User:R8R/sandbox

User:R8R/Rethinking rules on spellings of elements

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lead | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /lɛd/ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | metallic gray | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Pb) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lead in the periodic table | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 14 (carbon group) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | p-block | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Xe] 4f14 5d10 6s2 6p2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 32, 18, 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 600.61 K (327.46 °C, 621.43 °F) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 2022 K (1749 °C, 3180 °F) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 11.34 g/cm3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | common: +2, +4 −4,[3] −2,? −1,? 0,[4] +1,? +3? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.87 (+2) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 175 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 146±5 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | face-centered cubic (fcc) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 35.3 W/(m⋅K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 208 nΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | diamagnetic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | by Middle Easterns (7000 BCE) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Symbol | "Pb": from Latin plumbum | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isotopes of lead | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Isotopic abundances vary greatly by sample[6] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lead is a chemical element with atomic number 82 and symbol Pb (after the Latin plumbum). When freshly cut, it is bluish-white; it tarnishes to a dull gray upon exposure to air. It is a soft, malleable, and heavy metal with a density exceeding that of most common materials. Lead has the second-highest atomic number of the classically stable elements and lies at the end of three major decay chains of heavier elements.

Lead is a relatively unreactive post-transition metal. Its weak metallic character is illustrated by its amphoteric nature (lead and lead oxides react with both acids and bases) and tendency to form covalent bonds. Compounds of lead are usually found in the +2 oxidation state, rather than the +4 common with lighter members of the carbon group. Exceptions are mostly limited to organolead compounds. Like the lighter members of the group, lead exhibits a tendency to bond to itself; it can form chains, rings, and polyhedral structures.

Lead is easily extracted from its ores and was known to prehistoric people in Western Asia. A principal ore of lead, galena, often bears silver, and interest in silver helped initiate widespread lead extraction and use in ancient Rome. Lead production declined after the fall of Rome and did not reach comparable levels again until the Industrial Revolution. Nowadays, global production of lead is about ten million tonnes annually; secondary production from recycling accounts for more than half of that figure.

Lead has several properties that make it useful: high density, low melting point, ductility, and relative inertness to oxidation. Combined with relative abundance and low cost, these factors resulted in the extensive use of lead in construction, plumbing, batteries, bullets and shot, weights, solders, pewters, fusible alloys, and radiation shielding. In the late 19th century, lead was recognized as poisonous, and since then it has been phased out for many applications. Lead is a neurotoxin that accumulates in soft tissues and bones, damaging the nervous system and causing brain disorders and, in mammals, blood disorders.

Physical properties

[edit]Atomic

[edit]A lead atom has 82 electrons, arranged in an electron configuration of [Xe]4f145d106s26p2. The combined first and second ionization energies—the total energy required to remove the two 6p electrons—is close to that of tin, lead's upper neighbor in group 14. This is unusual since ionization energies generally fall going down a group as an element's outer electrons become more distant from the nucleus. The similarity is caused by the lanthanide contraction—the decrease in element radii from lanthanum (atomic number 57) to lutetium (71), and the relatively small radii of the elements after hafnium (72). The contraction is due to poor shielding of the nucleus by the lanthanide 4f electrons; the outer electrons are drawn towards the nucleus, resulting in smaller atomic radii. The combined first four ionization energies of lead exceed those of tin,[7] contrary to what periodic trends would predict. For this reason lead, unlike tin, mostly forms compounds in which it has an oxidation state of +2, rather than +4.[8] Relativistic effects, which become particularly prominent at the bottom of the periodic table, cause this behavior.[8][a] As a result, the 6s electrons of lead become reluctant to participate in bonding, a phenomenon called the inert pair effect. A related outcome is that the distance between nearest atoms in crystalline lead is unusually long.[10]

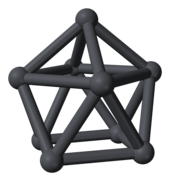

The lighter group 14 elements form stable or metastable allotropes having the tetrahedrally coordinated and covalently bonded diamond cubic structure. The energy levels of their outer s- and p-orbitals are close enough to allow mixing into four hybrid sp3 orbitals. In lead, the inert pair effect increases the separation between its s- and p-orbitals such that the gap cannot be overcome by the energy that would be released by hybridization.[11] Thus, rather than having a diamond-cubic structure, lead forms metallic bonds in which only the p-electrons are delocalized and shared between the Pb2+ ions. Lead consequently has a face-centered cubic structure like the similarly sized divalent metals calcium and strontium.[12] A quasicrystalline thin-film allotrope of lead, with pentagonal symmetry, was reported in 2013.[b]

Bulk

[edit]Freshly prepared lead has a bright silvery appearance with a hint of blue[15] but tarnishes on contact with moist air, resulting in a dull appearance with a hue that depends on the prevailing conditions. Characteristic properties of lead include high density, softness, malleability, ductility, poor electrical conductivity (compared to other metals), high resistance to corrosion (due to passivation), and a propensity to react with organic reagents.[15]

Lead's close packed face-centered cubic structure and high atomic weight result in a density[16] of 11.34 g/cm3, which is greater than that of common metals such as iron (7.87 g/cm3), copper (8.93 g/cm3), and zinc (7.14 g/cm3).[17] It is the origin of the idiom to go over like a lead balloon.[18] Some rarer metals are denser: tungsten and gold are both 19.3 g/cm3, and osmium— the densest metal known—has a density of 22.59 g/cm3, almost twice that of lead.[19]

Lead is a very soft metal with a Mohs hardness of 1.5; it can be scratched with a fingernail.[20] It is quite malleable and somewhat ductile.[c][21] The bulk modulus of lead—a measure of its ease of compressibility—is 45.8 GPa. In comparison, aluminium is 75.2 GPa; copper 137.8 GPa; and mild steel is 160–169 GPa.[22] Lead's tensile strength, at 12–17 MPa, is low (that of aluminium is 6 times higher, copper 10 times, and mild steel 15 times higher); it can be strengthened by adding small amounts of copper or antimony.[23]

The melting point of lead—at 327.5 °C (621.5 °F)[24]—is low compared to most metals.[25][d] Its boiling point of 1749 °C (3180 °F)[27] is the lowest among the group 14 elements. The electrical resistivity of lead at 20 °C is 208 nanoohm-meters, almost an order of magnitude higher than those of other industrial metals (copper at 17.12 nΩ·m; gold 22.55 nΩ·m; and aluminium at 27.09 nΩ·m). Lead is a superconductor at temperatures lower than 7.19 K;[28] this is the highest critical temperature of all type-I superconductors and the third highest of the elemental superconductors.[29]

Isotopes

[edit]

Isotopic abundances vary greatly by sample[6] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Pb) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Natural lead consists of four stable isotopes with mass numbers of 204, 206, 207, and 208,[31] and traces of five short-lived radioisotopes.[32] The high number of isotopes is due to lead's atomic number of 82 being even,[e] as well as a magic number (meaning lead's protons form complete shells within its atomic nucleus).[f] With its high atomic number, lead is the heaviest element whose natural isotopes are regarded as stable. This title was formerly held by bismuth, with an atomic number of 83, but its only primordial isotope was found in 2003 to decay at an extremely gradual rate.[g] The four stable isotopes of lead could theoretically undergo alpha decay to isotopes of mercury with a release of energy, but this has not been observed for any of them;[33] their predicted half-lives range from 1035 to 10189 years.[36]

Three of the stable isotopes are found in three of the four major decay chains: lead-206, lead-207, and lead-208 are the end decay products of uranium-238, uranium-235, and thorium-232, respectively; these decay chains are called the uranium series, actinium series, and thorium series. Their isotopic concentration in a natural rock sample depends on the presence of other elements. For example, the relative amount of lead-208 can range from 52.4% in normal samples to 90% in thorium ores.[37] (For this reason, the atomic weight of lead is given to only one decimal place.[38]) As time passes, the ratio of lead-206 and lead-207 to lead-204 increases, since the former two are supplemented by radioactive decay of heavier elements and the latter is not; this allows for lead–lead dating. As uranium decays into lead, their relative amounts change; this is the basis for uranium–lead dating.[39]

Apart from the stable isotopes, which make up almost all lead that exists naturally, there are trace quantities of a few radioactive isotopes. One of them is lead-210; although it has a half-life of 22.3 years,[33] some small quantities occur in nature because lead-210 is produced by a long decay series that starts with uranium-238 (which has been present for billions of years on Earth). Lead-214, -212, and -211 are present in the decay chains of uranium-238, thorium-232, and uranium-235, so traces of all three of these lead isotopes are found naturally. Minute traces of lead-209 result from the cluster decay of radium-223, one of the daughter products of natural uranium-235. Lead-210 is particularly useful for helping to identify the ages of samples by measuring lead-210 to lead-206 ratios (both isotopes are present in a single decay chain).[40][41]

