yards (about 275 m) beyond the west end of Berryville Canyon, and joined the rest of their brigade as their commander sent a courier to division commander Major General Stephen Dodson Ramseur.[44]

McIntosh attacked the high ground with his lead regiments armed with repeating rifles. Lieutenant Colonel William P. Brinton, commanding the 18th Pennsylvania Cavalry Regiment, led a charge that captured an important Confederate breastworks.[43] The Confederates regrouped and recaptured the breastworks, shooting Brinton's horse and capturing Brinton, who escaped that evening.[45] McIntosh personally led men from the 2nd Ohio Cavalry Regiment, some dismounted, and again captured the breastworks.[43] Wilson reported that with the breastworks "securely in our possession, the infantry were enabled to form at leisure and to deliver battle with every prospect of success."[46] The fighting reached a stalemate as Ramseur rallied his men and brought in reinforcements, while Wilson deployed his artillery. His other brigade, commanded by Brigadier General George H. Chapman, deployed to the north along a line that would eventually be occupied by the XIX Corps.[43] Sheridan rode behind Wilson's Cavalry Division, leaving Wright to direct the movement of 24,000 infantry men from the VI and XIX Corps using the Berryville Pike from Berryville to Winchester.[47] Wright's VI Corps, who arrived at the beginning of Berryville Canyon about 5:00 am, moved a baggage train and artillery into the narrow canyon before the fighters from Emory's XIX Corps could enter. A combination of ambulances returning from the front with McIntosh's wounded plus Wright's wagons moving toward the front caused a massive traffic jam. Emory's XIX Corps did not enter the canyon until 9:00 am.[47]

Merritt's 1st Cavalry Division advances from northeast

[edit]

Merritt's 1st Cavalry Division also began moving at 2:00 am on September 19. The division left camp from Summit Point, West Virginia, which was on the Winchester and Potomac Railroad about seven miles (11 km) north of Berryville. At the time, the railroad was out-of-service. Merritt and Cavalry Corps commander Torbert rode with Colonel Charles R. Lowell and his Reserve Brigade, which led the advance.[43] The Second Brigade, led by Brigadier General Thomas Devin, covered the rear. The First Brigade, led by Brigadier General George Armstrong Custer, was about one mile (1.6 km) north and advanced independently. The brigades reached fords on Opequon Creek before daybreak, where they met their first serious opposition.[48][note 4]

On the other side of the creek guarding the fords were two brigades from Confederate Brigadier General Gabriel C. Wharton's Infantry Division (a.k.a. Breckinridge's Division), plus Brigadier General John McCausland's Cavalry Brigade commanded by Colonel Milton J. Ferguson. A third brigade was held in reserve at Stephenson's Depot. Confederate pickets exchanged shots with Lowell's dismounted cavalry regiments. The fighting was a stalemate until the 2nd U.S. Cavalry Regiment charged across the creek and up its banks, which drove the Confederates to a breastworks one and a half miles (2.4 km) back.[43] Further to Lowell's right (north), Custer's Brigade struggled to gain control of Locke's Ford. However, Lowell's 2nd U.S. Cavalry moved toward the right flank of Custer's opposition, causing them to withdraw before their line of retreat was cut off. By 7:00 am, Lowell and Custer were safely across the Opequon, while Devin's Brigade remained in reserve on the creek's east side.[43]

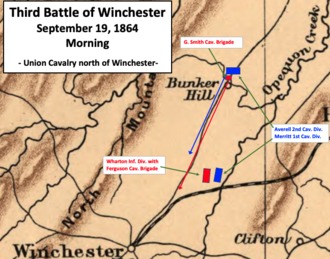

Averell's 2nd Cavalry Division advances from north

[edit]Averell's 2nd Cavalry Division did not leave their camps until 5:00 am. His First Brigade, led by Colonel James M. Schoonmaker, departed from Martinsburg. Averell's Second Brigade, led by Colonel William H. Powell, departed two miles (3.2 km) east of Opequon Creek at Leetown, West Virginia.[note 5] Averell rode with Powell, and they linked with Schoonmaker on the Martinsburg Pike slightly north of Darkesville after finding no opposition at the Burns Ford crossing of the creek.[43]

Averell and his brigade commanders were familiar with the area, having fought on the north side of Winchester in the Battle of Rutherford's Farm, and on the south side in the Second Battle of Kernstown.[51] Near Darkesville around 8:30 am, Averell's scouts encountered pickets from the 23rd Virginia Cavalry Regiment, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Charles T. O'Ferrall—a future U.S. congressman and governor of Virginia.[43][52] The pickets soon fled south, choosing to not confront Averell's 2,500–man division.[43]

Morning: infantry gets ready and cavalry repositions

[edit]Union and Confederate infantry positions before attack

[edit]

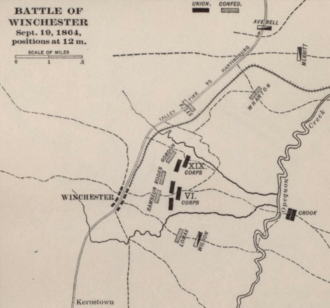

Union infantry positioning prior to the infantry attack had Wright's VI Corps on the left and Emory's XIX Corps on the right. The VI Corps was mostly in place by 9:00 am, and was about two miles (3.2 km) from Winchester.[53] Brigadier General George W. Getty's 2nd Division was on the left with Abrams Creek (a.k.a. Abrahams Creek) on its left, while Brigadier General James B. Ricketts's 3rd Division was on the right with Ash Hollow on its right.[47] Brigadier General David Allen Russell's 1st Division was held in reserve. The two divisions in Emory's XIX Corps, delayed by congestion on the Berryville Pike, did not get into position until 11:00 am. They were positioned north of the Berryville Pike between Ash Hollow and Red Bud Run. Brigadier General Cuvier Grover's 2nd Division was Sheridan's largest, and it had four brigades stacked on the front. Brigadier General William Dwight's 1st Division was held in reserve. Sheridan kept Crook's two divisions of the Army of West Virginia, labeled as the VIII Corps on some maps, in reserve at Opequon Creek.[47]

Once Ramseur and McIntosh began fighting, Lee sent his cavalry division, commanded by Brigadier General Williams Carter Wickham, to the north side of Red Bud Run where they faced south. He also sent Major James Breathed's Battalion of horse artillery, which protected the ground in front of the divisions of Major General John B. Gordon and Major General Robert E. Rodes. Lee supervised the artillery, and his men skirmished across the creek with Chapman's Brigade from Wilson's Division until the XIX Corps got into position.[54] The delay in positioning Union infantry enabled Early to rush two Confederate infantry divisions from north of Winchester to positions adjacent to Ramseur, which prevented Sheridan from overwhelming Ramseur's single division. Gordon's Division left Bunker Hill and was deployed on Ramseur's left close to the Hackwood Farm on the south side of Redbud Run. Rodes' Division was deployed between Ramseur and Gordon. Ramseur's position was one mile (1.6 km) east of Winchester near a barn on a farm owned by Enos Dinkle.[53] North of Winchester, Wharton's Division of infantry and two cavalry brigades faced north and east. Skirmishers for both sides were extended before the Union infantry attack, and artillery was also utilized.[47][note 6]

