Youngest son

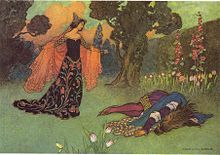

The youngest son is a stock character in fairy tales, where he features as the hero. He is usually the third son, but sometimes there are more brothers, and sometimes he has only one; usually, they have no sisters.

In a family of many daughters, the youngest daughter may be an equivalent figure.[1]

Traits

[edit]Prior to his adventures, he is often despised as weak and foolish by his brothers or father, or both — sometimes with reason, some youngest sons actually being foolish, and others being lazy and prone to sitting about the ashes doing nothing. But some times the youngest son is the one that does the most work.[2] Sometimes, as in Esben and the Witch, they scorn him as small and weak.

Even when not scorned as small and weak, the youngest son is seldom distinguished by great strength, agility, speed, or other physical powers.[3] He may be particularly clever, as in Hop o' My Thumb, or fearless, as in The Story of the Youth Who Went Forth to Learn What Fear Was, but more commonly his traits include refusal to abandon the quest, as in Tsarevitch Ivan, the Fire Bird and the Gray Wolf or The Brown Bear of the Green Glen, and courtesy to strangers, especially those who appear weak, as in The Water of Life or The Fool of the World and the Flying Ship.[4]

Plots

[edit]He generally succeeds in tasks after his older brothers have failed, as in The Red Ettin, or all three are set to tasks and he is the only one to succeed, as in Puddocky. He may happen on the donor that gives him his success, as Puddocky has pity on him, but usually he is tested in some manner that distinguishes him from his brothers: in The Red Ettin he is offered the choice of half a loaf with his mother's blessing and the whole with her curse, and takes the blessing where his brothers took the curse, and in The Golden Bird he takes a talking fox's advice to avoid an inn where his brothers decided to abandon their quest.

This magical helper is often long faithful to him; he may fail many times after the initial test, often by not respecting the helper's advice. Indeed, in The Golden Bird, the fox declares that the hero does not deserve his help after his disobedience, but still aids him.[5]

This success may make his brothers an additional obstacle, as in The Golden Bird, where they overpower him and steal what he has won on his quest. In some tales, such as The Grateful Beasts, they conclude he may be a rival in advance, and they attempt to stop him before the quest; in others, such as Thirteenth or Boots and the Troll, he must set to tasks because they have spitefully claimed that he said he could.

This rivalry is not a necessary component of the character. He may also be the only one of the brothers to set about the work, as in Dapplegrim. In some tales, such as the Norwegian version of The Master Thief, the brothers are only mentioned and vanish from the tale entirely when they set out to seek their fortune.

Youngest daughters

[edit]

Heroines in fairy tales are more often marked out as stepdaughters, but sometimes they appear as the youngest daughter. In Molly Whuppie, it is the youngest who outwits the ogre. The White Bear in East of the Sun and West of the Moon marries the youngest daughter; in the Black Bull of Norroway, the heroine's older sisters set out to seek their fortunes before her. She may be the only one willing to fulfill a promise that their father made, as in Beauty and the Beast or Bearskin. In The Little Mermaid, it is the youngest daughter of King Triton who falls in love with the prince after she saves him from drowning. In Diamonds and Toads, the younger-&-least favoured daughter of a widow marries a king's son (after having passed a 'Test of Character' administered by a fairy in disguise).

Sibling rivalry may also spring up in these stories, but usually over the youngest daughter's marriage. They may incite their sister to break the taboo her husband has laid on her, as in Cupid and Psyche, or make it appear that she has killed her own children to make her husband hate her, as in The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird.

Youngest daughters may also appear as not the heroine of the tale, but the bride of the hero; when there is more than one princess, the bride is almost always the youngest, as in King Kojata, The Hairy Man, The Magician's Horse, or Shortshanks. A ballad may feature three sisters solely so that the youngest of them can be preferred.[6] The choice of a younger and prettier sister may also cause intrafamily friction in a ballad.[7] The Twelve Dancing Princesses is a subversion; in most versions the hero chooses to wed the eldest princess while the youngest of the twelve daughters was the only one to realize she and her sisters were being followed during their nightly ventures.