In total, forty-three lead isotopes have been synthesized, with mass numbers 178–220.[33] Lead-205 is the most stable, with a half-life of around 1.5×107 years.[h] The second-most stable is the synthetic lead-202, which has a half-life of about 53,000 years, longer than any of the natural trace radioisotopes.[33]

Chemistry

[edit]

Bulk lead exposed to moist air forms a protective layer of varying composition. Lead carbonate is a common constituent;[43][44][45] the sulfate or chloride may also be present, in urban or maritime settings.[46] Finely divided powdered lead, as with many metals, is pyrophoric,[47] and burns with a bluish-white flame.[48]

The action of water on lead has the potential to make lead plumbing dangerous.[49] An excess of dissolved carbon dioxide in the carried water may result in the formation of soluble lead bicarbonate; oxygenated water may similarly dissolve lead as lead(II) hydroxide.[50] Drinking such water, over time, has the potential to cause health problems due to the toxicity of the dissolved lead.[i]

Fluorine reacts with lead at room temperature, forming lead(II) fluoride. The reaction with chlorine is similar but requires heating as the resulting chloride layer diminishes the reactivity of the elements.[46][52] Molten lead reacts with the chalcogens to give lead(II) chalcogenides.[53]

Lead metal is not attacked by dilute sulfuric acid but is dissolved by the concentrated form.[50] It reacts slowly with hydrochloric acid, and vigorously with nitric acid to form nitrogen oxides and lead(II) nitrate.[50] Organic acids, such as acetic acid, dissolve lead in the presence of oxygen.[46] Concentrated alkalis will dissolve lead and form plumbites.[49]

Inorganic compounds

[edit]Lead shows two main oxidation states: +4 and +2. The tetravalent state is common for group 14. The divalent state is rare for carbon and silicon, minor for germanium, important (but not prevailing) for tin, and is the more important for lead.[46] This is attributable to relativistic effects, specifically the inert pair effect, which manifests itself when there is a large difference in electronegativity between lead and, for example, oxide, halide, or nitride anions, leading to a significant partial positive charge on lead. The result is a stronger contraction of the lead 6s orbital than is the case for the 6p orbital, making it rather inert in ionic compounds. This is less applicable to compounds in which lead forms covalent bonds with elements of similar electronegativity such as carbon in organolead compounds. In them, the 6s and 6p orbitals remain similarly sized and sp3 hybridization is still energetically favorable. Lead, like carbon, is predominantly tetravalent in such compounds.[54]

There is a relatively large difference in the electronegativity of lead(II) at 1.87 and lead(IV) at 2.33. This difference marks the reversal in the trend of increasing stability of the +4 oxidation state going down group 14; tin, by comparison, has values of 1.80 in the +2 oxidation state and 1.96 in the +4 state.[55]

Lead(II)

[edit]Lead(II) compounds are characteristic of the inorganic chemistry of lead. Even strong oxidizing agents like fluorine and chlorine react with lead at room temperature to give only PbF2 and PbCl2.[56] Most are less ionic than the compounds of other metals and therefore largely insoluble. Lead(II) ions are usually colorless in solution,[57] and partially hydrolyze to form Pb(OH)+ and finally Pb4(OH)4 (in which the hydroxyl ions act as bridging ligands).[58] Unlike tin(II) ions, they are not reducing agents. Techniques for identifying the presence of the Pb2+ ion in water generally rely on the precipitation of lead(II) chloride via the addition of dilute hydrochloric acid. As the chloride is somewhat soluble in water, the precipitation of lead(II) sulfide, via the addition of hydrogen sulfide, is then attempted.[59]

Lead monoxide exists in two polymorphs, red α-PbO and yellow β-PbO, the latter being stable only above around 488 °C. It is the most commonly used compound of lead.[60] Its hydroxide counterpart, lead(II) hydroxide, is incapable of existence outside of solution; in solution, it is known to form plumbite anions.[61] Lead commonly reacts with heavier chalcogens. Lead sulfide is a semiconductor, a photoconductor, and an extremely sensitive infrared radiation detector. The other two chalcogenides, lead selenide and lead telluride, are likewise photo-conducting. They are unusual in that their color becomes lighter going down the group.[56]

Lead dihalides are well-characterized; this includes the diastatide,[62] and mixed examples, such as PbFCl. The relative insolubility of the latter forms a useful basis for the gravimetric determination of fluorine. The difluoride was the first ionically conducting compound to be discovered (in 1838, by Michael Faraday). The other dihalides decompose on exposure to ultraviolet or visible light, especially the diiodide.[63] Many pseudohalides are known.[56] Lead(II) forms an extensive variety of halide coordination complexes, such as [PbCl

4]2−

, [PbCl

6]4−

, and the [Pb

2Cl

9]5n−

n chain anion.[63]

Lead(II) sulfate is well known for its insolubility in water, like the sulfates of other heavy divalent cations. Lead(II) nitrate and lead(II) acetate are very soluble, and this is exploited in the synthesis of other lead compounds.[64]

Lead(IV)

[edit]Few inorganic lead(IV) compounds are known, and these are typically strong oxidants or exist only in highly acidic solutions.[8] Lead(II) oxide gives a mixed oxide on further oxidation, Pb

3O

4. It is described as lead(II,IV) oxide, or structurally 2PbO•PbO

2, and is the best-known mixed valence lead compound. Lead dioxide is a strong oxidizing agent, capable of oxidizing hydrochloric acid to chlorine gas. This is because the expected PbCl4 that would be produced is unstable and spontaneously decomposes to PbCl2 and Cl2. Analogously to lead monoxide, lead dioxide is capable of forming plumbate anions. Lead disulfide, like the monosulfide, is a semiconductor[65] as is lead(IV) selenide.[66] Lead tetrafluoride, a yellow crystalline powder, is stable, but less so than the difluoride. Lead tetrachloride (a yellow oil) decomposes at room temperature, lead tetrabromide is less stable still, and the existence of lead tetraiodide is questionable.[67][68]

Other oxidation states

[edit]

Some lead compounds exist in formal oxidation states other than +4 or +2. Lead(III) may be obtained, as an intermediate between lead(II) and lead(IV), in larger organolead complexes.[70][71] This oxidation state is not stable as the both the lead(III) ion and the larger complexes containing it are radicals; the same applies for lead(I), which can be found in such species.[72]

Numerous mixed lead(II,IV) oxides are known. When PbO2 is heated in air, it becomes Pb12O19 at 293 °C, Pb12O17 at 351 °C, Pb3O4 at 374 °C, and finally PbO at 605 °C. A further sesquioxide Pb2O3 can be obtained at high pressure, along with several non-stoichiometric phrases. Many of them show defect fluorite structures in which some oxygen atoms are replaced by vacancies: for instance, PbO can be considered as having such a structure, with every alternate layer of oxygen atoms absent.[73]

Negative oxidation states can occur as Zintl phases, as either free lead anions, for example, in Ba

2Pb, with lead formally being lead(−IV),[74] or in oxygen-sensitive cluster ions, for example, in a trigonal bipyramidal Pb2−

5 ion, where two lead atoms are lead(−I) and three are lead(0).[75] In such anions, each atom is at a polyhedral vertex and contributes two electrons to each covalent bond along an edge from their sp3 hybrid orbitals, the other two being an external lone pair.[58] They may be made in liquid ammonia via the reduction of lead by sodium.[76]

Organolead

[edit]

Carbon

Hydrogen

Lead

Lead can form multiply bonded chains, a property it shares with its lighter homolog, carbon. Its capacity to do so is much less because the Pb–Pb bond energy (98 kJ/mol) is far lower than that of the C–C bond (356 kJ/mol).[53] With itself lead can build metal–metal bonds of an order up to three.[77] With carbon, lead forms organolead compounds similar to, but generally less stable than, typical organic compounds[78] (due to the Pb–C bond being rather weak).[58] This makes the organometallic chemistry of lead far less wide-ranging than that of tin.[79] It predominantly forms organolead(IV) compounds. Very few organolead(II) compounds are known: even starting with inorganic lead(II) reactants results in organolead(IV) products. The most well-characterized exceptions are the purple bis(disyl)plumbylene, Pb[CH(SiMe)3)2]2 and lead cyclopentadienide, Pb(η5-C5H5)2.[79]