Union cavalry

[edit]

Around 8:00 am, part of the VI Corps arrived at the west end of the canyon and relieved Wilson's cavalry.[46] Most of Wilson's Division moved south of the Berryville Pike to Senseny Road beyond Abrams Creek. Here they rested and replenished ammunition. Their location was on the extreme left of the Union infantry line, about a one-half mile (0.80 km) south of Getty's left flank. They were the closest Union force to Early's Valley Pike escape route south. A few skirmishers remained to the right until they were replaced with the XIX Corps.[47]

From the north, Averell's Cavalry Division moved south on the Martinsburg Pike until the division was slightly north of Bunker Hill, which is about 12 miles (19 km) north of Winchester. They encountered Brigadier General John D. Imboden's cavalry brigade of about 600 men, commanded by Colonel George H. Smith.[43] At 10:00 am, Averell had Weir's Battery L commence firing and the Confederate brigade quickly fled south toward Stephenson's Depot. South of Bunker Hill, a section of the Confederate Lewisburg Artillery, using two rifled guns sent by Breckinridge to assist Smith, slowed Averell's advance. Averell responded with all six of his artillery pieces, driving the Confederates away. He continued moving south along the pike, getting closer to Stephenson's Depot and the rear of Wharton's Confederate Infantry Division.[43]

Merritt's Cavalry Division was held for hours at Wharton's second position, which was behind stone walls.[58] Eventually, the Confederates moved south, and Merritt followed slowly. He attacked Wharton's front around 11:00 am near Brucetown, but did not press forward since it was better to hold the enemy infantry away from Winchester and keep them out of the Union infantry attack that would happen soon.[43]

Union infantry attacks from east

[edit]

The two Union infantry corps attacked almost simultaneously, Wright's VI Corps at 11:40 am and Emory's XIX Corps at 11:45 am.[59][note 7] Both sides had already sent forward skirmishers, and Wright was supported by artillery. While the Union infantry began their attack, Wilson's cavalry also probed the area east of Senseny Road, but was too far away to support the VI Corps' left.[61] For the first 30 minutes, Wright caused Ramseur to retreat on the Berryville Pike, and Emory had similar success with one of his brigades against Gordon.[47]

Wright's VI Corps attack: Getty and Ricketts

[edit]Wright had two divisions and four batteries at the front, and one division in reserve.[62] His force outnumbered the Confederate opposition, Ramseur's Infantry Division assisted by cavalry, by almost four to one. However, the uneven terrain, especially the ravines, made it difficult for Wright's men to see their enemy.[47] Ricketts' 3rd Division, on the right, was guided by the Berryville Pike, which moved to the left and caused a gap between Ricketts and the XIX Corps on his left. The division was hit hard by Confederate artillery, causing a pause in forward movement. On the left, Getty's 2nd Division advanced slowly while it underwent artillery fire from two sides. A battery belonging to Lieutenant Colonel William Nelson's battalion was in front, while a section of Lomax's horse artillery delivered enfilading fire from the distant left (south). Ricketts resumed advancing, and the brigade commanded by Colonel J. Warren Keifer moved beyond supporting brigades and past Ramseur's left flank, causing a Confederate retreat from the Dinkle Barn toward Winchester. The time was 12:10 pm, and Ramseur was almost overwhelmed.[47]

Emory's XIX Corps attack

[edit]

Emory's XIX Corps used the brigades of Grover's 2nd Division to face Gordon's Division.[63] The terrain in their front included a First Woods, Middle Field, and a Second Woods.[note 8] The Middle Field was an open field about 600 yards across.[60] Grover had initial success in pushing the enemy back. However, the success caused the front brigades to move forward too fast, and commanders had trouble restraining their enthusiastic men. On the left, Colonel Jacob Sharpe's Third Brigade had gaps on its left (VI Corps) and right. Before the gap could be filled, Gordon attacked with a brigade backed by artillery.[66] Sharpe's replacement, Lieutenant Colonel James P. Richardson, was also wounded, as were all but one of the regimental commanders.[67]

On the right, Brigadier General Henry Birge's First Brigade pushed through the Middle Field and Second Woods, then chased Gordon's men beyond the Second Woods—leaving supporting Union brigades behind. Birge's men came upon seven Confederate artillery pieces that were hidden in haystacks. The Confederate gunners waited until retreating Confederate soldiers passed them, and then fired double loads of canister at close range into the surprised Union brigade. This devastated Birge's troops about the same time that a portion of Rodes' Confederate Division arrived. Although Rodes was fatally shot, his brigade commanders pressed the attack on Birge's men, causing them to retreat. Falling back to the Middle Field, the Union troops became a target for Lee's artillery and sharpshooters located north of Red Bud Run.[47] Assistance from supporting units was ineffective. The division was done fighting, and Birge's Brigade had over 500 casualties. Only one other Union brigade had more than 350 casualties that day.[68]

Emory used Dwight's 1st Division to stop the retreats of all four of the 2nd Division brigades. Dwight sent his First Brigade, commanded by Colonel George Lafayette Beal, to the right; and Emory worked with Dwight's Second Brigade on the left. Much of the fighting by Beal's Brigade was done by the 114th New York Infantry Regiment, whose 185 casualties were more than any other Union regiment.[68] On the left, the 8th Vermont and the 12th Connecticut were the two infantry regiments that did most of the fighting.[69] The XIX Corps attack was stopped around 1:00 pm with heavy casualties for both sides, and a small victory for Gordon.[70] The 1st Division of the XIX Corps then transitioned to the defense.[71]

Russell, Edwards, and Upton save the VI Corps

[edit]

Ricketts' Division moved beyond the Dinkle Barn, with Keifer's Brigade on the right advancing beyond his support on either flank. As Keifer attempted to capture Confederate batteries, a brigade from Rodes' Division attacked from the Union front and right. Keifer was routed, and his men retreated in wild disorder. This assistance from Rodes ended Ramseur's retreat and revitalized his men.[72] Soon the remaining portion of Rickett's Division was retreating, and the retreat spread to Getty's Division. The Confederates regained control of Dinkle Barn and pressed forward at the gap between the two Union corps. Union Colonel Charles H. Tompkins directed artillery on both the north and south side of the Berryville Pike to assist both corps.[72]

Colonel Oliver Edwards's Third Brigade of Russell's 1st Division of the VI Corps used the 37th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, armed with Spencer repeating rifles, to stop the Confederate advance. At that time, Russell brought up more regiments from Edwards' Brigade and they were joined by two regiments from Ricketts' Division. As Russell ordered Edwards to attack, he was shot and then killed by a shell fragment.[72] Edwards superintended movements until Brigadier General Emory Upton was able to take command.[73] All three of Russell's brigades worked to stop the Confederate bulge in the line. Upton, in person, led his brigade in the capture of a portion of a regiment from North Carolina—including its colonel.[74] The leadership of Russell, Edwards, and Upton re-established the Union infantry line and caused most of the 2,000 to 3,000 Union men who had fled to the rear to return to the front[75] Wright believed the restoration of the Union line was the "turning point in the conflict".[76] It was after 1:00 pm, and Russell's 1st Division restored the infantry line in about 30 minutes of fighting.[77]