Sibling pairs

[edit]

A pair of siblings, whether a girl and a boy as in Hansel and Gretel or two girls as in Snow-White and Rose-Red or Kate Crackernuts, or two boys as in The Gold-Children, often features them as co-protagonists rather than as rivals. This is, in fact, the more common pattern when the children are of the opposite sex, or when they are boys (usually twin boys).[8]

The story of the "kind and unkind girls" often features a pair as rivals.[9] They are more often stepsiblings than siblings, but as siblings, the younger is generally the favored, as in Diamonds and Toads or some variants of The Red Ettin.

Brothers with a sister

[edit]In tales where the brothers had a sister, she is usually the heroine of the tale, as in The Seven Ravens, The Dancing Water, the Singing Apple, and the Speaking Bird (in the second generation), The Fair Fiorita, The Death of Koschei the Deathless, The Twelve Wild Ducks or The Blue Bird. Even in these tales, the youngest son may be set out: in The Seven Ravens, he is the first to guess that their sister has found them; in The Twelve Wild Ducks, he argues against his oldest brother, who wants to kill their sister as the cause of their misery.

Sibling rivalry in fairy tales is, in general, a trait of same-sex siblings.[8]

Modern variants

[edit]The ubiquity of this theme has made it an obvious target for revisionist fairytale fantasy. Andrew Lang has his Prince Prigio jeer at the notion that he should go first on the quest, when he is the oldest son; only after his two younger brothers have not returned can he be compelled to go. Likewise, in Diana Wynne Jones's Howl's Moving Castle, Sophie, being the oldest daughter, is resigned to having the worst chances to make her fortune, but is precipitated into the plot by evil magic.

Fairy tales

[edit]Tales that feature youngest sons:

- Baš Čelik

- The Crystal Ball

- Don Joseph Pear

- The Frog Princess

- The Giant Who Had No Heart in His Body

- The Grateful Beasts

- Ibong Adarna

- Laughing Eye and Weeping Eye

- Lord Peter

- The Nine Peahens and the Golden Apples

- The Princess on the Glass Hill

- The Queen Bee

- The Water of Life

- The Singing Bone

- Thirteenth

- Prince Ivan and the Grey Wolf

Tales that feature youngest daughters:

- The Battle of the Birds

- Bearskin

- Beauty and the Beast

- The Brown Bear of Norway

- Finette Cendron

- Fitcher's Bird

- The Goose-Girl at the Well

- How the Devil Married Three Sisters

- The Hut in the Forest

- The Little Mermaid

- Molly Whuppie

- The Tale of Tsar Saltan

- The Twelve Dancing Princesses

- Water and Salt

See also

[edit]- Seventh son of a seventh son

- Reluctant hero

- King David

- Haakon the Good

- The Tale of the Three Brothers (Harry Potter)

References

[edit]- ^ Heidi Anne Heiner, "Annotations for East of the Sun & West of the Moon"

- ^ Maria Tatar, The Hard Facts of the Grimms' Fairy Tales, p87, ISBN 0-691-06722-8

- ^ W. H. Auden, "The Quest Hero", Understanding the Lord of the Rings: The Best of Tolkien Criticism, p37 ISBN 0-618-42253-6

- ^ Maria Tatar, The Hard Facts of the Grimms' Fairy Tales, p89, ISBN 0-691-06722-8

- ^ Maria Tatar, p 264, The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales, ISBN 0-393-05163-3

- ^ Francis James Child, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads, v 1, p 142, Dover Publications, New York 1965

- ^ Barbara A. Hanawalt, The Ties That Bound: Peasant Families in Medieval England p191 ISBN 0-19-504564-5

- ^ a b Maria Tatar, Off with Their Heads! p. 68 ISBN 0-691-06943-3

- ^ Maria Tatar, p 341, The Annotated Classic Fairy Tales, ISBN 0-393-05163-3