The simplest organic compound of lead is plumbane, an unstable analog of methane. Plumbane may be obtained in a reaction between metallic lead and atomic hydrogen.[80] Two simple derivatives, tetramethyllead and tetraethyllead, are the best-known organolead compounds. They may be made by the addition of trimethyllead or triethyllead to alkenes or alkynes; these precursors may themselves be made from the corresponding lead halides and lithium aluminium hydride at −78 °C. These compounds are relatively stable—tetraethyllead only starts to decompose at 100 °C (210 °F)[78]—or if exposed to sunlight or ultraviolet light.[81] (Tetraphenyllead is even more thermally stable, decomposing at 270 °C.)[79] With sodium metal, lead readily forms an equimolar alloy that reacts with alkyl halides to form organometallic compounds such as tetraethyllead.[82] The oxidizing nature of many organolead compounds is usefully exploited: lead tetraacetate is an important laboratory reagent for oxidation in organic chemistry;[83] tetraethyllead was once produced in larger quantities than any other organometallic compound.[84] Other organolead compounds are less chemically stable[78] or unknown.[80]

Origin and occurrence

[edit]In space

[edit]| Atomic number |

Element | Relative amount |

|---|---|---|

| 42 | Molybdenum | 0.798 |

| 46 | Palladium | 0.440 |

| 50 | Tin | 1.146 |

| 78 | Platinum | 0.417 |

| 80 | Mercury | 0.127 |

| 82 | Lead | 1 |

| 90 | Thorium | 0.011 |

| 92 | Uranium | 0.003 |

Lead 's per-particle abundance in the Solar System is 0.121 ppb (parts per billion).[85][j] This figure is two and a half times higher than that of platinum, eight times that of mercury, and seventeen times that of gold.[85] The amount of lead in the universe is slowly increasing[86] as most heavier atoms (all of which are unstable) gradually decay to lead. The abundance of lead in the Solar System since its formation some 4.5 billion years ago has increased by about 0.75%.[85] The solar system abundances table shows that lead, despite its relatively high atomic number, is more prevalent than most other elements with atomic numbers greater than 40.[85]

Primordial lead—which comprises the isotopes lead-204, lead-206, lead-207, and lead-208—was mostly created as a result of repetitive neutron capture processes occurring in stars. The two main modes of capture are the s- and r-processes.[87]

In the s-process (s is for "slow"), captures are separated by years or decades, allowing less stable nuclei to beta decay. For example, a stable thallium-203 nucleus captures a neutron and becomes thallium-204; this undergoes beta decay to give stable lead-204; on capturing another neutron, it becomes lead-205, which is stable enough to generally last longer than a capture takes (its half-life is around 15 million years). Further captures result in lead-206, lead-207, and lead-208. On capturing another neutron, lead-208 becomes lead-209, which quickly decays into bismuth-209. On capturing another neutron, bismuth-209 becomes bismuth-210, and this undergoes alpha decay to thallium-206 (which beta decays to lead-206), or beta decays to polonium-210 (which alpha decays to lead-206). The cycle ends at lead-206, lead-207, lead-208, and bismuth-209.[87]

In the r-process (r is for "rapid"), captures happen faster than nuclei can decay. This occurs in environments with a high neutron density, such as a supernova or the merger of two neutron stars. The neutron flux involved may be on the order of 1022 neutrons/(cm2·second).[88] The r-process does not form as much lead as the s-process. It tends to stop once neutron-rich nuclei reach 126 neutrons. At this point, the neutrons are arranged in complete shells within the atomic nucleus, and it becomes harder to energetically accommodate more of them. When the neutron flux subsides, these nuclei beta decay into stable isotopes of osmium, iridium, and platinum.[87]

On Earth

[edit]Lead is classified as a chalcophile under the Goldschmidt classification, meaning it is generally found combined with sulfur. It rarely occurs in its native, metallic form.[89] Many lead minerals are relatively light and, over the course of the Earth's history, have remained in the crust instead of sinking deeper into the Earth's interior. This accounts for lead's relatively high crustal abundance of 14 ppm; it is the 38th most abundant element in the crust.[90][k]

The main lead-bearing mineral is galena (PbS), which is mostly found with zinc ores.[89] Most other lead minerals are related to galena in some way; for example, boulangerite, Pb

5Sb

4S

11, is a mixed sulfide derived from galena; anglesite, PbSO

4, is a product of galena oxidation; and cerussite or white lead ore, PbCO

3, is a decomposition product of galena. Arsenic, tin, antimony, silver, gold, and bismuth are common impurities in lead minerals.[89]

World lead resources exceed 2 billion tons.[92] Significant deposits are located in Australia, China, Ireland, Mexico, Peru, Portugal, Russia, and the United States. Global reserves—resources that are economically feasible to extract—totaled 89 million tons in 2015, of which Australia had 35 million, China 15.8 million, and Russia 9.2 million.[92]

Typical background concentrations of lead do not exceed 0.1 μg/m3 in the atmosphere; 100 mg/kg in soil; and 5 μg/L in freshwater and seawater.[93]

Etymology

[edit]The modern English word "lead" is of Germanic origin; it comes from the Middle English leed and Old English lēad (with the macron above the "e" signifying that the vowel sound of that letter is long).[94] The Old English word is derived from the hypothetical reconstructed Proto-Germanic *lauda- ("lead").[95] According to accepted linguistic theory, this word bore descendants in most Germanic languages of exactly the same meaning.

The origin of the Proto-Germanic *lauda- is not agreed within the linguistic community. One hypothesis suggests it is derived from Proto-Indo-European *lAudh- ("lead"; capitalization of the vowel is equivalent to the macron).[96] Another hypothesis suggests it is borrowed from Proto-Celtic *ɸloud-io- ("lead"). This word is related to the Latin plumbum, which gave the element its chemical symbol Pb. The word *ɸloud-io- may also be the origin of Proto-Germanic *bliwa- (which also means "lead"), from which stemmed the German Blei.[97]

The name of the chemical element is not related to the verb of the same spelling, which is instead derived from (eventually) Proto-Germanic *laidijan- ("to lead").[98]

History

[edit]

(Years B.P. = years before 1950)[99]

Prehistory and early history

[edit]Metallic lead beads dating back to 7000–6500 BC have been found in Asia Minor and may represent the first example of metal smelting.[100] At this time lead had few (if any) applications due to its softness and dull appearance.[100] The major reason for the spread of lead production was its association with silver, which may be obtained by burning galena (a common lead mineral).[101][102] The Ancient Egyptians were the first to use lead in cosmetics, an application that spread to Ancient Greece and beyond;[103] the Egyptians may have used lead for sinkers in fishing nets, glazes, glasses, enamels, and for ornaments.[101] Various civilizations of the Fertile Crescent used lead as a writing material, as currency, and for construction.[101] Lead was used in the Ancient Chinese royal court as a stimulant,[101] as currency,[104] and as a contraceptive;[105] the Indus Valley civilization and the Mesoamericans[101] used it for making amulets; and the eastern and southern African peoples used lead in wire drawing.[106]

Classical era

[edit]Because silver was extensively used as a decorative material and an exchange medium, lead deposits came to be worked in Asia Minor from 3000 BC,[102] from 2000 BC in the Iberian peninsula by the Phoenicians; and in Athens, Carthage, and Sicily.[101]

This metal was by far the most used material in classical antiquity, and it is appropriate to refer to the (Roman) Lead Age. Lead was to the Romans what plastic is to us.

"Wine—An enological specimen bank", 1992[107]

Rome's territorial expansion in Europe and across the Mediterranean, and its development of mining, led to it becoming the greatest producer of lead during the classical era, with an estimated annual output peaking at 80,000 tonnes. Like their predecessors, the Romans obtained lead mostly as a by-product of silver smelting.[99][108][109] Lead mining occurred in Central Europe, Britain, the Balkans, Greece, Anatolia, and Hispania, with the latter accounting for 40% of world production.[99]

Lead was used for making water pipes in the Roman Empire; so much so that the Latin word for the metal, plumbum, is the origin of the English word "plumbing" and its derivatives. Its formability and resistance to corrosion[110] ensured its widespread use in other applications ranging from pharmaceuticals to roofing, and currency to warfare.[111][112][113] Writers of the time, such as the Cato the Elder, Columella, and Pliny the Elder, recommended lead (or lead-coated) vessels for the preparation of sweeteners and preservatives added to wine and food. The lead conferred an agreeable taste due to the formation of "sugar of lead" (lead(II) acetate) whereas copper or bronze vessels could impart a bitter flavor on account of verdigris formation.[114]

The Roman author Vitruvius reported the health dangers of lead[115] and modern writers have suggested that lead poisoning played a major role in the decline of the Roman Empire.[116][117][m] Other researchers have criticized such claims, citing errors in linking the fall of Rome to lead poisoning, and even "false evidence".[119][120] According to archaeological research, Roman lead pipes increased lead levels in tap water but such an effect was "unlikely to have been truly harmful".[121][122] When lead poisoning did occur, victims were called "saturnine" after the ghoulish father of the gods, Saturn, since they became dark and cynical. By association, lead was considered the father of all metals.[123] Its social status was low as it was readily available in Roman society[124] and cheap.[125]