Early shifts his forces

[edit]

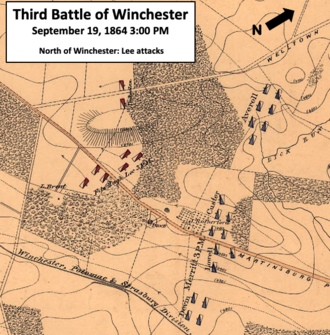

At 12:30 pm, Averell's Division was getting closer to Stephenson's Depot, and Merritt's brigades commanded by Lowell and Custer were two miles (3.2 km) east of the depot facing Wharton's (Breckinridge's) Division.[78] Breckinridge was informed by a messenger from Early that he was needed in Winchester and should retreat toward the Valley Pike before Averell arrived behind him.[79] Breckinridge dismounted the 22nd Virginia Cavalry regiment to Custer's front while his infantry covertly retreated through a woods.[79] Arriving at Stephenson's Depot, Breckinridge found Averell pushing back Smith's Cavalry Brigade. Breckinridge deployed and drove Averell about one mile (1.6 km) north of the depot. Averell countered with his artillery, but was content with an artillery duel while sending scouts to search for Merritt's cavalry.[79] During this time, Patton's Brigade withdrew from Charlestown Road and rejoined Breckinridge's Division. Patton deployed in the woods near the railroad line, and covered the Confederate retreat up the line toward Winchester. With Patton gone, only Smith's dismounted cavalry and a few cannons remained to cover Stephenson's Depot.[79] A captain from Rodes Infantry Division noted in his diary that "after the withdrawal of Breckinridge's Division, the disasters began".[78]

Around 1:00 pm, Wilson's cavalry division probed Lomax's Confederate cavalry at Early's right flank south of Abrams Creek along the Senseny Road.[79] Early responded by moving Wickham's Cavalry Brigade, commanded by Colonel Thomas T. Munford, from the north side of Red Bud Run to south of Abrams Creek.[78] A two-gun battery commanded by Captain John Shoemaker, and a cavalry brigade commanded by Lieutenant Colonel William Thompson, were also shifted to Early's right.[79]

To strengthen his left, Early put Lee in charge of all cavalry north of Red Bud Run.[78] He also ordered Breckinridge to detach Patton's Brigade to assist Lee, and Lee brought most of a cavalry brigade commanded by Colonel William Payne with a four-gun battery of horse artillery to the Martinsburg Pike. Lee moved his men to a pine forest on Rutherford's Farm near the pike.[79]

Torbert continues south

[edit]

At 1:30 pm, Torbert ordered Merritt's Division to advance.[79] Devin's Brigade crossed the Opequon around 2:00 pm and proceeded on the road toward Stephenson's Depot.[80] Further to the right, Custer's Brigade, which was deceived by Breckinridge and Wharton, moved cross-country toward Stephenson's Depot. Lowell's Brigade also moved cross-country, between Devin and Custer. Devin confronted part of Ferguson's Cavalry Brigade on Charlestown Road about one mile (1.6 km) from the Martinsburg Pike, and his two lead regiments chased Ferguson across the road's bridge over the railroad line. This blocked the withdrawal of Patton's Brigade from Stephenson's Depot, but Patton drove Devin off the road and continued south along the rail line. While Devin's Brigade was reorganizing, two of Smith's three regiments at the depot attacked and sent Devin into a short retreat. Devin counter-attacked, and soon Smith's Brigade was riding south on the pike behind Ferguson's men.[81]

South of Stephenson's Depot, Merritt's and Averell's divisions linked to form a large force of five brigades.[58] They passed the Charlestown Road around 2:00 pm, but advanced slowly with their horses at a walk.[79] At the same time, the Confederate cavalry brigades of Ferguson and Smith regrouped on the pike about one mile (1.6 km) south from their confrontation with Devin. Here, at a thick pine forest near the Rutherford Farm, they joined Lee with Payne's Cavalry Brigade and artillery.[82] Lee also had the unexpected assistance of Vaughn's Cavalry and Mounted Infantry Brigade, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Onslow Bean, which returned over difficult terrain around Little North Mountain after destroying a B&O Railroad bridge over Back Creek.[79]

Crook joins the battle

[edit]

Crook's two infantry divisions began moving to the front around 1:00 pm.[83] Crook's 6,000 men would be protecting the extreme right of the XIX Corps instead of his preference of advancing to the extreme left and occupying the south side of Winchester.[84] Colonel Joseph Thoburn arrived at the front around 2:00 pm with the First and Third brigades of his 1st Division, while his Second Brigade remained with the supply wagons on the east side of Opequon Creek. Colonel Isaac H. Duval's 2nd Division followed. Crook moved his men to an open field behind (east of) the First Woods, and Dwight's 1st Division of the XIX Corps was fighting while the 2nd Division of the XIX Corps was in disarray.[83] After surveying the situation and conferring with Dwight, Crook sent Thoburn's Division forward on the south side of Red Bud Run to where the First Woods meets the Middle Field, while Crook went with Duval's Division north toward Red Bud Run.[83]

Crook's orders were to protect the XIX Corps' right flank, but he decided his fresh troops could be aggressive instead of simply holding in a defensive position. At the beginning of the battle, he hoped to move his army around Early's right to the south side of Winchester and cut off Early's route of retreat. That option was now gone, but he believed he could move around Early's left (Gordon, north side of Winchester) and relieve the pressure on the XIX Corps.[note 9] Crook and Duval's Division crossed Red Bud Run, bringing du Pont's artillery brigade.[87] They moved west and came upon several companies from the 153rd New York Infantry Regiment of the XIX Corps, who had been sent by Dwight to the north side of the creek. This small battalion combined with sharpshooters from the 23rd Ohio Infantry Regiment to drive away Confederate sharpshooters from Wickham's Brigade that Lee had left behind, and also drove away the remaining guns from Lee's artillery. Crook was now unopposed on the north side of Red Bud Run, and Union troops in the Middle Field would not be subjected to enfilading fire from the north.[83] Du Pont's 18 cannons were set up on the west side of the Huntsberry Farm, which put the Middle Field, Second Woods, and Hackwood House within their range.[87]

Lee attacks Torbert

[edit]

About 3:00 pm, Torbert had Averell and Merritt moving south toward Winchester in parade formation near the Martinsburg Pike, with Merritt on the left and Averell on the right.[77] They rode through an open field toward a wooded area close to the Rutherford Farm. Waiting in the pine woods was Lee's outnumbered cavalry force, while Patton's infantry and artillery remained further south.[88] Northwest of Lee, Bean's Cavalry Brigade waited in the woods on the Welltown Road.[79] Lee attacked Devin's Brigade on Merritt's left and drove back the Union soldiers about three-quarters mile (1.2 km) toward the Carter Farm. On Averell's right, Bean had similar initial success against Schoonmaker's Brigade.[79]

Devin and Custer struck back at Lee's cavalry using their sabers—a weapon many of the southerners did not have.[79] On Averell's left, Powell sent a portion of the 2nd West Virginia Cavalry Regiment into the woods on his left, where they found Confederate cavalry facing the opposite direction toward Custer. Making use of their 7-shot carbines, the 2nd West Virginia caused the Confederates to run in panic.[89] By that time, Bean was also retreating from Schoonmaker. Lee's men retreated south on the east side of the Martinsburg Pike to near the headwaters of Red Bud Run, but Merritt's men scattered them. Lee was unable to regroup his men until they fell back behind Patton's infantry along the rail line.[79]

Crook's army leads mid-afternoon attack

[edit]Duval and Thoburn attack

[edit]

Crook and Duval's Division marched beyond the Second Woods (on north side of Red Bud Run), and faced south. At 3:00 pm they charged across the creek supported by du Pont's guns.[87] The Confederates responded with the brigade of Colonel Edmund N. Atkinson and Lieutenant Colonel Carter M. Braxton's guns.[83] Hayes' First Brigade went after Braxton only to discover that this end of Red Bud Run was swampy and difficult to cross. Hayes and the 23rd Ohio Infantry were able to get to the other side, but other regiments sought better places to ford the creek.[83] Braxton moved his artillery before Hayes could get out of the mud, and the commander of Duval's Second Brigade, Colonel Daniel D. Johnson, was seriously wounded near the edge of the swamp. Adding to Duval's problems, Patton's Brigade left Lee's cavalry and deployed behind a stone wall to assist Atkinson.[83]

Thoburn's 1st Division heard the noise from Duval's charge and made a charge of their own from the First Woods westward along the south side of Red Bud Run.[90] Near the center of the Middle Field, it received volleys from Gordon's Division and from Battle's Brigade of Rodes' Division. Battle's Brigade was now under command of Colonel Samuel B. Pickens, since Battle had assumed command of the division after Rodes' death.[83] The portion of Atkinson's Brigade that had turned to face Duval received enfilading fire from Thoburn. Confronted on two sides, Atkinson's Brigade began falling back to the edge of the Second Woods. Gordon eventually moved his division out of the Second Woods to a stone wall closer to Winchester. Pickens was wounded and Colonel Charles M. Forsyth assumed command of his brigade. Battle ordered a fall back toward Winchester, which began a disorderly retreat.[83]

VI Corps advances

[edit]

When Thoburn started the 3:00 pm attack, Sheridan attempted to get more of his army to join in. Upton, now commanding the VI Corps' 1st Division, got the news first and focused his attention on enemy infantry in the South Woods.[note 10] He used Company C of the 65th New York Infantry Regiment, the 37th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, and the 2nd Rhode Island Infantry Battalion—all armed with repeating rifles—to drive off two brigades from Rodes' Division.[92] The other portion of Upton's Division was led by Edwards, who faced two Confederate brigades with artillery support on the far (west) end of the Dinkle Farm.[92] The remaining portion of Wright's VI Corps was still reorganizing at 3:40 pm, as Ricketts' Division and Warner's Brigade from Getty's Division were in considerable disarray.[92]

Sheridan rode past the VI Corps infantrymen inspiring them to attack, and they began to advance on both sides of the Berryville Pike. By 4:30 pm, Edwards' men pushed Grimes' Brigade back to the Baker House.[92] Ramseur's men could hear the fighting on their left, and could see stragglers from Gordon's and Rodes/Battle's Divisions retreating. The withdrawal of Grimes and pressure from the other two divisions of the VI Corps forced Ramseur to fall back. As Ramseur began another retreat, he lost a brigade commander when a cannon shell burst killed Brigadier General Archibald C. Godwin.[92] Confederate artillery from Nelson in front and Lomax from the south became the biggest obstacle to the Union advance.[92]

Cavalry attacks from southeast and north

[edit]

Wilson's Division joined the afternoon general assault from the southeast. McIntosh's Brigade had been the vanguard for the whole day, but McIntosh was severely wounded while personally leading a dismounted charge close to the Senseny Road.[93] The wound was severe enough that his leg was amputated below the knee.[46] One historian wrote that "the elimination of McIntosh and his leadership severely hindered the usefulness of Wilson's division".[94] Wilson's other brigade commander, Chapman, was disabled for several hours after his sword belt was struck by a bullet. Chapman's Brigade was temporarily commanded by Colonel William Wells, who pushed Confederate cavalry back beyond Abram's Creek around 4:00 pm, but was repelled by artillery.[95]

While Crook's 2nd Infantry Division was facing Patton, Devin's Cavalry Brigade attacked Patton's left using sabers. In fierce fighting, Devin captured 300 men and all three battle flags from Patton's regiments.[83] Confederate artillery located further south fired into the mass of fighters—hitting friend and foe, but stopping Devin.[83] With Patton driven back, Crook captured the Second Woods. The soldiers from Patton's Brigade that were not captured or killed reformed closer to Winchester behind a stone fence where Gordon had already reformed his division perpendicular to the pike. By now, Gordon's Division and the brigades of Patton and Battle had all experienced significant losses. Hundreds of men from these brigades did not rally at the stone fence, but instead retreated into Winchester.[83] Patton was mortally wounded and captured in Winchester while trying to rally remnants of his brigade.[96]

After Crook gained control of the Second Woods, Averell's cavalry aggressively advanced west of the pike. Using a dismounted squadron from the 1st New York Cavalry Regiment with mounted troopers from Powell's and Schoonmaker's brigades, Averell captured a cannon and 80 men.[83] Next came the capture (and then abandonment) by Schoonmaker of a small fort known as the Star Fort—an action that resulted in Schoonmaker being awarded the Medal of Honor.[97][98] On Averell's left, Powell and Custer attacked the remnants of Payne's and Ferguson's cavalries near the Martinsburg Pike. The two Confederate units fled into Winchester, causing panic in the town. Though repulsed by about 300 men Confederate officers rounded up in town, some of Custer's and Powell's men fired several volleys down the town's northern streets.[83]

With Merritt getting closer to Winchester, Early sent Smith's and Colonel Augustus Forsberg's brigades from Breckinridge's Division to guard the pike.[83] They deployed about 1,500 men behind a stone wall south of the regrouping remnants of Gordon's and Patton's forces, and were aided by batteries from Braxton's and Major William McLaughlin's battalions. The Confederate artillery forced Merritt back about 1,000 yards (914.4 m), where he regrouped behind a small ridge.[83] Merritt's retreat exposed Averell's left flank, and Breckinridge's men changed their focus to Averell. Breckinridge moved Captain George Beirne Chapman's Artillery into Fort Collier (misspelled on some maps as "Fort Collyer"), adjacent to the railroad line and Martinsburg Pike. Soon Averell retreated and regrouped further west of the pike. The Union cavalry pause enabled various Confederate forces to regroup, and Lee assumed command of the forces around Fort Collier. Breckinridge and Wharton moved adjacent to Gordon's Division.[83]

Wickham's Cavalry Brigade, commanded by Munford, had been moved from the north side of Red Bud Run to the Senseny Road to assist Lomax on Early's right. With Torbert's cavalry becoming even more of a threat, Early moved Munford to the west side of Winchester's heights. Munford discovered that Fort Jackson (a.k.a. Fort Milroy) was occupied by a small force.[97] Using a saber charge, Munford captured the fort and emplaced his two artillery pieces. From that high position, he could fire on Torbert's cavalry and Crook's infantry.[83]

Crook and Torbert continue forward

[edit]