Confusion with tin and antimony

[edit]During the classical era (and even up to the 17th century), tin was often not distinguished from lead: Romans called lead plumbum nigrum ("black lead"), and tin plumbum candidum ("bright lead"). The association of lead and tin can be seen in other languages: the word olovo in Czech translates to "lead", but in Russian the cognate олово (olovo) means "tin".[126] To add to the confusion, lead bore a close relation to antimony: both elements commonly occur as sulfides (galena and stibnite), often together. Pliny wrote that stibnite would give lead on heating, whereas the mineral produced on heating was antimony.[127] In countries such as Turkey and India, the originally Persian name surma came to refer to either antimony sulfide or lead sulfide,[128] and in some languages, such as Russian, gave its name to antimony (сурьма).[129]

Middle Ages and the Renaissance

[edit]

Lead mining in Western Europe declined after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, with Arabian Iberia being the only region having a significant output.[131][132] The largest production of lead occurred in South and East Asia, especially China and India, where lead mining grew strongly.[132]

In Europe, lead production only began to revive in the 11th and 12th centuries, where it was again used for roofing and piping; from the 13th century, lead was used to create stained glass.[132] In the European and Arabian traditions of alchemy, lead (symbol ![]() in the European tradition) was considered to an impure base metal which, by the separation, purification and balancing of its constituent essences, could be transformed to pure and incorruptible gold.[133] During the period, lead was used increasingly for adulterating wine. The use of such wine was forbidden in 1498 by a papal bull, as it was deemed unsuitable for use in sacred rites, but nevertheless continued to be imbibed and resulted in mass poisonings up to the late 18th century.[131][134] Lead was a key material in parts of the printing press, which was invented around 1440; lead dust was commonly inhaled by print workers, causing lead poisoning.[135] Firearms were invented at around the same time, and lead, despite being more expensive than iron, became the chief material for making bullets. It was less damaging to iron gun barrels, had a higher density (which allowed for better retention of velocity), and its lower melting point made the production of bullets easier as they could be made using a wood fire.[136] Archaeological work has revealed that lead cannonballs carried on the Mary Rose had jagged iron cores and this may represent an early example of armor piercing technology.[137] Lead, in the form of Venetian ceruse, was extensively used in cosmetics by Western European aristocracy as whitened faces were regarded as a sign of modesty.[103] This practice eventually expanded to white wigs and eyeliners, and only faded out with the French Revolution in the late 18th century. A similar fashion appeared in Japan in the 18th century with the emergence of the geishas, a practice that continued long into the 20th century. The white face became a "symbol of a Japanese woman", with lead commonly used as the whitener.[138][139][140]

in the European tradition) was considered to an impure base metal which, by the separation, purification and balancing of its constituent essences, could be transformed to pure and incorruptible gold.[133] During the period, lead was used increasingly for adulterating wine. The use of such wine was forbidden in 1498 by a papal bull, as it was deemed unsuitable for use in sacred rites, but nevertheless continued to be imbibed and resulted in mass poisonings up to the late 18th century.[131][134] Lead was a key material in parts of the printing press, which was invented around 1440; lead dust was commonly inhaled by print workers, causing lead poisoning.[135] Firearms were invented at around the same time, and lead, despite being more expensive than iron, became the chief material for making bullets. It was less damaging to iron gun barrels, had a higher density (which allowed for better retention of velocity), and its lower melting point made the production of bullets easier as they could be made using a wood fire.[136] Archaeological work has revealed that lead cannonballs carried on the Mary Rose had jagged iron cores and this may represent an early example of armor piercing technology.[137] Lead, in the form of Venetian ceruse, was extensively used in cosmetics by Western European aristocracy as whitened faces were regarded as a sign of modesty.[103] This practice eventually expanded to white wigs and eyeliners, and only faded out with the French Revolution in the late 18th century. A similar fashion appeared in Japan in the 18th century with the emergence of the geishas, a practice that continued long into the 20th century. The white face became a "symbol of a Japanese woman", with lead commonly used as the whitener.[138][139][140]

Outside Europe and Asia

[edit]In the New World, lead was produced soon after the arrival of European settlers. The earliest recorded lead production dates to 1621 in the English Colony of Virginia, fourteen years after its foundation.[141] In Australia, the first mine opened by colonists on the continent was a lead mine, in 1841.[142] Centuries before the Europeans were able to start colonizing Africa in the late 19th century, lead mining was known in the Benue Trough[143] and the lower Congo basin, where lead was used for trade with the predecessors of the same Europeans, and as a currency.[144][n]

Industrial Revolution

[edit]

In the second half of the 18th century Britain, and later continental Europe and the United States, experienced the Industrial Revolution. During the period, lead mining proved important; the Industrial Revolution was the first time during which production rates exceeded those of Rome.[99] Britain was the leading producer, losing this status by the mid-19th century with the depletion of its mines and the development of lead mining in Germany, Spain, and the United States.[145] By 1900, the United States dominated global lead production,[146] and other non-European nations—Canada, Mexico, and Australia—had begun significant production.[147] A great share of the demand for lead came from plumbing and painting—lead paints were in regular use.[148] At this time, more (working class) people contacted the metal and lead poisoning cases escalated. This led to research into the effects of lead intake. Lead was proven to be more dangerous in its fume form than as a solid metal. Lead poisoning and gout were linked; British physician Alfred Baring Garrod noted a third of his gout patients were plumbers and painters. The effects of chronic ingestion of lead, including mental disorders, were also studied in the 19th century. The first laws aimed at decreasing lead poisoning in factories were enacted during the 1870s and 1880s in the United Kingdom.[148]

Modern era

[edit]

Further evidence of the threat that lead posed to humans was discovered in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Mechanisms of harm were better understood, and lead blindness was documented. Countries in Europe and the United States started efforts to reduce the amount of lead that people came into contact with. The United Kingdom first introduced mandatory factory inspections in 1878 and appointed the first Medical Inspector of Factories in 1898; as a result, a 25-fold decrease in lead poisoning incidents from 1900 to 1944 was reported.[149] The last major human exposure to lead was the addition of tetraethyllead to gasoline as an antiknock agent, a practice that originated in the United States in 1921. It was phased out in the United States and the European Union by 2000.[148] Most European countries banned lead paint—commonly used to this point because of its opacity and water resistance[150]—for interiors by 1930.[151] The impact was significant: in the last quarter of the 20th century, the percentage of people with excessive lead blood levels dropped from over three-quarters of the United States population to slightly over two percent.[148] The main product made of lead by the end of the 20th century was the lead–acid battery,[152] which posed no direct threat to humans. From 1960 to 1990, lead output in the Western Bloc grew by a third.[153] The share of the world's lead production by the Eastern Bloc tripled, from 10% to 30%, from 1950 to 1990, with the Soviet Union being the world's largest producer during the mid-1970s and the 1980s, and China starting major lead production in the late 20th century.[154] Unlike the European communist countries, China was largely unindustrialized by the mid-20th century; in 2004, China surpassed Australia as the largest producer of lead.[155] As with European industrialization, lead has had a negative effect on health in China.[156]

Production

[edit]

Production and consumption of lead is increasing worldwide due to its use in lead–acid batteries.[157] There are two major categories of production: primary, from mined ores; and secondary from scrap. In 2013, 4.74 million metric tons came from primary production and 5.74 million from secondary production. The top three producers of mined lead concentrate in that year were China, Australia, and the United States. The top three producers of refined lead were China, the United States, and Germany.[158] According to the International Resource Panel's Metal Stocks in Society report of 2010, the total amount of lead in use, stockpiled, discarded or dissipated into the environment, on a global per capita basis, is 8 kg. Much of this is in more developed countries (20–150 kg per capita) rather than less developed ones (1–4 kg per capita).[159]

Production processes for primary and secondary lead are similar. Some primary production plants now supplement their operations with scrap lead, and this trend is likely to increase in the future. Given adequate techniques, secondary lead is indistinguishable from primary lead. Scrap lead from the building trade is usually fairly clean and is re-melted without the need for smelting, though refining is sometimes needed. Secondary lead production is therefore cheaper, in terms of energy requirements, than is primary production, often by 50% or more.[160]

Primary

[edit]Most lead ores contain a low percentage of lead—lead-rich ores have a typical content of 3–8%—which must be concentrated for extraction.[161] During initial processing, ores typically undergo crushing, dense-medium separation, grinding, froth flotation, and drying. The resulting concentrate, which has a lead content of 30–80% by mass (regularly 50–60%),[161] is then turned into (impure) lead metal.