Crook continued attacking Early's left. Gordon's Division and Patton's Brigade regrouped behind the right flank of the rest of Wharton's/Breckinridge's Division around 4:30 pm. The Confederate left flank was now behind a stone wall that ran perpendicular to the Martinsburg Pike and rail line. Braxton posted his artillery at intervals behind the wall. The Confederates had more artillery slightly north at Fort Collier, where Chapman's Battery had four guns, supported by Lee's force. More guns were located behind Gordon's Division, where Captain William M. Lowry's Wise Legion artillery was deployed.[92] This artillery stopped Crook's advance, but Lowry and two of Braxton's guns used up their ammunition and had to withdraw.[92]

Both Upton and Crook tried to persuade two regiments from the XIX Corps to attack the corner of the Confederate position, but the regiments refused because Emory ordered the XIX Corps to not go beyond the Second Woods. Upton then sent Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie and the 2nd Connecticut Heavy Artillery Regiment past the XIX Corps regiments to a rail fence where they fired upon Gordon's right flank.[99] They received unexpected assistance when Brigadier General James W. McMillan from Dwight's 1st Division of the XIX Corps arrived with the 160th New York Infantry Regiment, and deployed on Mackenzie's right flank. This caused Gordon's men to retreat, and Thoburn's men leapt the wall and attacked. Crook's entire army came forward, and they joined Upton's right—which also had the effect of sealing the XIX Corps out of the battle.[92] Battle's (Rodes') Division then withdrew toward Winchester in disorder, and Upton pushed the rest of his division forward from the left. His obstacle was the Baker House, which was on high ground containing Grimes's Brigade. Upton shifted Colonel Joseph Hamblin's Brigade up a ridge, and Grimes fell back to the L-shaped Smithfield Redoubt on high ground near the Smithfield House.[92]

Lee's force and Chapman's artillery held back Union cavalry on both sides of the pike. At the same time Upton attacked Breckinridge's right flank, Torbert's cavalry attacked his left at Fort Collier near the Martinsburg Pike. Torbert used a battery from the 3rd U.S. Artillery, commanded by Lieutenant William C. Cuyler, to kill 34 horses and mortally wound Captain Chapman.[92] Averell's Division turned the Confederate left flank against remnants of Bean's, Ferguson's, and Smith's cavalry brigades. Merritt sent Lowell's Reserve Brigade toward Fort Collier, and drove away Payne's Cavalry Brigade. Powell's Brigade flanked the fort from the west side of the pike, and Lowell captured the fort including two of Chapman's guns. Lee was seriously wounded in the leg during the engagement but escaped.[92]

The success of Upton's infantry and Torbert's cavalry inspired Crook's men to resume the attack, and the majority of Confederate troops were now running south through Winchester.[92] Confederate artillery saved Early's army from destruction.[92] At the Smithfield Redoubt, Nelson's battalion covered the approach of the Union infantry along Berryville Pike and Braxton's and McLaughlin battalions fired northward at Union cavalry. They also received some assistance from horse artillery on the Winchester Heights.[92]

Early's army makes final stand

[edit]

VI Corps presses from east

[edit]Early had Ramseur south of the Smithfield Redoubt near the Berryville Pike and Mt. Hebron Cemetery. Remnants of the divisions of Battle (Rodes), Gordon, and Breckinridge were in the redoubt. Various artillery units under the command of Colonel Thomas H. Carter were placed strategically throughout the area.[94] On the east side of the redoubt, Wright sent Getty and Ricketts to the right (north), but they were stymied by artillery.[note 11] Upton rode to the stalled 37th Massachusetts, took the regimental flag, and led the regiment forward. Soon the entire division was moving. Although Upton was wounded in the leg by a shell fragment and Edwards took over active command, Upton refused to leave the battlefield. The divisions of Ricketts and Getty were also moving forward. Getty passed the Baker mansion, but the VI Corps stalled again. Tompkins brought up the VI Corps batteries, and they were assisted from the north by du Pont's battery and Torbert's horse artillery. The Union crossfire eventually wounded Carter and killed all the artillery horses in the Smithfield Redoubt.[94]

Merritt and Crook advance from north

[edit]

Sheridan, now on the northern front, continued inspiring his men to attack. Merritt put together a force of less than 1,000 men to attack the northern side of the Confederate redoubt on the east side of the Martinsburg Pike. The force was led by Custer's Brigade with portions of the other two brigades, and attacked around 5:00 pm with Custer's band playing.[94][39] Observing the charge, Confederate brigade commander Forsberg was wounded twice, and successor Major William A. Yonce was mortally wounded minutes later. Breckinridge's men fired one volley, but could not reload before the Union cavalry was upon them with sabers.[94] This charge, combined with the earlier assault on Fort Collier and Devin's attack of Patton's Brigade, eliminated Breckinridge's Infantry Division. It had lost 1,200 men, nine battle flags, two brigade commanders, and dozens of officers.[94]

Despite Duval being shot in the thigh and relinquishing command to Hayes, Crook's infantry charged the Confederate redoubt and climbed over the north wall as the Confederates fled. Crook's army was joined by the VI Corps, led by Edwards and the 37th Massachusetts followed by the entire 1st Division, which ran up the hill and over the east wall of the redoubt. Ricketts' 3rd Division soon joined them.[94]

The Confederates fled in disorder south through Winchester. Ramseur brought his division south along the town's edge near the Front Royal Pike, and his men could see the Union Army entering the town. Crook's 36th Ohio Infantry Regiment led Hayes' 2nd Division through Winchester and cleared out small groups of Confederate skirmishers. Ramseur's men served as the rearguard on the Valley Pike as Early's army fled south.[94]

Wilson too late

[edit]With both of his brigade commanders wounded, Wilson's "performance deteriorated".[61] He tried to go around Lomax to gain the Valley Pike by looping south, but Lomax moved Johnson's Cavalry to the intersection of Front Royal Pike and Millwood Pike by 6:00 pm, and kept Wilson away.[94] Wilson missed his chance to intercept Early's retreating army, but he scattered Johnson's Cavalry Brigade and continued cross county toward Kernstown. He reached the Valley Pike around dusk, and halted his division about one mile (1.6 km) south of Winchester.[94] Two cavalry regiments from McIntosh's Brigade, the 3rd New Jersey and the 2nd Ohio, pursued enemy infantry until 10:00 pm when the division camped for the night.[46]

Fighting ends

[edit]

Darkness caused the end of the fighting.[61] The Confederate Army fled south up the Valley Pike, and many of the soldiers slept for a few hours in the fields between Kernstown and Newtown.[100] The Union Army camped in the fields around Winchester, and roll calls were conducted around 10:00 pm.[101] Many of the town's buildings became hospitals. Local families became hospital workers, and surgeons for both sides tended to the wounded. Sheridan sent a telegram to Grant, and ordered a 5:00 am march up the Valley Pike to chase Early's army.[101] The Confederate Army continued south before sunrise.[100] Early arrived at Fisher's Hill about dawn. The hill was known to southerners as their Gibraltar, and Early believed that its heights were impregnable.[102]

Casualties

[edit]The text of Early's casualty report made three weeks after the battle lists 3,611 killed, wounded, and missing—but excludes cavalry.[103] In a study that utilized regimental histories and correspondence in addition to official reports, one historian concluded that Early's Army of the Valley had 4,015 casualties.[104] Some sources list lower figures, but have the flaws with cavalry.[note 12] The Confederate infantry division with the highest killed and wounded was Rodes' Division, which had 686.[107] The high number reflects that division's counterattack at the gap between the two Union infantry corps and its fight with Russell's Division of Union infantry.[108] Deaths of Confederate infantry commanders included one division commander, Rodes, and two brigade commanders, Godwin and Patton. Another brigade commander, York, was seriously wounded and lost an arm. At the regimental level, 20 commanding officers were mortally wounded, wounded, or captured.[108] Lee, commander of Early's cavalry, was seriously wounded.[109]

Sheridan's Army of the Shenandoah lists 5,018 casualties in the official report; including 697 killed, 3,983 wounded, and 338 captured or missing.[110] The XIX Corps had 2,074 casualties, which includes 1,527 from Grover's 2nd Division. The high casualties for Grover reflect the Confederate counterattack by Gordon's Division.[108] Keifer's Second Brigade of Ricketts' Division had the most casualties in the VI Corps.[111] Among the army's leaders, the death of Russell and wounding of Upton were significant losses.[112]

Aftermath

[edit]Beginning at 5:00 am on September 20, Sheridan's army moved 20 miles (32 km) south to the north side of Strasburg in a march that took all day.[100] Two days later at Fisher's Hill, Crook flanked and turned Early's left in a sneak attack, and Early's army was again fleeing south.[113] Sheridan wrote that the Battle of Fisher's Hill "was, in a measure, a part of the battle of the Opequon; that is to say, it was an incident of the pursuit resulting from that action.[114]

Performance and impact

[edit]

One historian wrote that the Third Battle of Winchester was "the first one of the war in which cavalry, artillery and infantry were all used concurrently and to the best possible advantage, each according to its own nature and traditions."[89] Wilson agreed, writing that the battle was the first where "cavalry was properly handled in cooperation with the infantry".[115] At the time, the battle was "the bloodiest battle of the Shenandoah Valley", and caused "more casualties than the entire 1862 Valley Campaign".[116] Reflecting during and after the war, multiple soldiers on each side believed that this battle had the hardest fighting of the war.[112] Early's defeat was the first for a Confederate general in the Shenandoah Valley. Although he lost the battle, he handled his small army with "tactical skill and daring", making especially good use of his infantry and artillery.[117]

Sheridan made mistakes by funneling too many troops through the Berryville Canyon and holding Crook's army too far away while it was in reserve. Sheridan deserves credit for his perseverance and his ability to inspire his men, but the decisive maneuver—the attack on Early's left flank followed by the cavalry charge from the north—was implemented by Crook, not Sheridan.[118] Aside from his ability to inspire his troops, Sheridan's contribution was his handling and utilization of cavalry, which made the difference in the battle.[119] Merritt's cavalry division alone captured 775 men, seven battle flags, and two pieces of artillery.[120] Of the fifteen Medal of Honor winners in the battle, ten were members of the cavalry.[121] Early wrote that his Confederate army "deserved the victory, and would have had it, but for the enemy's immense superiority in cavalry, which alone gave it to him".[122]

Following his victory at Winchester, Sheridan received congratulations from Lincoln, Grant, and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton.[120] Some historians consider the battle to be the most important in the Shenandoah Valley.[105] Sheridan would have more success against Early, and Early's Army of the Valley was eliminated from the war on March 2, 1865, in the Battle of Waynesboro. Early escaped in that battle, but Custer's Division captured 1,700 men, 11 pieces of artillery, 17 battle flags, and Early's headquarters equipment.[123] Sheridan's success in the months following the Third Battle of Winchester propelled him to status only eclipsed by Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman, and he would eventually become Commanding General of the United States Army.[124] He was honored on U.S. Currency in the 1890s: ten-dollar treasury notes in 1890 and 1891, and five-dollar silver certificates in 1896.[125]

Preservation

[edit]

The Third Winchester Battlefield is part of the Shenandoah Valley Battlefields National Historic District. Major organizations involved with its preservation are the Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation, the American Battlefield Trust, and the Virginia Outdoors Foundation.[126] The battlefield is large, and includes the city plus land to the north and east. Much of the battlefield has been developed, and Interstate 81 and Virginia State Route 7 run through it. Portions of the battlefield east of Winchester are still farmland, and over 600 acres (240 ha) have been preserved.[127] A new Visitor Center is located one mile (1.6 km) east of Interstate 81 on Redbud Road.[128] The Winchester-Frederick County Convention and Visitors Bureau on Pleasant Valley Road also has information, including trail maps for the battlefield.[126]

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ During June 1864, Early had victories at the Battle of Lynchburg and Second Battle of Kernstown.[1][2] On July 9 in Maryland, he won the Battle of Monocacy in Maryland.[3] On July 11, Early threatened Washington in the Battle of Fort Stevens, but was repelled by reinforcements rushed to the battlefield. [4] In late July, Early sent Brigadier General John McCausland on a northern raid that resulted in the burning of the town of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania.[5]

- ^ At least one historian doubts that Sheridan planned for Crook to occupy the Valley Pike on the south side of Winchester, writing that Sheridan's orders on September 18 and actions on September 19 do not support that claim.[15]

- ^ Additions to Crook's command came from what had been the VIII Corps, causing it to be labeled as such for simplicity.[23] However, Army of West Virginia was the correct name, and both Sheridan and Crook used that name in their reports.[24]

- ^ Merritt identified the Opequon crossing used by the Reserve Brigade as Seivers' Ford.[49] However, one historian notes that since the crossing was immediately south of the Winchester and Potomac Railroad bridge, the crossing must have been Rocky Ford, which is about three fourths of a mile (1.21 km) north from Seiver's Ford.[43]

- ^ Leetown, West Virginia, (not Leetown, Virginia), is 16 miles (26 km) north of Winchester and five miles (8.0 km) east of Darkesville. The rocky terrain makes it advisable to travel on the turnpike.[50]

- ^ Historian Jeffry Wert differs from other sources on arrivals of reinforcements, writing that Rodes arrived before Gordon, and Gordon arrived before 10:00 am.[55] A colonel in Rodes' Division reported that when they arrived, they "found both Gordon's and Ramseur's divisions fighting."[56] Jubal Early wrote in 1912 that "Gordon's Division arrived first, a little after ten o'clock a.m."[57] Historian Scott Patchan indicates that Gordon reached the battlefield before Rodes.[47]

- ^ Although not mentioned by the corps commanders' reports, one source says the attack began at 11:40 am after a signal gun was discharged.[60]

- ^ The "First" and "Second" Woods did not have names, but have been called "First Woods" and "Second Woods" by historians. The same naming convention also applies to the "Middle Field". Examples of those three names being used can be found in reports by the National Park Service and American Battlefield Trust, and in books by Jeffry D. Wert and Scott Patchan.[64][65]

- ^ Sheridan wrote in 1888 that he ordered Crook to attack, while Crook wrote in 1864 that he was told by Sheridan to "place my command on the right and rear of the Nineteenth Corps, and to look out for our right...."[85] Crook later wrote that it was his responsibility for the decision to attempt to turn the enemy's left, and he sent an aide to inform Sheridan. Captain Henry A. du Pont, commanding Crook's artillery brigade with Crook that afternoon, agreed with Crook.[86]

- ^ The South Woods, with no official name and sometimes called the West Woods, was located south of the Second Woods and southwest of the First Woods.[91]

- ^ A movement by the VI corps left, instead of right, could have sealed Early's right flank and captured much of his army. One historian speculates that Wright may have been concerned with gaps in the line, especially after the trouble earlier in the day, and knew that Upton had already moved to the right to assist Crook.[94]

- ^ The National Park Service lists total Confederate casualties as 3,610 in a battle description, but as "nearly 4,000" in a narrative.[105] Another source says killed, wounded, and missing totaled to 3,600—but excluded cavalry which were "undoubtedly heavy".[106]

Citations

- ^ NPS Lynchburg Campaign.