There are two main ways of doing this: a two-stage process involving roasting followed by blast furnace extraction, carried out in separate vessels; or a direct process in which the extraction of the concentrate occurs in a single vessel. The latter has become the most common route, though the former is still significant.[162]

Two-stage process

[edit]First, the sulfide concentrate is roasted in air to oxidize the lead sulfide:[163]

- 2 PbS + 3 O2 → 2 PbO + 2 SO2↑

| Country | Output (thousand tons) |

|---|---|

| 2,300 | |

| 633 | |

| 385 | |

| 300 | |

| 240 | |

| 130 | |

| 90 | |

| 82 | |

| 76 | |

| 54 | |

| 45 | |

| 40 | |

| 40 | |

| 38 | |

| 33 | |

| Other countries | 226 |

As the original concentrate was not pure lead sulfide, roasting yields lead oxide and a mixture of sulfates and silicates of lead and other metals contained in the ore.[164] This impure lead oxide is reduced in a coke-fired blast furnace to the (again, impure) metal:[165][166]

- 2 PbO + C → Pb + CO2↑

Impurities are mostly arsenic, antimony, bismuth, zinc, copper, silver, and gold. The melt is treated in a reverberatory furnace with air, steam, and sulfur, which oxidizes the impurities except for silver, gold, and bismuth. Oxidized contaminants float to the top of the melt and are skimmed off.[167][168] Metallic silver and gold are removed and recovered economically by means of the Parkes process, in which zinc is added to lead. The zinc adsorbs silver and gold, both of which, being immiscible in lead, can be separated and retrieved.[169][168] De-silvered lead is freed of bismuth by the Betterton–Kroll process, treating it with metallic calcium and magnesium. The resulting bismuth dross can be skimmed off.[168]

Very pure lead can be obtained by processing smelted lead electrolytically using the Betts process. Anodes of impure lead and cathodes of pure lead are placed in an electrolyte of lead fluorosilicate (PbSiF6). Once electrical potential is applied, impure lead at the anode dissolves and plates out on the cathode leaving the impurities in solution.[168][170] This technique is costly and is only currently used for refining lead.[171]

Direct process

[edit]In this process lead bullion and slag is obtained directly from lead concentrates. The lead sulfide concentrate is charged directly to a furnace, melted, and oxidized, forming lead monoxide. Carbon (coke or gas) is added to the molten charge along with fluxing agents. The lead monoxide is thereby reduced to metallic lead, in the midst of a slag rich in lead monoxide.

As much as 80% of the lead in very high-content initial concentrates can be obtained as bullion; the remaining 20% resides in a slag rich in lead monoxide. For a low-grade feed, all of the lead can be oxidized to a high-lead slag.[162] Metallic lead is further obtained from the high-lead (25–40%) slags via submerged fuel combustion or injection, reduction assisted by an electric furnace, or a combination of both.[162]

Alternatives

[edit]Research on a cleaner, less energy-intensive, lead extraction process continues; a major drawback is that the alternatives result in either a high sulfur content in the resulting lead metal, or too much lead is lost as waste. Hydrometallurgical extraction, in which anodes of impure lead are immersed into an electrolyte and pure lead is deposited onto a cathode, is technique that may have potential.[171]

Secondary

[edit]Smelting, which is an essential part of the primary production, is often skipped during secondary production. It is only performed when metallic lead had undergone significant oxidation.[160] The process is similar to that of primary production in either a blast furnace or a rotary furnace, with the essential difference being the greater variability of yields. The Isasmelt process is a more recent method that may act as an extension to primary production; the essence of this process is that battery paste from spent lead–acid batteries is deprived of its sulfur content (by, for example, treating it with alkalis) and then treated in a coal-fueled furnace in the presence of oxygen, which eventually yields impure lead, with antimony being the most common impurity.[172] Refining of secondary lead is similar to that of primary lead; some refining processes may be skipped depending on the material recycled and its potential contamination, with bismuth and silver most commonly being accepted as impurities.[172]

Of the sources of lead for recycling, lead–acid batteries are the most important; lead pipe, sheet, and cable sheathing are also significant.[160]

Applications

[edit]

Contrary to popular belief, pencil leads in wooden pencils have never been made from lead. When the pencil originated as a wrapped graphite writing tool, the particular type of graphite used was named plumbago (literally, act for lead or lead mockup).[174]

Elemental form

[edit]Lead metal has several useful mechanical properties, including high density, low melting point, ductility, and relative inertness. Many metals are superior to lead in some of these aspects but lead is more common than most of these metals, and lead-bearing minerals are easier to mine and process than those of many other metals. One disadvantage of using lead is its toxicity, which explains why it has been phased out for some uses.[175]

Lead has been used for bullets since their invention in the Middle Ages. It is inexpensive; its low melting point means small arms ammunition and shotgun pellets can be cast with minimal technical equipment; and it is denser than other common metals (which allows for better retention of velocity). In cast bullets, lead is sometimes alloyed with tin or antimony: this increases the cost and time of making the bullet, but increases its hardness (thereby making the bullet more effective against hard targets), reduces tension on the gun barrel and does not contaminate it with lead, as simple lead bullets do.[176]. Concerns have been raised that lead bullets used for hunting can damage the environment.[o]

Its high density and resistance to corrosion have been exploited in a number of related applications. It used as ballast in sailboat keels.[178] Its weight allows it to counterbalance the heeling effect of wind on the sails; being so dense it takes up a small volume, thus minimizing underwater resistance. It is used in scuba diving weight belts to counteract the diver's buoyancy.[179] In 1993, some 600 tonnes of lead were used to stabilize the base of the Leaning Tower of Pisa.[180] Because of its corrosion resistance, lead is used as a protective sheath for (seabed) submarine cables.[181]

The high density and atomic number of lead, combined with its relatively low cost, malleability and low melting point, helped establish lead as a radiation shielding material. A gamma ray, for example, can be absorbed by an electron, potentially knocking it out from its atom. The high density of lead means that lead atoms are densely packed and the electron density is high; the high atomic number means there are many electrons per atom.[182] In its molten form, it has been used as a coolant for lead-cooled fast reactors.[183]

Lead is added to copper alloys such as brass and bronze, to improve machinability and for its lubricating qualities. Being practically insoluble in copper the lead forms solid globules permeated throughout imperfections within the alloy, such as grain boundaries. In low concentrations, as well as acting as lubricants, these globules hinder the formation of large chips as the alloy is worked, thereby improving machinability. Copper alloys with larger concentrations of lead are used in bearings. The lead provides lubrication; the copper provides the load bearing support.[184]

Sheet-lead is used as a sound deadening layer in the walls, floors and ceilings of sound studios.[185][186] It is the traditional base metal of organ pipes, mixed with various amounts of tin to control the tone of each pipe.[187][188]

Lead has many uses in the construction industry; for example, lead sheets are used as architectural metals in roofing material, cladding, flashing, gutters and gutter joints, and on roof parapets.[189][190] Detailed lead moldings are used as decorative motifs to fix lead sheet. Lead is still used in statues and sculptures,[p] including for armatures.[192] In the past it was often used to balance the wheels of a car; for environmental reasons this use is being phased out in favor of other materials.[193]

The largest use of lead in the early 21st century is in lead–acid batteries. The reactions in the battery between lead, lead dioxide, and sulfuric acid provide a reliable source of voltage.[q] The lead in batteries undergoes no direct contact with humans, so there are fewer toxicity concerns. Supercapacitors incorporating lead-acid batteries have been installed in kilowatt and megawatt scale applications in Australia, Japan, and the United States in frequency regulation, solar smoothing and shifting, wind smoothing, and other applications.[195][196]

Lead is used in electrodes for electrolysis, and in high voltage power cables as sheathing material to prevent water diffusion into insulation. Its use in solder for electronics is being phased out by some countries to reduce the amount of environmentally hazardous waste. Lead is one of three metals used in the Oddy test for museum materials, helping detect organic acids, aldehydes, and acidic gases.