- ^ NPS Kernstown II.

- ^ NPS Battle of Monocacy.

- ^ ABT Fort Stevens.

- ^ Gallagher (2006), p. xii.

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley (1902), p. 775; Pond (1883), p. 149.

- ^ a b ABT Lincoln Valley.

- ^ Pond (1883), p. 145.

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley (1902), p. 46.

- ^ a b Sheridan (1888), pp. 4–5.

- ^ Sheridan (1888), p. 6.

- ^ Sheridan (1888), p. 8.

- ^ Early & Early (1912), p. 419.

- ^ Sheridan (1888), pp. 9–10.

- ^ Wert (2010), p. 81.

- ^ a b c d Gallagher (2006), p. 14.

- ^ Wert (2010), p. 18.

- ^ Wert (2010), p. 21.

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley (1902), pp. 107–112.

- ^ Wert (2010), p. 20.

- ^ Wert (2010), p. 22.

- ^ Smithsonian Spencer Carbine.

- ^ Pond (1883), p. 121.

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley (1902), pp. 115, 360.

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley (1902), pp. 115.

- ^ Wert (2010), pp. 20–21.

- ^ HayesLibrary, A Friendship Forged in War.

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley (1902), p. 363.

- ^ The White House, William McKinley.

- ^ Gallagher (2006), p. ix; Patchan (2013), Appendix 1 of e-book.

- ^ Gallagher (2006), p. 16.

- ^ Patchan (2013), Appendix 3 of e-book.

- ^ NPS Opequon.

- ^ a b c Patchan (2013), Appendix 1 of e-book.

- ^ Senate, John Cabell Breckinridge.

- ^ ABT Stonewall Confederate Cemetery.

- ^ LOC Fitzhugh Lee.

- ^ ABT "Light Horse Harry" Lee.

- ^ a b LOC Battle Field of Winchester, VA (Opequon).

- ^ Croffut & Morris (1868), p. 718.

- ^ Pond (1883), p. 156.

- ^ Wert (2010), p. 47.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Patchan (2013), Ch.13 of e-book.

- ^ Wert (2010), p. 48.

- ^ Patchan (2013), Ch.13 of e-book; Rodenbough, Potter & Seal (1909), pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b c d Ainsworth & Kirkley (1902), p. 518.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Patchan (2013), Ch.14 of e-book.

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley (1902), pp. 443, 490.

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley (1902), p. 443.

- ^ Collins (2011), pp. 96–97.

- ^ Starr (1979), p. 241; Sutton (1892), p. 143.

- ^ NGA Charles Triplett O'Ferrall.

- ^ a b Pond (1883), pp. 157–158.

- ^ Patchan (2013), Ch.13 of e-book; Wert (2010), pp. 53–54.

- ^ Wert (2010), pp. 52–53.

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley (1902), p. 605.

- ^ Early & Early (1912), p. 421.

- ^ a b Ainsworth & Kirkley (1902), p. 427.

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley (1902), pp. 231, 279.

- ^ a b Wert (2010), p. 56.

- ^ a b c Wert (2010), p. 98.

- ^ Pond (1883), p. 158.

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley (1902), p. 318.

- ^ NPS Showdown in the Shenandoah.

- ^ Patchan (2013), Ch.14 of e-book; Wert (2010), p. 56.

- ^ Patchan (2013), Ch.15 of e-book.

- ^ Wert (2010), p. 57.

- ^ a b Ainsworth & Kirkley (1902), pp. 112–124.

- ^ Wert (2010), p. 62.

- ^ Wert (2010), p. 63.

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley (1902), p. 290.

- ^ a b c Patchan (2013), Ch. 16 of e-book.

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley (1902), p. 164.

- ^ Wert (2010), p. 70.

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley (1902), p. 47.

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley (1902), p. 150.

- ^ a b Wert (2010), p. 80.

- ^ a b c d Wert (2010), p. 77.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Patchan (2013), Ch. 17 of e-book.

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley (1902), p. 482.

- ^ Wert (2010), p. 78.

- ^ Wert (2010), pp. 78–79.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Patchan (2013), Ch. 18 of e-book.

- ^ Wert (2010), p. 83.

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley (1902), p. 361; Wert (2010), p. 82.

- ^ Wert (2010), p. 82.

- ^ a b c Wert (2010), p. 84.

- ^ Wert (2010), p. 79.

- ^ a b Sutton (1892), p. 160.

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley (1902), p. 368.

- ^ SVBNHD Save The West Woods.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Patchan (2013), Ch. 19 of e-book.

- ^ Tenney (1914), p. 131.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Patchan (2013), Ch. 20 of e-book.

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley (1902), p. 518; Patchan (2013), Ch. 20 of e-book.

- ^ Gallagher (2006), p. 361.

- ^ a b NPS Civil War Forts of Winchester.

- ^ MOHS James M. Schoonmaker.

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley (1902), p. 362; Patchan (2013), Ch. 19 of e-book.

- ^ a b c Wert (2010), p. 108.

- ^ a b Wert (2010), p. 99.

- ^ Wert (2010), pp. 109–110.

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley (1902), p. 555.

- ^ Patchan (2013), Appendix 5 of e-book.

- ^ a b NPS Third Battle of Winchester.

- ^ Kellogg (1903), pp. 204–205.

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley (1902), p. 557.

- ^ a b c Wert (2010), p. 103.

- ^ ABT Fitzhugh Lee.

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley (1902), p. 118.

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley (1902), pp. 112–119.

- ^ a b Wert (2010), p. 104.

- ^ Ainsworth & Kirkley (1902), p. 232.

- ^ Sheridan (1888), p. 24.

- ^ Starr (1979), pp. 277–278.

- ^ ABT Overview Third Winchester.

- ^ Wert (2010), pp. 106–107.

- ^ Wert (2010), pp. 104–105.

- ^ Starr (1979), pp. 276, 278.

- ^ a b Starr (1979), p. 277.

- ^ Patchan (2013), Appendix 6 of e-book.

- ^ Early & Early (1912), pp. 426–427.

- ^ Sutton (1892), p. 192.

- ^ Gallagher (2006), p. 28.

- ^ Blake (1908), pp. 13, 21.

- ^ a b Visit Winchester.

- ^ SVBNHD Winchester III Preservation.

- ^ ABT Winchester Battlefield.

Sources

- Ainsworth, Fred C.; Kirkley, Joseph W. (1902). The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies - Series I Volume XLIII Part I - Additions and Corrections, Chapter LV (pdf). Washington, District of Columbia: Government Printing Office. pp. 47–48, 107–112–124, 150, 164, 231–232, 279, 290, 318, 360–363, 368, 427, 443, 482, 490, 518, 555, 557605, 775. ISBN 978-0-91867-807-2. OCLC 427057. Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- Blake, George Herbert (1908). United States Paper Money; A Reference List of Paper Money, Including Fractional Currency, Issued Since 1861... (pdf). New York, New York: Wynkoop, Hallenbeck, Crawford Co. pp. 13, 21. OCLC 2070830.

- Collins, Joseph V. (2011). Battle Of West Frederick, July 7, 1864: Prelude To Battle of Monocacy. Bloomington, Indiana: Xlibris Corporation. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-1-46288-293-9. OCLC 1124479854. Retrieved 2020-11-06.

- Croffut, William Augustus; Morris, John M. (1868). The Military and Civil History of Connecticut During the War of 1861-65. New York, New York: Ledyard Bill. p. 718. LCCN 02012885. OCLC 1049684195. Retrieved 2020-11-16.

- Early, Jubal A.; Early, Ruth H. (1912). Lieutenant General Jubal Anderson Early, C.S.A. Autobiographical Sketch and Narrative of the War Between the States. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: J.B. Lippincott Co. pp. 419, 421, 426–427. LCCN 12026763. OCLC 262633752. Retrieved 2020-11-13.

- Gallagher, Gary W. (2006). The Shenandoah Valley Campaign of 1864. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. pp. ix, xii, 14, 16, 28, 361. ISBN 978-0-80783-005-5. OCLC 62281619.

- Kellogg, Sanford Cobb (1903). The Shenandoah Valley and Virginia, 1861 to 1865: A War Study. New York, New York: Neale Publishing Company. pp. 204–205. OCLC 612558785. Retrieved 2021-02-16.

- Patchan, Scott C. (2013). The Last Battle of Winchester: Phil Sheridan, Jubal Early, and the Shenandoah Valley Campaign, August 7-September 19, 1864. El Dorado Hills, Calif: Savas Beatie. p. 553. ISBN 978-1-932714-98-2. OCLC 857365201.

- Pond, George E. (1883). The Shenandoah Valley in 1864 (pdf). Campaigns of the Civil War. Vol. XI. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 121, 145, 149, 156–158. OCLC 13500039.

- Rodenbough, Theophilus F.; Potter, Henry C.; Seal, William P. (1909). History of the 18th Regiment of Cavalry Pennsylvania Volunteers (163 Regiment of the Line) 1862-1865 (pdf). New York, NY: Winkoop Hallenbeck Crawford Co. pp. 26–27. OCLC 6808979.

- Sheridan, Philip Henry (1888). Personal Memoirs of P. H. Sheridan, General, United States Army (pdf). Vol. II. New York, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 4–6, 8–10, 24. OCLC 703942811.

- Starr, Stephen Z. (1979). Union Cavalry in the Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. pp. 241, 277–279. ISBN 0-8071-0484-1. OCLC 4492585. Retrieved 2021-02-16.

- Sutton, Joseph J. (1892). History of the Second Regiment, West Virginia Cavalry Volunteers, During the War of the Rebellion (pdf). Portsmouth, OH: J. J. Sutton. pp. 141, 163, 192. LCCN 02015647. OCLC 1046521504.

- Tenney, Luman Harris (1914). War Diary of Luman Harris Tenney, 1861-1865 (pdf). Oberlin, Ohio: Frances Andrews Tenney. p. 131. OCLC 682089920.

- Wert, Jeffry D. (2010). From Winchester to Cedar Creek: The Shenandoah Campaign of 1864. Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press. pp. 18, 20–22, 47–48, 52–54, 56–57, 62–63, 70, 77–84, 98–99, 103–110, 112–119. ISBN 978-0-80932-972-4. OCLC 463454602.

- "Fitzhugh Lee". www.battlefields.org. American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- "Fort Stevens". www.battlefields.org. American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- "Henry "Light Horse Harry" Lee III". www.battlefields.org. American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- "Again into the Valley of Fire". www.battlefields.org. American Battlefield Trust. 17 September 2014. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- "Overview Third Winchester". www.battlefields.org. American Battlefield Trust. 8 January 2009. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- "WT Third Winchester Battlefield Trails Map". www.battlefields.org. American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- "Stonewall Confederate Cemetery". www.battlefields.org. American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- "Winchester Battlefield". www.battlefields.org. American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- "Fitzhugh Lee". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- Bvt. Lt. Col. G.L. Gillespie, Major of Engineers, U.S.A. (1873). "Battle Field of Winchester, VA (Opequon)". Washington, D.C.: The Honorable Secretary of War, and the Chief of Engineers, U.S.A. Retrieved 2020-09-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "James M. Schoonmaker". Congressional Medal of Honor Society. Retrieved 2021-03-07.

- "Charles Triplett O'Ferrall". National Governors Association. 13 January 2018. Retrieved 2021-02-21.

- "Battle of Monocacy, July 9, 1864". nps.gov. U.S. National Park Service. 2007. Retrieved 2020-11-10.

- "Civil War Forts of Winchester". nps.gov. U.S. National Park Service. 2007.

- "Battle Detail - Kernstown II". nps.gov. U.S. National Park Service. 2007. Retrieved 2020-11-10.

- "Lynchburg Campaign- June 14 - June 22, 1864". nps.gov. U.S. National Park Service. 2007. Retrieved 2020-11-10.

- "Battle Detail - Opequon". nps.gov. U.S. National Park Service. 2007. Retrieved 2020-11-05.

- "Showdown in the Shenandoah Valley: 1864 Valley Campaign". nps.gov. U.S. National Park Service. 2007.

- "Third Battle of Winchester". nps.gov. U.S. National Park Service. 2007.

- "George Crook and R.B.H.: A Friendship Forged in War". Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Library & Museums. Retrieved 2021-01-14.

- "United States Senate – John Cabell Breckinridge, 14th Vice President (1857–1861)". United States Senate. Retrieved 2020-11-14.

- "Spencer Carbine". Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Retrieved 2021-03-14.

- "Save 31 Acres at The West Woods". The Shenandoah Valley Battlefields National Historic District. Retrieved 2021-07-26.

- "Winchester III Preservation". The Shenandoah Valley Battlefields National Historic District. Archived from the original on 2021-07-26. Retrieved 2021-07-26.

- "Winchester Battlefield". Winchester-Frederick County Convention & Visitors Bureau. Retrieved 2021-07-26.

- "William McKinley". The White House. Retrieved 2020-12-07.

External links

[edit]- Frederick County, Virginia, in the American Civil War

- Valley campaigns of 1864

- Battles of the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War

- Union victories of the American Civil War

- Battles of the American Civil War in Virginia

- Winchester, Virginia

- Cavalry charges

- Conflicts in 1864

- 1864 in Virginia

- September 1864 events