Compounds

[edit]Lead compounds are used as, or in, coloring agents, oxidants, plastic, candles, glass, and semiconductors. Lead-based coloring agents are used in ceramic glazes and glass, notably for red and yellow shades.[197][198] Lead tetraacetate and lead dioxide are used as oxidizing agents in organic chemistry. Lead is frequently used in the polyvinyl chloride plastic coating of electrical cords.[199][200] Lead is used to treat some candle wicks to ensure a longer, more even burn. Because of its toxicity, European and North American manufacturers use alternatives such as zinc.[201][202] Lead glass is composed of 12–28% lead oxide. It changes the optical characteristics of the glass and reduces the transmission of ionizing radiation.[203] Lead-based semiconductors, such as lead telluride, lead selenide, and lead antimonide are used in photovoltaic cells and infrared detectors.[204]

Biological and environmental effects

[edit]Biological

[edit]

Lead has no confirmed biological role.[205] Its prevalence in the human body—at an adult average of 120 mg[r]—is nevertheless exceeded only by zinc (2500 mg) and iron (4000 mg) of all metals.[207] Lead salts are very quickly and efficiently absorbed by the body.[208] A small amount of lead (1%) will be stored in bones; the rest will be excreted in urine and feces within a few weeks of exposure. Only about a third of lead will be excreted by a child. Continuous exposure may result in the bioaccumulation of lead.[209]

Toxicity

[edit]Lead is a highly poisonous metal (whether inhaled or swallowed), affecting almost every organ and system in the human body.[210] At airborne levels of 100 mg/m3, it is immediately dangerous to life and health.[211] Lead is rapidly absorbed into the bloodstream.[212] The primary cause of its toxicity is its predilection for interfering with the proper functioning of enzymes. It does so by binding to the sulfhydryl groups found on many enzymes,[213] or mimicking and displacing other metals which act as cofactors in many enzymatic reactions.[214] Among the essential metals that lead interacts with are calcium, iron, and zinc.[215] High levels of calcium and iron tend to provide some protection from lead poisoning; low levels cause increased susceptibility.[208]

Effects

[edit]Lead can cause severe damage to the brain and kidneys in adults or children and, ultimately, death. By mimicking calcium, lead can cross the blood-brain barrier. It degrades the myelin sheaths of neurons, reduces their numbers, interferes with neurotransmission routes, and decreases neuronal growth.[213]

Symptoms of lead poisoning include nephropathy, colic-like abdominal pains, and possibly weakness in the fingers, wrists, or ankles. Small blood pressure increases, particularly in middle-aged and older people, may be apparent and can cause anemia. In pregnant women, high levels of exposure to lead may cause miscarriage. Chronic, high-level exposure has been shown to reduce fertility in males.[216] In a child's developing brain, lead interferes with synapse formation in the cerebral cortex, neurochemical development (including that of neurotransmitters), and the organization of ion channels.[217] Early childhood exposure has been linked with an increased risk of sleep disturbances and excessive daytime sleepiness in later childhood.[218] High blood levels are associated with delayed puberty in girls.[219] Exposure to airborne lead from the combustion of tetraethyl lead in gasoline, most notably in the 20th century, has been linked with historical increases in crime levels (a hypothesis which is not universally accepted).[220]

Despite the toxicity of lead in significant amounts, there is some evidence that trace amounts are beneficial in pigs and rats, and that its absence causes deficiencies such as depressed growth, anemia, and disturbed iron metabolism. If this finding holds for humans it would make lead an essential element, one with a threshold of toxicity so low that lead toxicity would remain a much higher priority than lead deficiency.[221][222][223][224]

Treatment

[edit]Treatment for lead poisoning normally involves the administration of dimercaprol and succimer.[225] Acute cases may require the use of disodium calcium edetate, this being the calcium chelate of the disodium salt of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA). It has a greater affinity for lead than calcium with the result that lead chelate is formed by exchange and excreted in the urine, leaving behind harmless calcium.[226]

Exposure sources

[edit]

Lead exposure is a global issue as lead mining and lead smelting are common in many countries. Poisoning typically results from ingestion of food or water contaminated with lead, and less commonly after accidental ingestion of contaminated soil, dust, or lead-based paint.[227] Fruit and vegetables can be contaminated by high levels of lead in the soils they were grown in. Soil can be contaminated through particulate accumulation from lead in pipes, lead paint, and residual emissions from leaded gasoline.[228] The use of lead for water pipes is problematic in areas with soft or acidic water. Hard water forms insoluble layers in the pipes whereas soft and acidic water dissolves the lead pipes.[229]

Ingestion of lead-based paint is the major source of exposure for children. As the paint deteriorates, it peels, is pulverized into dust and then enters the body through hand-to-mouth contact or contaminated food, water, or alcohol. Ingesting certain home remedies may result in exposure to lead or its compounds.[230] Inhalation is the second major exposure pathway, including for smokers, and especially for workers in lead-related occupations.[231] Cigarette smoke contains, among other toxic substances, radioactive lead-210.[232] Almost all inhaled lead is absorbed into the body; for ingestion, the rate is 20–70%, with children absorbing lead at a higher rate than adults.[233]

Dermal exposure may be significant for a narrow category of people working with organic lead compounds. The rate of skin absorption is lower for inorganic lead.[234]

Environmental

[edit]The extraction, production, use, and disposal of lead and its products have caused significant contamination of the Earth's soils and waters. Atmospheric emissions of lead were at their peak during the Industrial Revolution and the leaded gas period in the second half of the twentieth century. Elevated concentrations of lead persist in soils and sediments in post-industrial and urban areas, and industrial emissions, including those arising from coal burning,[235] continue in many parts of the world.[236]

Lead can accumulate in soils, especially those with a high organic content, where it remains for hundreds to thousands of years. It can take the place of other metals within plants and can accumulate on their surfaces, thereby retarding photosynthesis, and preventing their growth or killing them. Contamination of soils and plants then affects microorganisms and animals. Affected animals have a reduced ability to synthesize red blood cells.

Restriction and remediation

[edit]By the mid-1980s, a significant shift in lead use had taken place. In the United States, environmental regulations reduced or eliminated the use of lead in non-battery products, including gasoline, paints, solders, and water systems. Particulate control devices can be used in coal-fired power plants to capture lead emissions.[235] Lead use is being further curtailed by the European Union's Restriction of Hazardous Substances Directive.[237] The use of lead shot for hunting and sport shooting was banned by the Netherlands in 1993, resulting in a large drop in lead emissions, from 230 tonnes in 1990 to 47.5 tonnes in 1995.[238]

In the United States, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration has set the permissible exposure limit for lead exposure in the workplace as 0.05 mg/m3 over an 8-hour workday; this applies to metallic lead, inorganic lead compounds, and lead soaps. The US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health has set a recommended exposure limit of 0.05 mg/m3 over an 8-hour workday and recommends that workers' blood concentrations of lead stay below 0.06 mg per 100 g of blood.

Lead may still be found in harmful quantities in stoneware,[239] vinyl[240] (such as that used for tubing and the insulation of electrical cords), and Chinese brass.[s] Old houses may still contain lead paint.[240] White lead paint has been withdrawn from sale in industrialized countries, but yellow lead chromate remains in use. Stripping old paint by sanding produces dust which can be inhaled.[242] Lead abatement programs have been mandated by some authorities, for example in properties where young children live.[243]

Lead waste, depending of the jurisdiction and the nature of the waste, may be treated as household waste (in order to facilitate lead abatement activities),[244] or potentially hazardous waste requiring specialized treatment or storage.[245] Research has been conducted on how to remove lead from biosystems by biological means. Fish bones are being researched for their ability to bioremediate lead in contaminated soil.[246][247] The fungus Aspergillus versicolor is effective at removing lead ions.[248] Several bacteria have been researched for their ability to reduce lead, including the sulfate-reducing bacteria Desulfovibrio and Desulfotomaculum, both of which are highly effective in aqueous solutions.[249]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ About 10% of the lanthanide contraction has been attributed to relativistic effects.[9]

- ^ The allotrope was obtained by depositing lead atoms on the surface of an icosahedral silver-indium-ytterbium quasicrystal. Its electronic nature—whether it was metallic or an insulator (or something in between)—was not recorded.[13][14]

- ^ Malleability describes how easily it deforms under compression, whereas ductility means its ability to stretch.

- ^ A (wet) finger can be dipped into molten lead without risk of a burning injury.[26]

- ^ An even number of either protons or neutrons generally increases the nuclear stability of isotopes, compared to isotopes with odd numbers. No elements with odd atomic number has more than two stable isotopes; even-numbered elements have multiple stable isotopes, with tin (element 50) having the highest number of isotopes of all elements, ten.[33] See Even and odd atomic nuclei for more details.

- ^ Lead 208 is doubly magic, and especially stable against decay, as its 126 neutrons also form a complete shell.

- ^ The half-life found in the experiment was 1.9×1019 years.[34] A kilogram of natural bismuth would have an activity value of approximately 0.003 becquerels (decays per second). For comparison, the activity value of natural radiation within the human body is around 65 becquerels per kilogram of body weight (4500 becquerels on average).[35]

- ^ It decays solely via electron capture, which means when there are no electrons available and lead is fully ionized with all 82 electrons removed it cannot decay. Fully ionized thallium-205, the isotope lead-205 would decay to, becomes unstable and can decay into a bound state of lead-205.[42]

- ^ The harder the water the more calcium bicarbonate and sulfate it will contain, and the more the inside of the pipes will be coated with a protective layer of lead carbonate or lead sulfate.[51]

- ^ Abundances in the source are listed relative to silicon rather than in per-particle notation. The sum of all elements per 106 parts of silicon is 2.6682×1010 parts; lead comprises 3.258 parts.

- ^ Elemental abundance figures are estimates and their details may vary from source to source.[91]

- ^ The inscription reads: "Made when the Emperor Vespasian was consul for the ninth term and the Emperor Titus was consul for the seventh term, when Gnaeus Iulius Agricola was imperial governor (of Britain)."

- ^ The fact that Julius Caesar fathered only one child, as well as the alleged sterility of his successor, Caesar Augustus, have been attributed to lead poisoning.[118]

- ^ It is not known when mining was first performed in the region because no written records were kept, but there are 17th-century European records of trade with the Congolese, which indicate lead was being smelted by then.[144]

- ^ For instance, California banned lead bullets for hunting on that basis in April 2015.[177]

- ^ For example, a firm "...producing quality [lead] garden ornament from our studio in West London for over a century".[191]

- ^ See[194] for details on how a lead–acid battery works.

- ^ Rates vary greatly by country.[206]

- ^ An alloy of brass (copper and zinc) with lead, iron, tin, and sometimes antimony.[241]

References

[edit]- ^ "Standard Atomic Weights: Lead". CIAAW. 2020.

- ^ a b Prohaska, Thomas; Irrgeher, Johanna; Benefield, Jacqueline; Böhlke, John K.; Chesson, Lesley A.; Coplen, Tyler B.; Ding, Tiping; Dunn, Philip J. H.; Gröning, Manfred; Holden, Norman E.; Meijer, Harro A. J. (2022-05-04). "Standard atomic weights of the elements 2021 (IUPAC Technical Report)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. doi:10.1515/pac-2019-0603. ISSN 1365-3075.

- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ Pb(0) carbonyls have been observered in reaction between lead atoms and carbon monoxide; see Ling, Jiang; Qiang, Xu (2005). "Observation of the lead carbonyls PbnCO (n=1–4): Reactions of lead atoms and small clusters with carbon monoxide in solid argon". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 122 (3): 034505. 122 (3): 34505. Bibcode:2005JChPh.122c4505J. doi:10.1063/1.1834915. ISSN 0021-9606. PMID 15740207.

- ^ a b Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S.; Audi, G. (2021). "The NUBASE2020 evaluation of nuclear properties" (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 45 (3): 030001. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/abddae.

- ^ a b c Meija et al. 2016.

- ^ Lide 2004, p. 10-179.

- ^ a b c Polyanskiy 1986, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Pyykko 1988, pp. 563–94.

- ^ Norman 1996, p. 36.

- ^ Greenwood & Earnshaw 1998, pp. 374, 226–27.

- ^ Christensen 2002, pp. 867–68.

- ^ Sharma et al. 2013.

- ^ Sharma et al. 2014, p. 174710.

- ^ a b Polyanskiy 1986, p. 18.

- ^ Thornton, Rautiu & Brush 2001, p. 6.

- ^ Lide 2004, pp. 12-35–12-37.

- ^ Jones 2014, p. 42.

- ^ Lide 2004, pp. 4-39–4-96.

- ^ Vogel & Achilles 2013, p. 8.

- ^ Anderson 1869, pp. 341–43.

- ^ Gale & Totemeier 2003, pp. 15–2–15–3.

- ^ Thornton, Rautiu & Brush 2001, p. 8.

- ^ Lide 2004, p. 12-220.

- ^ Koshal 2014, p. 1/92.

- ^ Willey 1999.

- ^ Lide 2004, p. 12-219.

- ^ Blakemore 1985, p. 272.

- ^ Webb, Marsiglio & Hirsch 2015.

- ^ "Standard Atomic Weights: Lead". CIAAW. 2020.

- ^ Polyanskiy 1986, p. 16.

- ^ University of California Berkeley Nuclear Forensic Search Project.

- ^ a b c d e Livechart.

- ^ Marcillac et al. 2003, pp. 876–78.

- ^ Nuclear Radiation and Health Effects 2015.

- ^ Beeman, Bellini & Cardani 2013.

- ^ Smirnov, Borisevich & Sulaberidze 2012, pp. 373–78.

- ^ Greenwood & Earnshaw 1998, p. 368.

- ^ Boltwood 1907, pp. 77–88.

- ^ Fiorini 2010, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Nosengo 2010.

- ^ Takahashi et al. 1987.

- ^ Thurmer, Williams & Reutt-Robey 2002, pp. 2033–35.

- ^ Tétreault, Sirois & Stamatopoulou 1998, pp. 17–32.

- ^ Thornton, Rautiu & Brush 2001, pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b c d Greenwood & Earnshaw 1998, p. 373.

- ^ Charles, Kopf & Toby 1966, pp. 1478–82.

- ^ Harbison, Bourgeois & Johnson 2015, p. 132.

- ^ a b Polyanskiy 1986, p. 20.

- ^ a b c Polyanskiy 1986, p. 32.

- ^ Wiberg, Wiberg & Holleman 2001, p. 914.

- ^ Polyanskiy 1986, p. 19.

- ^ a b Greenwood & Earnshaw 1998, p. 374.

- ^ Kaupp 2014, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Rappoport & Marek 2010, p. 509.

- ^ a b c Greenwood & Earnshaw 1998, p. 389.

- ^ Ensafi, Far & Meghdadi 2009, pp. 1069–75.

- ^ a b c King 1995, pp. 43–63.

- ^ Whitten, Gailey & David 1996, pp. 904–5.

- ^ Greenwood & Earnshaw 1998, p. 384.

- ^ Wiberg, Wiberg & Holleman 2001, p. 916.

- ^ Zuckerman & Hagen 1989, p. 426.

- ^ a b Greenwood & Earnshaw 1998, p. 382.

- ^ Greenwood & Earnshaw 1998, p. 388.

- ^ Bremholm, Hor & Cava 2011, pp. 38–41.

- ^ Silverman 1966, pp. 2067–69.

- ^ Greenwood & Earnshaw 1998, p. 398.

- ^ Macomber 1996, p. 230.

- ^ Yong, Hoffmann & Fässler 2006, pp. 4774–78.

- ^ Becker et al. 2008, pp. 9965–78.

- ^ Mosseri, Henglein & Janata 1990, pp. 2722–26.

- ^ Chia et al. 2013, pp. 6298–301.

- ^ Greenwood & Earnshaw 1998, p. 386.

- ^ Röhr.

- ^ Alsfasser 2007, pp. 261–63.

- ^ Greenwood & Earnshaw 1998, p. 393.

- ^ Stabenow, Saak & Weidenbruch 2003, pp. 2342.

- ^ a b c Polyanskiy 1986, p. 43.

- ^ a b c Greenwood & Earnshaw 1998, p. 404.

- ^ a b Wiberg, Wiberg & Holleman 2001, p. 918.

- ^ Polyanskiy 1986, p. 44.

- ^ Windholz 1976.

- ^ Zýka 1966, p. 569.

- ^ Greenwood & Earnshaw 1998, p. 405.

- ^ a b c d e Lodders 2003, pp. 1220–47.

- ^ Roederer et al. 2009, pp. 1963–80.

- ^ a b c Burbidge et al. 1957, p. 547.

- ^ Frebel 2015, pp. 114–15.

- ^ a b c Davidson et al. 2014, p. 4.

- ^ Emsley 2011, pp. 286, passim.

- ^ Cox 1997, p. 182.

- ^ a b c United States Geological Survey 2016.

- ^ Rieuwerts 2015, p. 225.

- ^ Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Kroonen 2013, *lauda-.

- ^ Nikolayev 2012.

- ^ Kroonen 2013, *bliwa- 2.

- ^ Kroonen 2013, *laidijan-.

- ^ a b c d Hong et al. 1994, pp. 1841–43.

- ^ a b Rich 1994, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f Winder 1993b.

- ^ a b Rich 1994, p. 5.

- ^ a b History of Cosmetics.

- ^ Yu & Yu 2004, p. 26.

- ^ Toronto museum explores 2003.

- ^ Bisson & Vogel 2000, p. 105.

- ^ Eschnauer & Stoeppler 1992, pp. 58.

- ^ de Callataÿ 2005, pp. 361–72.

- ^ Settle & Patterson 1980, pp. 1170.

- ^ Rich 1994, p. 6.

- ^ Thornton, Rautiu & Brush 2001, pp. 179–84.

- ^ Bisel & Bisel 2002, pp. 459–60.

- ^ Retief & Cilliers 2006, pp. 149–51.

- ^ Grout 2017.

- ^ Hodge 1981, pp. 486–91.

- ^ Gilfillan 1965, pp. 53–60.

- ^ Nriagu 1983, pp. 660–63.

- ^ Frankenburg 2014, p. 16.

- ^ Scarborough 1984, pp. 469–75.

- ^ Waldron 1985, pp. 107–08.

- ^ Reddy & Braun 2010, pp. 1052–55.

- ^ Delile et al. 2014, pp. 6594–99.

- ^ Finger 2006, p. 184.

- ^ Lewis.

- ^ Thornton, Rautiu & Brush 2001, p. 183.

- ^ Polyanskiy 1986, p. 8.

- ^ Thomson 1830, p. 74.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, surma.

- ^ Vasmer 1950, сурьма.

- ^ Kellett 2012, pp. 106–07.

- ^ a b Winder 1993a.

- ^ a b c Rich 1994, p. 7.

- ^ Cotnoir 2006, p. 35.

- ^ Samson 1885, p. 388.

- ^ Sinha et al. 1993.

- ^ Ramage 1980, p. 8.

- ^ Gray 2013.

- ^ Nakashima, Matsuno & Matsushita 2007, pp. 134–39.

- ^ Nakashima et al. 1998, pp. 55–60.

- ^ Ashikari 2003, pp. 55–79.

- ^ Beard 1995, pp. 66.

- ^ Australian Mining History.

- ^ Bisson & Vogel 2000, p. 85.

- ^ a b Bisson & Vogel 2000, pp. 131–32.

- ^ Lead mining.

- ^ Sohn.

- ^ Rich 1994, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d Riva et al. 2012, pp. 11–16.

- ^ Hernberg 2000, pp. 246.

- ^ Why use lead.

- ^ Markowitz & Rosner 2000, pp. 36–46.

- ^ Rich 1994, p. 117.

- ^ Rich 1994, p. 17.

- ^ Rich 1994, pp. 91–92.

- ^ United States Geological Survey 2005.

- ^ Zhang et al. 2012, pp. 2261–73.

- ^ Significant growth in 2014.

- ^ Guberman 2015.

- ^ Graedel 2010.

- ^ a b c Thornton, Rautiu & Brush 2001, p. 56.

- ^ a b Davidson et al. 2014, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Davidson et al. 2014, p. 17.

- ^ Thornton, Rautiu & Brush 2001, p. 51.

- ^ Davidson et al. 2014, p. 11.

- ^ Thornton, Rautiu & Brush 2001, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Primary Extraction.

- ^ Davidson et al. 2014, p. 25.

- ^ a b c d Primary Lead Refining.

- ^ Pauling 1947.

- ^ Davidson et al. 2014, p. 34.

- ^ a b Thornton, Rautiu & Brush 2001, pp. 52–53.

- ^ a b Thornton, Rautiu & Brush 2001, p. 57.

- ^ Street & Alexander 1998, p. 181.

- ^ Evans 1908, pp. 133–79.

- ^ Baird & Cann 2012, pp. 537–38, 543–47.

- ^ About Us 2010.

- ^ Bastasch 2015.

- ^ Parker 2005, pp. 194–95.

- ^ Krestovnikoff & Halls 2006, p. 70.

- ^ Street & Alexander 1998, p. 182.

- ^ Jensen 2013, p. 136.

- ^ How does lead absorb radiation.

- ^ Tuček, Carlsson & Wider 2006, p. 1590.

- ^ Copper Development Association.

- ^ Guruswamy 2000, p. 31.

- ^ Lansdown & Yule 1986, p. 240.

- ^ Audsley 1965, pp. 250–51.

- ^ Palmieri 2006, pp. 412–13.

- ^ Think Lead research.

- ^ Weatherings to Parapets.

- ^ Lead garden ornaments 2016.

- ^ Putnam 2003, p. 216.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey 2016, p. 97.

- ^ Progressive Dynamics, Inc.

- ^ State & Federal Energy.

- ^ Grid Services.

- ^ Leonard & Lynch 1958, pp. 414–16.

- ^ Burleson 2001, pp. 23.

- ^ Zweifel 2009, p. 438.

- ^ Wilkes et al. 2005, p. 106.

- ^ Randerson 2002.

- ^ Nriagu & Kim 2000, pp. 37–41.

- ^ Amstock 1997, pp. 116–19.

- ^ Rogalski 2010, pp. 485–541.

- ^ Emsley 2011, p. 280.

- ^ World Health Organization 2000, pp. 149–53.

- ^ Emsley 2011, p. 280, 621, 255.

- ^ a b Venugopal 2013, pp. 177–78.

- ^ Toxic Substances Portal.

- ^ U.S. Food and Drug Administration 2015, p. 41.

- ^ The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

- ^ Bergeson 2008, pp. 79–84.

- ^ a b Rudolph et al. 2003, p. 369.

- ^ Dart, Hurlbut & Boyer-Hassen 2004, p. 1426.

- ^ Kosnett 2006, p. 238.

- ^ Sokol 2005, p. 153.

- ^ Mycyk, Hryhorczuk & Amitai 2005, p. 462.

- ^ Liu & Liu 2015, pp. 1869–74.

- ^ Schoeters et al. 2008, pp. 168–75.

- ^ Casciani 2014.

- ^ Gottschlich 2001, p. 98.

- ^ Insel, Turner & Ross 2004, p. 499.

- ^ Berdanier, Dwyer & Heber 2016, p. 224.

- ^ Hunter 2008, pp. 15–18.

- ^ Prasad 2010, pp. 651–52.

- ^ Masters, Trevor & Katzung 2008, pp. 481–83.

- ^ Toxfaqs: CABS/Chemical Agent 2006.

- ^ Information for Community.

- ^ Moore 1977, pp. 109–15.

- ^ Tarragó 2012, p. 11.

- ^ Niosh Adult Blood.

- ^ Radiation Your Health 2015.

- ^ Tarragó 2012, p. 16.

- ^ Wani, Ara & Usman 2015, pp. 57, 58.

- ^ a b Trace element emission 2012.

- ^ United Nations Environment Programme 2010, pp. 11–33.

- ^ Smith & Flegal 1995, pp. 21–23.

- ^ Deltares & Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research 2016.

- ^ Grandjean 1978, pp. 303–21.

- ^ a b Levin et al. 2008, p. 1288.

- ^ Duda 1996, p. 242.

- ^ Marino et al. 1990, pp. 1183–85.

- ^ Schoch 1996, p. 111.

- ^ Regulatory Status of 2000.

- ^ Lead in Waste 2016.

- ^ Freeman 2012, pp. a20–a21.

- ^ Young 2012.

- ^ Bairagi et al. 2011, p. 756.

- ^ Park et al. 2011, pp. 162–74.

Bibliography

[edit]- Alsfasser, R. (2007). Moderne anorganische Chemie [Modern inorganic chemistry] (in German). Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-019060-1.

- Amstock, J. S. (1997). Handbook of Glass in Construction. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-001619-4.

- Anderson, J. (1869). "Malleability and ductility of metals". Scientific American. 21 (22): 341–43. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican11271869-341.

- Ashikari, M. (2003). "The memory of the women's white faces: Japaneseness and the ideal image of women". Japan Forum. 15: 55–79. doi:10.1080/0955580032000077739. S2CID 144510689.

- Audsley, G. A. (1965). The Art of Organ Building. Vol. 2. Courier. ISBN 978-0-486-21315-6.

- Australian Mining History Association. "Mining History". www.mininghistory.asn.au. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- Bairagi, H.; Khan, M.; Ray, L.; et al. (2011). "Adsorption profile of lead on Aspergillus versicolor: A mechanistic probing". Journal of Hazardous Materials. 186 (1): 756–64. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.11.064. PMID 21159429.

- Baird, C.; Cann, N. (2012). Environmental Chemistry (5th ed.). W. H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 978-1-4292-7704-4.

- Bastasch, M. (2015). "California officially bans hunters from using lead bullets". The Daily Caller. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- Beard, M. E. (1995). Lead in Paint, Soil, and Dust: Health Risks, Exposure Studies, Control Measures, Measurement Methods, and Quality Assurance. ASTM International. ISBN 978-0-8031-1884-3.

- Becker, M.; Förster, C.; Franzen, C.; et al. (2008). "Persistent radicals of trivalent tin and lead". Inorganic Chemistry. 47 (21): 9965–78. doi:10.1021/ic801198p. PMID 18823115.

- Beeman, J. W.; Bellini, F.; Cardani, L.; et al. (2013). "New experimental limits on the α decays of lead isotopes". The European Physical Journal A. Vol. 49, no. 50. doi:10.1140/epja/i2013-13050-7. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- Berdanier, C. D.; Dwyer, J. T.; Heber, D. (2016). Handbook of Nutrition and Food (3rd ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4665-0572-8. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- Bergeson, Lynn L. (2008). "The proposed lead NAAQS: Is consideration of cost in the clean air act's future?". Environmental Quality Management. 18: 79–84. doi:10.1002/tqem.20197.

- Bisel, S. C.; Bisel, J. F. (2002). "Health and nutrition at Herculaneum". In Jashemski, W. F.; Meyer, F. G. (eds.). The Natural History of Pompeii. Cambridge University. pp. 451–75. ISBN 978-0-521-80054-9.

- Bisson, M. S.; Vogel, J. O. (2000). Ancient African Metallurgy: The Sociocultural Context. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-0261-1.